Geography, not Socio-Demographics: Explaining the

PDS (Party of Democratic Socialism) Vote in Berlin

John

O’Loughlin

Frank

Witmer

Valerie

Ledwith

*

John O’Loughlin is Professor of Geography in the Institute of Behavioral

Science University of Colorado Boulder Frank

Witmer is a PhD student in the Department of Geography

and in the Institute of Behavioral

Science University of Colorado Boulder Valerie

Ledwith is a PhD student in the Department of Geography, University of California Los

Angeles Ron Johnston of the

University of Bristol (UK) for providing us with the EMax entropy maximizing

program. Tom Dickinson and Clionadh

Raleigh helped us with the preparation of the paper.

ABSTRACT

The PDS (Partei

Demokratische Sozialismus – Party of

Democratic Socialism) continues to gain electoral support in the pos-unification elections

in the former German Democratic Republic (

_____________________________________________________________________________________

The process of the unification of Germany Berlin Berlin Germany Hesse ), the governing

coalitions of Länder are seen as

tests of how well parties can cooperate and as predictors of a possible federal

government coalition. But, though the

Berlin SPD-PDS coalition governs the entire city-state, the geographic bases of

support of the coalition partners are clearly divided into two halves along the

line of the former Berlin Wall. The

German capital, though politically united, still shows a powerful wedge between

the two parts – “die Mauer in den Köpfen” (the wall in people’s heads) - as

seen in electoral statistics and public opinion polls.

In this

paper, we examine the PDS support in two recent elections, those for the Landtag (state parliament) in 1999 and

2001 using detailed data for the electoral districts of Berlin East Berlin , the

availability of a large representative sample allows a matching of survey and

aggregate data to probe the geographic contexts of the votes. We ask if the PDS support from specific

groups (e.g., the ratio of people over 60 who choose the party) varied

according the overall trends or if there are special circumstances that can

account for the relative success in certain districts. Though the survey sample was large (a sample

of 15,936 in 1999), the respondents are not adequately distributed across all

78 electoral districts (Wahlkreise)

to allow analysis by district. Instead,

we must infer the district-level estimates using aggregate data. Recent developments in ecological inference

enable such inferences and in this paper, we compare the results from EzI

(Ecological Inference – King, 1997) and EMax (entropy maximizing – Johnston and

Pattie, 2000). While the results are

similar, the results presented in this paper offer another check on the

consistency of the two methods and an evaluation of the comparative advantages

of each. The district estimates are then

used to gain insights into the variation of the kinds of support of the PDS

across socio-demographic groups.

The

growing electoral successes of the PDS in

The October 21, 2001

Table 1. Percent Vote by Party

Table 2. Percent Vote for PDS

Berlin

The ideological divisions that had

permeated post-war politics in the city were made chillingly clear with the

construction of the Berlin Wall in August 1961 (Zimmer, 1997; Elkins and

Hofmeister, 1988). Although an armed

boundary between East and

In hindsight,

the reunification of

On

Former

German Chancellor Willy Brandt's famous prediction, as the Berlin Wall fell,

that “what belongs together will now grow together” (quoted in Leiby, 1999,

109) shows the degree of political naivéte that permeated

Direct federal subsidies to

The German electoral system has been

termed a “personalized proportional law”, with half of the parliamentary

deputies elected by a plurality vote in single member districts (Erststimmen) and half by proportional

representation from land lists (Zweistimmen)

(Conradt, 1996, 155). The first vote is

given to individual candidates, while the second is a party vote. The second (party) vote is usually deemed

most important because it is used to determine the final percentage of

parliamentary mandates a party will receive.

In order to ensure equal proportionality, the number of seats won in the

district elections are deducted from this total; thus the more district mandates

(first votes) a party wins, the fewer party (second vote) seats it will

receive. This electoral process can lead to a situation where there will be

more district votes (candidates) than the parliamentary mandate a party

receives through proportional representation (Edwards, 1998). This is known as

the Überhangmandate (excess mandate), and was an important

electoral loophole in the party strategy of the PDS in the federal elections of

1994 and 1998. In addition to its

personalized proportional law and its two vote system, the

The PDS: The

Regional-Alternative Party

Since the reunification of

The

purpose of this paper is to understand why the PDS as a post-Communist

political party continues to hold such strong regional appeal and to evaluate

the possible diffusion of its support. Among

the multiple explanations proffered, a key idea equates the success of the PDS

with its appeal as a regionalist-protest party.

Its success has surprised many

political commentators, who had assumed that it would not outlive the immediate

post-unification period in

Unlike many other former Communist

parties, the PDS confronted the challenge in 1990 of being immediately inserted

as a marginal actor into an externally directed, fully established functioning

political system (Phillips, 1999). While

the founding elections around 1990 were largely electoral disasters for

ex-Communist parties, the PDS made it to the Bundestag, by utilizing the

constitutional loophole afforded by the Überhangmandate.

This electoral success is even more

impressive since the party received no funding from the West German government

prior to the election. In contrast, all

three establishment West German parties, (CDU, SPD and FDP) contributed direct

financial support to their Eastern counterparts (Neugebauer and Stöss,

1996). The PDS consolidated their

success in the second round of national elections in 1994 by gaining a total of

30 seats. This reflects their continued

use of the Überhangmandate, but also

an increase of 2.4% of the national vote from 1990 to 4.4% (Kleinfeld,

1995). This was seen as strengthening

the party’s role as a reformed party and as further proof that they were a

resilient political force (Ziblatt, 1998).

This resilience is further confirmed by the party’s performance in the

1998 Federal election. For the first

time in its history, it cleared the electoral hurdle by polling 5.1% in the

Federal Republic as a whole (McKay, 2000).

The consolidation of the PDS as a

legitimate political party is not uniformly accepted by the German political

establishment, despite a growing academic consensus that ex-Communist parties

can have a stabilizing influence in the transition to a consolidated democracy. Post-Communist successor parties can

re-socialize an otherwise excluded and alienated segment of the electorate and

enable a more responsive party system (Mahr and Nagle 1995; Higley et al.,

1996). McKay (2000), however, asserts

that the persistence of an elite from Communist times threatens democratic

processes because these cadres are not interested in reform, but rather in

consolidating their elite position. Waller (1995) believes that the

organizational skills and resources of ex-Communist parties give them a

political advantage that is not necessarily democratic. Morueau (1998, 283) is

even harsher in his assessment of the PDS, defining them as a leftwing

extremist, anti-system party that promotes societal change through radical

democratization as camouflage. This view

is also the one most often taken by the centrist CDU party in Germany, who view

the historical ties of the PDS to the SED as good reason to isolate them from

mainstream politics (McKay, 2000).

Indeed, the CDU wants to put the PDS under the surveillance of the Verfassungschutz,

the agency in charge of protecting the constitution (Patton, 2000).

Ishiyama (1999c) takes an optimistic

view of the PDS, viewing “electoral demand” - issues relating to economic

conditions, traditional identities, uncertainty caused by transitions and the

related nostalgia for the Communist era - as important in explaining the

success of former Communist parties.

Ishiyama (1999b) makes further distinction between a successor party and

an adaptive party. The former claims

their successor status and retains members from the old Communist party, while

adaptive parties repudiate their Communist ideology and accept democratic

norms. It is clear that the PDS falls into the adaptive category more clearly

than the successor camp. Its critics

argue the impossibility of this, given the continued role of former SED members

in the PDS and the continued presence of a hard-line Stalinist faction (Patton,

2000). The SED had tried to position

itself on the left of the political spectrum as a contrast to the Kohl

government coalition. It soon realized

that this electoral strategy would not ensure its survival, due in a large part

to plummeting support and internal disagreements about the direction the party

should take (Barker, 1998; Hough, 2000b).

By June 1990, the SED membership of 2.8 million in 1989 had plummeted to

350,000 members (Kleinfeld, 1999).

Recent membership figures of the PDS estimate the figure is

approximately 100,000, or less than 5% of the SED membership before the end of

East Germany (Kleinfeld, 1999). This

trend is also true in East Berlin.

Unlike its electoral support, membership has consistently declined

during the 1990’s. In March 1991, the

PDS had over 42,000 members in Berlin but by the end of 1998, membership stood

at under 17,000 (McKay, 2000).

The Electorate of the PDS

A dramatic contrast in age profile exists between the membership of

the PDS and those who support the party in elections. PDS members tend to be over 50 years of age

and overwhelmingly former SED members.

PDS voters in former East Germany, on the other hand, tend to be

younger; about 25% of voters between the ages of 18 and 24 voted for the PDS in

the 1994 Bundestag election(Krisch, 1996).

Despite an increasingly ageing membership, the party has been able to

register support equally from across all age categories, with the over 60 age

group being slightly the weakest (Hough, 2000a). This age distribution is important in terms

of the survival and future growth of the PDS as a small party within the German

electoral system. As party membership

ages, the appeal of the party to younger voters is extremely important for

ensuring the reproduction of its support (Kleinfeld, 1995). However, this is not a simple undertaking. In the Eastern Länder in general, party

membership appears to have little appeal for young people and the moderate

parties in particular look decidedly middle-aged (McKay, 2000). It is here that the historical ties of the

party may enable its continued success in the East. The PDS funds 23 Arbeitgemeinsaften (AGs: workgroups), to deal with different

interest groups within their constituencies.

These local level organizations within the party, a throwback to the

importance of party-organized civil society in the GDR, are run independently

from the party’s central structure (McFalls, 1998; Kleinfeld, 1995; Brie,

1995). It seems plausible that this

strategy can play a dual role of

attracting new members and voters for the party, and consolidating the party’s

objective of nurturing a more

‘bottom-up’ approach to democracy (Neugebauer and Stöss, 1996; Ziblatt,

1998).

Unemployment was

the most important issue motivating voters to choose the PDS in the 1994

elections (Dalton and Bürklin 1996, Gibowski 1995, Krisch, 1996). Support for

the party continues to be strongest in the outer areas of East Berlin where the

economic benefits of the redevelopment of the old city center and the transfer

to the federal seat of government from Bonn to Berlin have not yet created new

employment opportunities. The PDS cannot

be defined as merely the party of the unemployed; in fact, the PDS is certainly

not exclusively a working-class party, nor does it appeal only to those on the

lower rungs of the social ladder. It

attracts intellectuals and individuals with above-average interest in politics

(McKay, 2000). In effect, the PDS is

becoming the party of those employed who are concerned about unemployment, a

new worry for citizens of the former East Germany. As such, the party also benefits from Ostalgie, or East German memories of the

good elements of life in the former German Democratic Republic, among which was

guaranteed employment (Roth, 1999; Wiesentha, 1997; Zelle, 1998).

Three

sets of explanations are usually suggested to explain the post-1990 electoral

success of the PDS. First, the PDS vote

is characterized as “catch-all” in nature, made up of support of government

officials, civil servants, university students, workers and the unemployed of

the former GDR. The appeal of the PDS to

university-educated voters also holds true in the West, where the PDS did best

in districts with a high percentage of the population with a University or Hauptschule qualification, and a lower percentage of

technical school graduates (Gibowski, 1995).

In general, the Eastern electorate is more secular and liberal on social

issues (Roesler, 1998; Krisch, 1996; Dalton and Bürklin, 1996; Schmitt, 1995;

Kleinfeld, 1995;Gibowski, 1995; Bauer-Kaase, 1994; Rattinger, 1994). As a “catch-all protest party,” the PDS poses

a challenge to the Western political system by representing dissatisfaction and

frustration with the liberal democratic norms shaping contemporary German

society (Strom and Mayer, 1998; Oswald, 1996; Roesler, 1998). Established Western parties such as the CDU,

who initially had the support of many GDR citizens, are no longer seen as

legitimate representatives serving the needs of the Eastern electorate. Protest voting is not the expression of a

wish to return to the GDR, but rather an expression of distaste with the harsh

realities and uncertainties of capitalist life (Hough, 2000b).

The national

election of 1998 set a historic precedent since it was the first time in

Germany’s history that five parties achieved more than 5% of the Zweistimmen

and entered the Bundestag. In the

campaign, the CDU helped to determine the protest vote niche for the PDS by not

only ignoring the geographical dimension to contemporary German politics, but

further polarized the electorate by attempting to link the PDS with the

negative aspects of Berlin’s history such as the building of the Wall (McKay, 2000). The CDU strategy was to mobilize the more

conservative voters to vote against the PDS in the belief that a higher voter

turnout would weaken the PDS (Krisch, 1996; Dalton and Bürklin, 1996;

Kleinfeld, 1995). Instead, the 1998

election demonstrated a solid and expanding appeal of the PDS to the Eastern

electorate, reaching 19.5% (Rattinger and Kraemer, 1998). To sweeten the victory, the PDS breakthrough

came in a year of the highest voter turnout (82%) since unification (Phillips,

1999).

Since

unification, the PDS has seen its support in regional elections in the five

Eastern states go steadily upward, highlighting the electoral disunity of the

country. A second explanation for the

PDS success, political culture, claims that forty years of Communist rule led

to different social and cultural norms in the former Eastern state. The socialization process under the Communist

regime created a different political culture because, within East Germany,

national ideology and identity were closely bound with Communist principles of

egalitarianism and a working class culture (Segert, 1998; Mushaben, 1997;

Langguth, 1995). Citizens of the former

GDR are now searching for a new German identity, having been socialized in that

part of Germany where identities were framed in anti-West German sentiment.

Howard (1995) argues that East Germans constitute a separate ethnic group,

characterized as a self-perpetuating and territorially bounded group, with a

shared historical identity and political representation (i.e. the PDS). The identity is often typified by Ostalgie, where the past is increasingly

romanticized by Easterners as a critique of the Other, West Germans. Segert

(1998) characterstic this Ostalgie as

“problematic normalization”, where one’s sense of identity is tied to a deviant

sense of Other in order to

rationalize the former Eastern identity.

The utilization

of regional rhetoric gained a firm foothold in the party ideology of the PDS by

1994, centered on the idea that the mainstream West German parties were

ignoring East German ‘interests’.

Reflecting widespread East German dissatisfaction with the process of German

reunification, it also asserted that the PDS stands as the most authentic

representative for East Germans as a regionally distinct culture (Ziblatt,

1998). The PDS used a blend of charisma, personified in its leader Gregor Gysi,

and language, that emphasized territorial identity, shared regional history and

the social, cultural and economic differences that exist between East and West

Germany to appeal to an increasing number of alienated Eastern voters. Importantly, the PDS had more organizational resilience

than a typical protest party and its electoral tactics involved more than

assuming the mantle of an Eastern protectorate.

Preceding the 1990 Bundestag

election, the constitutional court ruled that the 5% threshold should apply

separately to East and West Germany. In

response, the PDS focused its campaign solely on the Eastern region, resulting

in seventeen PDS representatives in the united German Parliament (Ziblatt,

1998, 18). In 1994, thirty delegates were sent to the Bundestag in Bonn, though the PDS got only 4 per cent of the vote

but up to 40 per cent of the vote in some Eastern Berlin districts and 20 per

cent in Eastern Germany overall (Ziblatt, 1998). In addition, it highlighted the fact that the

PDS had established itself as the third strongest party in Eastern Germany

(Wittich, 1995).

Prior to the self-identification of

PDS party leaders as regional guardians of East German interests (McFalls,

1998), the party was overtly concerned with the notion of “renewed socialism”

(Ziblatt 1998). The PDS adoption of its

role as defender of Eastern interests had its roots in a “grassroots”

organization called “the committee for social justice,” of which the PDS

chairman Gregor Gysi was a cofounder. As

this “committee” lost its political relevance in the years between 1990 and

1994, many of its ideas were co-opted by the PDS to ensure their appeal to the

Eastern electorate (Lang et al., 1995).

Furthermore, it was only eight months before the 1994 Federal election

when "Eastern interests"

became the rallying call of the PDS leadership.

In effect, the public shift of attitude towards viewing the unification

process as colonization (or Kohl-inization,

after the former German Chancellor

Helmut Kohl) by the Wessies

and the Treuhandshalt (the

privatization organization that sold off East German state assets) molded the

party’s new role and purpose as a regional defender by its perceived harsh

actions (Ziblatt, 1998).

Since the 1998 federal election,

there has been a further shift in the self-definition of the PDS as a regional

party. The official party line now

claims that they are a legitimate social-democratic party that will appeal to

the entire German electorate. However,

their electoral adversaries continue to pigeonhole the PDS as a party with

questionable roots, not at all interested in embracing the ideals of the

West. However, it is exactly this type

of attitude that is seen in the East as Western chauvinism and will continue to

define the PDS as the only party able and willing to represent the eastern

electorate. By continuing to serve a

sizeable group of people within an imperfect democratic system, the PDS is an

alternative to voters who would either abstain or support more radical and

politically-questionable right-wing parties.

The PDS will continue to offer a crucial stabilizing and integrating

factor in the East (Ertman, 2000).

A third possible

explanation for the role of the PDS is dissatisfaction with the democratic

system of government that is increasingly linked to economic performance in

post-Communist societies (Bauer-Kaase, 1994).

This connection is also seen in East Germany, especially because East

Germans place far more importance on social policy and social justice than do

West Germans (Eith, 2000). The syndrome

of post- unification dissatisfaction for many East Germans resulted from

adjustments to the social, economic and cultural challenges of West

Germany. Overall, East Germans have

experienced an increase in affluence, highlighted by rises in income,

retirement pensions and access to goods and services (Segert, 1998). However, income levels in Eastern Germany are

still only 73% of those in the West and pensions are approximately four-fifths

of a typical West German pension.

Economic restructuring has led to a complete transformation of the job

Kitschelt’s “winners–losers” hypothesis

(1992, 1994, 1995) holds that individuals in the former Communist East pay

close attention to their personal economic situation when deciding about their

vote (See also O’Loughlin et al., 1997 and Rattinger and Kramer,

1998). According to Kitschelt, voting

choice in post-Communist societies is driven by prospective and egotistic

considerations, while in consolidated democracies, there is a greater level of

retrospective voting. Increasing

economic development and affluence in former Communist countries induces a

general shift of voter preferences toward libertarian, participatory systems. These claims were initially validated by the

general acceptance in the former GDR of the liberal democratic model in

Germany’s first national election of 1990.

However, when the expectations did not match reality, a retrenchment

towards traditional values and disillusionment with the liberal economic system

of West Germany led to an increase in support for the PDS. The PDS appealed to the losers of

A

related hypothesis to the “winners-losers” model focuses upon the importance of

system performance in determining voter choice; in the East, voters take a more

pragmatic approach to democracy, judging it in terms of the comparative

performance of a socialist system (Conradt, 1997). Citizens expect to convert their individual

resources into economic benefits in the

Prior

to the 1994 national German elections, 84% of PDS supporters felt more like GDR

citizens than Germans (Neugebauer and Stöss, 1996). While this can overlap with the idea of

economic losers of unification, it could also be that there are distinct

strands of support within the PDS support base, one based on the loss of

identity, the other on economic loss.

From this perspective, the appeal of the PDS is not merely to the “old

guard” who are nostalgic for Communism, but equally its defense of the old way

of life that offers some stability to those most affected by the complexities

of post-unification society. This

approach allows conceptual space for both the regional and protest aspects of

the PDS party, which cannot be treated as clearly separate definitions. It also offers an explanation of the

geographic differences that exist not only between East and West; but also

within the East itself.

Data and Methods

Berlin was divided

into 23 Bezirke (districts) until the municipal reform of 2000 that

combined some of the smaller districts.

Each of the Bezirke has its own council and though the Berlin

Wall is now removed, its line

Figure 1 - Locations of the 23 Bezirke (districts) of Berlin prior to the redistricting in 2000

that reduced the number to 12 by combining Friedrichshain and Kreuzberg;

Charlottenburg and Wilmersdorf; Steglitz and Zehlendorf; Tempelhof and

Schöneberg; Treptow and Köpenick; Marzahn and Zellersdorf; Mitte, Tiergarten and Wedding; Hohenschönhausen and Lichtenberg; Pankow,

Prenzlauer Berg and Weißensee while Spandau, Neukölln and Reinickendorf

remained as single districts.

The 23 Bezirke

are divided into 78 Wahlkreise (electoral regions) and the results for

these regions provided the basic data for this paper. We concentrate on the party vote (Zweistimmen)

rather than the candidate races in the individual 78 regions. As can be seen from Table 1, these two vote

percentages are typically very close and though some candidates, like the party

leaders, receive a personal vote in excess of the usual party support in a

region, the second vote is a better representative index of party

preferences. The second major data

source for the paper consists of demographic data for the electoral regions but

unfortunately, these data are only available for age and gender

categories. The third source consists of

a large mail survey (a total of 15936

respondents) at the time of the 1999 election from which we generate regional

level estimates of the support of age and gender groups for the PDS (Bömmerman,

1999).

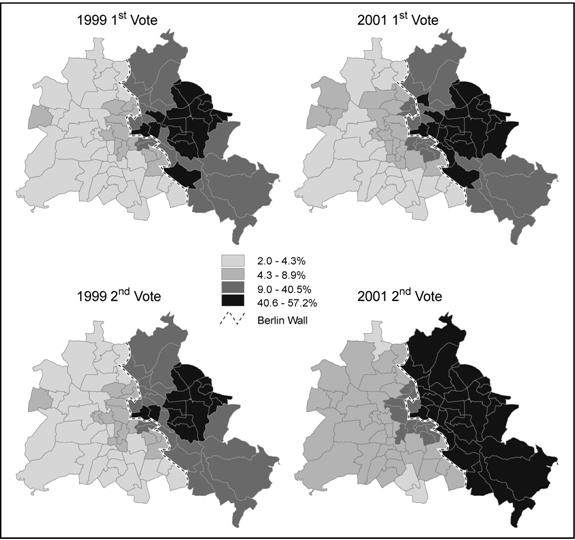

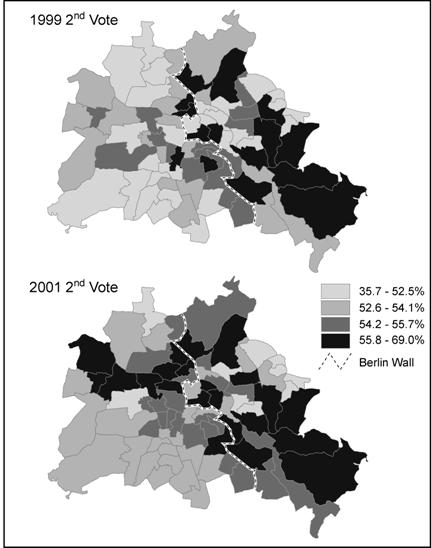

A comparison of the distribution of

the PDS first and second votes in 1999 and 2001 in the four maps in Figure 2

shows both strong correlations and a diffusion of the PDS zone of

dominance. The biggest difference in the

maps is the relative size of the regions of the two votes. In 1999, the number of Wahlkreise with

over 40.6% support for the PDS was similar for the first and second votes; by

2001, the number of Wahlkreise with more than 40.6% for the PDS second

(party) vote was dramatically larger than the first vote, though both showed

gains over 1999. These trends, though

only for a two year period, match wider developments in the PDS diffusion. Early successes came in the form of

individual candidates winning in the single-member constituencies (first

votes). Over time, the party as a whole

is gaining new adherents, while continuing to maintain their individual seats

and even increase them. In the 2001

second vote distribution, the PDS gained more than 40.6% in every one of the 32

Wahlkreise in former East Berlin and won a further 20-30% of the vote in

the older, central districts of the unified capital, the heartland of the Green

party support in the 1990s (Doud, 1995; Lawson, 1998; Ledwith, 2000). More general comparison of the four maps

shows a classic diffusion pattern; the key question after 2001 is whether the

PDS can continue to spread their success to the traditional SPD areas of

working-class West Berlin and thus becoming a city-wide party like their SPD

coalition partners.

To estimate the composition of the

PDS vote across the 78 Wahlkreise, we turned to two procedures that have

been developed to infer individual voter behavior from aggregate statistics and

which can generate small area estimates for the variables of interest. While the voter exit polls are valuable in

providing “global”

or city-wide values

(e.g., the percentage of women who voted for the PDS), these are not available

in a reliable manner for the individual Wahlkreise. Survey data have only been published for the

1999 election, the focus of the remainder of this paper. A total of 116,646 voters were sent a mail

survey questionnaire in 124 Stimmbezirke

(electoral precincts) across Berlin for a sample of 4.77%. This poll was re

Figure 2 - Distribution of the First and Second Votes for the PDS in the Berlin

Landtag elections of 1999 and 2001 by the 78 Wahlkreise (election districts).

indicated by the

close fit of the polling data and the actual numbers. For example, survey results indicated that

38% of East Berliners voted for the PDS (the actual proportion was 40%) and the

respective values for West Berlin were 4.5% and 4.4% (Bömermann, 2001). Since the EMax method used for small-area

estimates uses the global survey data, it is imperative that these values stand

as an accurate reflection of the electoral preferences.

The first procedure used to generate

the Wahlkreis estimates is the

ecological inference model from King (1997).

EzI (ecological inference) has been widely used in political science to

estimate vote-splitting, racial bloc-voting, and electoral choices for

socio-demographic groups. In geography,

the procedure offers great prospects for revitalizing the discipline of electoral

geography to allow individual-aggregate analyses and it has been the subject of

favorable review by geographers (Johnston, 1998; Fotheringham, 2000;

Davies-Withers, 2001) and used to understand the variation of the vote in

Weimar Germany (O’Loughlin, 2000, 2002) and Ukraine (O’Loughlin, 2001). Because of this growing familiarity, the method is only briefly

summarized here – further details are available in King (1997).

In

order to calculate the PDS support in Berlin among older voters (aged 60 and

over), we use the proportion of the population over 60 (Xi) and the

PDS percentage (Ti) for each geographic unit, in this case, the 78 Wahlkreise geographic units of Berlin in 1999. Using King’s notation, in the current

example, the independent variable, X, is the aged 60 population and the

dependent variable is PDS support, T. An

identity is used for combinations of the district values for Ti (PDS)

and Xi (over 60), Ti = bib

Xi + biw

(1 – Xi). The purpose of the

EzI modeling is to estimate βb (the aggregate rate of the PDS

vote among the over 60 population for the whole city) as well as the estimates

for the individual Wahlkreise (78 units in all), bib. Combined with information about the bounds

for each district, found by projecting the regression line onto the horizontal

(bib

, the PDS vote) and the vertical (biw,

the non-PDS vote) axes, the EzI method combines two earlier inference methods

(King, 1997; see also Figure 4 in this paper).

When the bounds on the axes are narrow, the stronger are the chances of

a plausible and accurate solution.

Reliable estimates for the turnout rate of Kuchma voters in Ukraine were

presented by O’Loughlin (2001) using this methodology.

The second procedure, termed EMax,

differs from King’s in two main ways (Johnston and Pattie, 2000). First, EMax uses the mathematical

entropy-maximizing approach rather than a statistical approach. Second, EMax

requires additional data that describe global patterns to constrain the

estimates further. These additional data

are usually obtained from sample surveys.

This latter requirement means, in effect, that EMax can be used in fewer

circumstances then EzI since public opinion surveys became commonplace only in

the past half-century. Historical

studies, such as the composition of the support for the 1930s Nazi party, must

rely on EzI for estimates (O’Loughlin, 2002).

The entropy-maximizing procedure produces maximum-likelihood estimates

given a set of initial constraints. The

EMax procedure is best explained by example.

For a fictional district of Berlin with 9 voters, consider the

following gender and PDS vote row and column sum constraints:

|

|

PDS |

not PDS |

|

|

Female |

? |

? |

5 |

|

Male |

? |

? |

4 |

|

|

3 |

6 |

|

In this example, we are interested in

finding the most likely allocation of votes for the PDS, which requires

calculating the value of each cell denoted by the question

The EMax

procedure starts from the macrostate and calculates all possible values for

each question

|

|

PDS |

not

PDS |

PDS |

not

PDS |

PDS |

not

PDS |

PDS |

not

PDS |

|

Female |

0 |

5 |

1 |

4 |

2 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

|

Male |

3 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

4 |

Since these four combinations are the

only possible solutions that satisfy the given constraints, one of them must

reflect the actual breakdown of votes for this district. EMax selects the mesostate based on the

number of associated microstates, where each microstate represents a

different distribution of voters. For

instance, in the first mesostate, the five female voters can only be allocated

one way: all voted for a party other than the PDS. Each one of the four males, however, could

have voted for a non-PDS party.

Therefore, there are a total of four microstates associated with the

first mesostate. For the second

mesostate, any of the five females could have cast the one vote for the PDS,

yielding five microstates. For the

males, any of the four could have cast the first PDS vote, leaving only three

to cast the other PDS vote. This yields

12 possible combinations, but since order is not important, these are reduced

to six microstates for the males.

Assigning letters to each male voter – a, b, c, and

d – the PDS and non-PDS voters may be enumerated: (1) ab, cd

(2) ac, bd (3) ad, bc (4) bc, ad (5) bd,

ac and (6) cd, ab.

Combining the five female allocations with the six male allocations

produces a total of 30 microstates for the second mesostate. There are 40 microstates associated with the

third mesostate (ten ways to allocate the five females and four for the males)

and ten associated with the fourth (ten for the females and one for the

males). Since the third mesostate has

the most possible microstates, the EMax procedure chooses it is the maximum

likelihood solution. A more detailed

description of the EMax procedure is found in Chapter 5 and Appendix 3 of

Johnston (1985)

This example

above, however, only uses two constraints, the row and column sums as in King’s

EzI method. To increase the accuracy of

the results, EMax requires an additional sum over all districts in the study

area to obtain its estimates; it generates these numbers from the survey data,

in this case, the ratio of men (and women) who voted for the PDS. EMax applies the same maximum likelihood

procedure as in the example, but ensures that none of the mesostates violates the

added global constraints. Since we are

interested in who voted for the PDS not just in one district, but for each of

the 78 Wahlkreise of Berlin, the

above example can be extended by including row and column sums for each

district, and global sums from Berlin-wide survey data. The three sums required are thus (i) the

votes for the PDS and for all other parties within each of the 78 Wahlkreise, (ii) the voter turnout by

gender for each Wahlkreis, and (iii)

the Wahlkreis totals of PDS and

non-PDS votes by gender for all of Berlin.

Note again that items (ii) and (iii) require additional information not

used by King’s method. Item (iii) can be

derived directly from Berlin survey data but item (ii) must be estimated by

performing an additional EMax calculation since no such turnout data by gender

are available for each district. The

sums for this additional EMax procedure are (i) the voter turnout for each

district, (ii) the number of registered voters by gender, and (iii) the

citywide turnout by gender. Again, item

(iii) is available from the survey data.

The estimated results from this EMax calculation were then used as input

to the second estimation. The

implementation of the EMax procedure uses an iterative process to estimate the

results. It terminates after the maximum

number of iterations are complete or when the threshold parameters are

met.

The same double EMax technique

was also used to determine the spatial distribution of PDS support by age. Citywide polling data (Bömermann, 2001)

provided total turnout by age group (18-34, 35-59, 60+) for the first EMax

calculation, and Statistisches Landesamt Berlin (1999) provided total

PDS votes by age for all of Berlin.

Though this double EMax technique introduces additional error, the

aggregate results of the procedure are very similar to the survey results, with

EMax estimates within two percent of survey results (Table 3). In order to get the global input indexes for

the EMax, the values from the postal survey were recalculated by weighting the

disaggregated group values by the number of voters in each age group. This weighting produced estimates of turnout

for the 18-35 age group of 52.32%, for 35-60 years of 67.23%, and for over 60

of 75.10%. Similar weighting adjustments

were made for the PDS vote for the same age groups which yielded city-wide

estimates of 19.2% support for the party among 18-35 year olds, 19.9% for the

35-60 year olds, and 15.6% for those over 60 (Table 3).

Ecological Inferences of Turnout and PDS Vote in

Berlin, 1999

One of the major drawbacks to the

widespread use of the entropy maximizing methods is the limited availability of

the kinds of polling data that are needed to “drive” the method (Johnston and

Pattie, 2000). Berlin is a good test of

the respective values of the two ecological inference methods. We can compare the EzI estimates to the

survey estimates for the whole city (global estimates) and we can correlate and

compare the individual estimates of the two methods for the 78 Wahlkreise. We are thus making a double comparison - of

the similarity of the estimates of the two methods and of the methods to the

survey data. Of course, this latter

comparison is valid only if the survey data are accurate and this appears to be

the case as the close correspondence with the actual voting statistics

indicates (Bömermann, 2001).

The summary

ecological estimates are presented in Table 3, with the survey data also

presented for comparison. Since the

survey data are only available for 1999, the EMax estimates can only be

presented for that year and similarly, the EzI estimates for 2001 cannot be

verified by survey data. It is clear

that EMax provides a much better global estimate for the 1999 election than

EzI, as might be expected from the fact that the global survey results are used

to constrain the EMax values. The EzI

values are worrying, however, since the estimates are off by more than 10% for

the groups of interest. By contrast, the

EMax values are within 2-3% of the survey results. While no check can be made on the estimates

of the turnout of the PDS supporters from the survey data (it is impossible to

calculate a reliable value using the turnout estimate which are only available

for age groups, gender, and location in East or West Berlin), the PDS turnout

support is lower than the citywide average (65.6%). However, McKay (2000, 7) notes that there

tends to be a high correlation between strong support for the PDS and a higher

than average turnout.

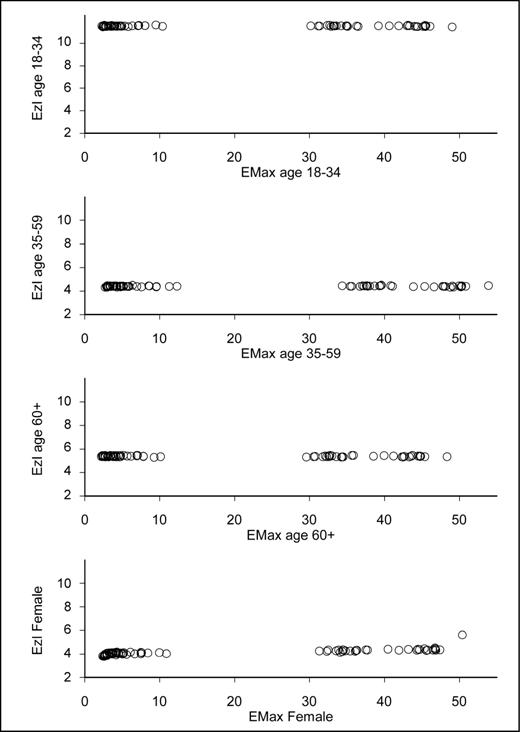

Figure 3 – Comparisons of the initial

ecological inferences of the PDS support (%) among different demographic groups

in the 78 Wahlkreise (election

districts) of Berlin, using entropy maximizing (EMax) and King’s ecological

inference method (EzI).

To

try to understand why the EzI estimates are so far off the EMax values and the

survey results, we probed their distributional properties. Simple plots of the two sets of ecological

estimates (Figure 3) indicates the nature of the problem. In all four of the plots, while the EMax

estimates show a dramatic range (from 2% to over 50%) reflecting the actual

performance of the PDS in the 78 Wahlkreise

of Berlin, the EzI estimates are essentially invariant across the city, showing

only a few percentage points difference between East and West Berlin. This result is clearly inaccurate since the

maps in Figure 2 show a huge geographic spread of values, with the former Wall

Clearly,

EzI does not provide reliable estimates for either the global values or the

values for the electoral sub-units in Berlin.

To try to understand why this is the case, we examined the graphical

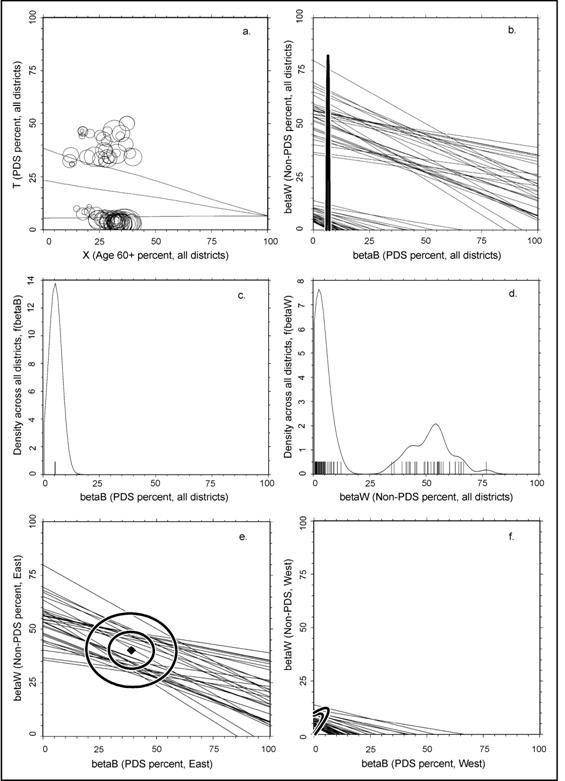

plots that are part of the optional output from the EzI program. Figure 4 displays the key indicators; a close

examination of the graphs shows both the inadequacies and benefits of King’s

ecological inference method. The basic

distribution of the data used to make the inferences is shown in Figure

4a. In this case, the aim is to estimate

the ratio of voters age 60 and over that supported the PDS. The size of the circle is proportional to the

number of voters in each Wahlkreis and

clearly, the difference between the districts in East and West Berlin is seen

in the two separate clusters of high and low PDS support. By contrast, the variation in the

distribution of the old population in the two parts of the city is not nearly

so great. The problem for the EzI

estimation can be seen in the lines on the graph, indicating the maximum likelihood

estimates (for the relationship of age over 60 and the PDS support). The middle line is the expected value of PDS

vote percentage given the ratio of the over 60 population and the other two

lines represent the 80% confidence intervals (King, 1997, 206). Only a small number of values fall within the

confidence bands as the maximum likelihood estimation procedure fails to pick

up the bi-modal (east and west Berlin) nature of the distribution.

Figure 4 – Distributional

Properties and Estimates of the Ecological Inferences of the PDS Vote in Berlin

1999. All the graphs are generated in

the EzI program (King, 1997).

In

Figure 4b, all possible combinations (tomography lines) of each pair of values

(for PDS and non-PDS support of the over 60 population) are plotted; the

posterior distribution of the quantity of interest is also shown. It is clear that aggregation bias is present

(the correlation between the district parameters and the independent variable, age

over 60). The bounds (where the tomography

lines cross the axes) are very wide, making accurate inferences difficult. Further evidence of the binary nature of the

Berlin data is provided in Figures 4c and 4d that show the density plots of the

estimated (inferred) district values for the PDS and the non-PDS votes. While the PDS distribution is peaked and

narrowly bounded around a mean of 5.4% (Figure 4c), the bi-modal nature of the

non-PDS vote shows that this distribution (Figure 4d) is not the antithesis of

the PDS vote, as it should be. The peaks

of this distribution at 5% and 55% show that this EzI modeling is flawed and

that alternative procedures are needed to generate reliable estimates for the

city as a whole and for its 78 constituent districts. King (1997, Chapters 9 and 16) offers

procedures to deal with such distributional issues, including non-parametric

estimation. In the case of Berlin,

however, it is obvious that the distributional problems are the result of the

bifurcated electorate in the city and it is evident that this key piece of

information should be used to derive the ecological inferences.

Figures

4e and 4f present the results of the EzI modeling using separate models for the

two parts of Berlin. Of course, the

division of the city for this modeling reduces significantly the number of

cases available – 32 for East Berlin and 46 for West Berlin. The tomography plots with the contour lines

contain the points with the highest probability of containing the true

estimates for each part of the city. The

black diamond shows the locations of the most likely values. The respective estimates of the support of

the over 60 population for the PDS are 38.2% for East Berlin and 2.8% in West

Berlin, which are a lot closer to the “true values” (from the survey data of

39% and 2.4% respectively) than the initial pooled citywide estimates. The Berlin example has clearly shown the

importance of careful consideration of the distributional qualities of the data

and the requirement that the researcher using EzI be familiar with the characteristics

of the data, as King repeatedly stresses in his book.

A

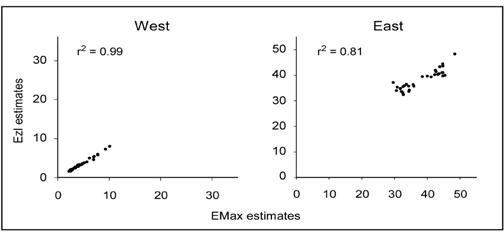

final check on the validity of the EzI estimates is a plot of the values for

the 78 Wahlkreise against the estimates generated by the Emax procedure; the plot is presented

for East and West Berlin separately in Figure 5. Johnston and Pattie (2001) have shown how a

comparison of the two sets of estimates, one derived from a statistical

simulation and the other from mathematical assignment, can offer creditability

to both methods if they correspond closely.

As can be seen in Figure 5, the correlation is very close for West

Berlin (all values very close to the diagonal) with a r2 value of

.99. In East Berlin, also, with a wider

spread of values, the correlation is high (r2 = .81) though there is

more scatter around the diagonal. We

conclude that the bifurcation of the Berlin data set, suggested by the

distribution plots of the initial EzI model and the evident indications of

aggregation bias, was the correct modeling option since the second set of

estimates match closely both the global city estimates (from the survey data)

and the local estimates (from the EMax proportions). Like any estimate, there is clear variation

around the EzI numbers and though these are maximum likelihood estimates, they

are not infallible. As King (1997)

notes, it is always valuable to check the EzI estimates to “true” values if

they are available. While absolute truth

is an elusive quality in survey data, the size and representativeness of the

October 2001 mail sample in Berlin suggests a close fit to the actual

numbers. The recalculated EzI values

match the survey data very well.

Unfortunately, such survey results are not available for the smaller

geographic unit of the Wahlkreis and so, the only check available at

this scale is against the EMax values.

Figure 5 - The Relationship between the EzI and EMax

Estimates of the PDS Vote among Voters aged 60 and Over, Berlin 1999.

The

Geographic Distribution of the PDS Support in Berlin

Having demonstrated the reliability of

the EzI and the EMax estimates for Berlin in 1999, we turn now to the

distribution of these values across Berlin’s districts, paying close attention

to the effects of the division of the city along the Wall and to the clustering

of values in certain parts of the city.

While both sets of ecological estimates could be used in this exercise,

we used the EMax values, except in the case of the turnout estimates which

could only be derived using EzI.

In

examining the political geography of the PDS vote, we turn to three standard

tools of spatial analysis – cartographic displays, Morans I index and the ![]() statistic. Recourse to these tools is growing quickly

and with the integration of statistical models with computer mapping packages,

it is expected to grow even faster (O’Loughlin, 2002). The global clustering of the estimates are summarized by the

Morans I values and the associated Z-values in Table 4.[1] It is evident that

the PDS vote is strongly clustered in Berlin in both 1999 and 2001 and that

there is very little difference in the levels of concentration of the first and

second vote. The distributions of the

votes in Figure 2 anticipated this result, especially since the former Berlin

Wall still acts as a major dividing line in the political culture of the city.

statistic. Recourse to these tools is growing quickly

and with the integration of statistical models with computer mapping packages,

it is expected to grow even faster (O’Loughlin, 2002). The global clustering of the estimates are summarized by the

Morans I values and the associated Z-values in Table 4.[1] It is evident that

the PDS vote is strongly clustered in Berlin in both 1999 and 2001 and that

there is very little difference in the levels of concentration of the first and

second vote. The distributions of the

votes in Figure 2 anticipated this result, especially since the former Berlin

Wall still acts as a major dividing line in the political culture of the city.

Table 4. Row Standardized Moran's I for PDS Vote and Turnout

The

ancillary question to the clustering of the PDS vote is whether there is a

similar trend in the estimates of the ratios of the various age groups that

supported for the PDS. Based on the EMax

estimates, it is clear from the Morans I values in Table 4 that the level of

clustering is very similar or stated another way, the geographic clustering of

the age components of the PDS vote are consistent. It appears to make little difference which

socio-demographic component of the PDS support is examined. All show a strong concentration of high values

in the same region of East Berlin and low values in the west of the city. In this Berlin example, geography clearly

outshines any socio-demographic explanation for the variation in the support of

the PDS.

While Morans I provides an effective

summary of the overall level of clustering, it is not capable of distinguishing

the nature of clustering. Is the high

value of the index the result of one large concentration or multiple smaller

ones? In order to distinguish between

these possibilities, we use an index of local association, the![]() statistic.[2] Mapping these

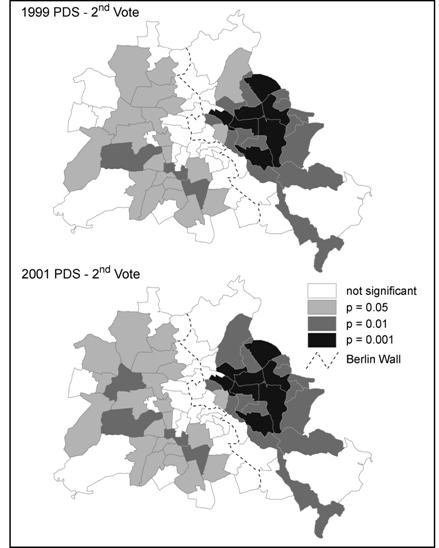

statistic.[2] Mapping these ![]() values for each of the 78 geographic units in Berlin clearly

shows the core of the PDS support and the changes that occurred between 1999

and 2001 (Figure 6). The most

significant positive values (associated with similar values in contiguous Wahlkreise)

are found in the same districts in 1999 and 2001, predominantly in the Bezirke

of Marzahn, Lichtenberg and

Hohenschönhausen. These districts were

predominantly working-class districts in the Communist years and have not yet seen

the kind of improvements that have characterized the central parts of the

former East German capital (Cochrane and Jonas, 1996; Cochrane and Passmore,

2001). Around this core of highest

support, most of the other voting districts in East Berlin also show highly

significant values. Only in the extreme

northern district of Pankow and in the neighborhoods along the former Wall are

there zones of non-significant

values for each of the 78 geographic units in Berlin clearly

shows the core of the PDS support and the changes that occurred between 1999

and 2001 (Figure 6). The most

significant positive values (associated with similar values in contiguous Wahlkreise)

are found in the same districts in 1999 and 2001, predominantly in the Bezirke

of Marzahn, Lichtenberg and

Hohenschönhausen. These districts were

predominantly working-class districts in the Communist years and have not yet seen

the kind of improvements that have characterized the central parts of the

former East German capital (Cochrane and Jonas, 1996; Cochrane and Passmore,

2001). Around this core of highest

support, most of the other voting districts in East Berlin also show highly

significant values. Only in the extreme

northern district of Pankow and in the neighborhoods along the former Wall are

there zones of non-significant ![]() values. It is in these

regions that gentrification and re-development is proceeding fast, transforming

not only the streetscape but also, changing the population composition of the

increasingly-richer zones (Krätke, 2001; MacDonagh, 1998; White and Gutting,

1998). In West Berlin, the

values. It is in these

regions that gentrification and re-development is proceeding fast, transforming

not only the streetscape but also, changing the population composition of the

increasingly-richer zones (Krätke, 2001; MacDonagh, 1998; White and Gutting,

1998). In West Berlin, the ![]() significance values are defined by the similarity of low PDS

percentages to similar values in the surrounding districts. Between the two zones of significance is

central Berlin, the districts along the former Wall and the historic center of

the city that was built-up by the mid nineteenth-century. These are among the

most dynamic in terms of population change and mixed in demographic composition

(Cochrane and Passmore, 2001). If the

PDS is going to expand and grow beyond its East Berlin core, it is these

neighborhoods that offer the best possibilities where the PDS will be competing

for voters with the SPD and the Green party in future elections.

significance values are defined by the similarity of low PDS

percentages to similar values in the surrounding districts. Between the two zones of significance is

central Berlin, the districts along the former Wall and the historic center of

the city that was built-up by the mid nineteenth-century. These are among the

most dynamic in terms of population change and mixed in demographic composition

(Cochrane and Passmore, 2001). If the

PDS is going to expand and grow beyond its East Berlin core, it is these

neighborhoods that offer the best possibilities where the PDS will be competing

for voters with the SPD and the Green party in future elections.

Figure 6 - Distribution of the ![]() Indexes of the PDS

Vote Percentages by Wahlkreis in Berlin, 1999 and 2001.

Indexes of the PDS

Vote Percentages by Wahlkreis in Berlin, 1999 and 2001.

The composition of the PDS vote

can be examined using the EMax estimates of the level of support by age

group. The survey results in Berlin

showed that the PDS gained more support from older voters in East Berlin (31.6%

of those aged 25 to 34 compared to 39% for those age 60 and more) and from

younger voters in West Berlin (6.0% for 25 to 34 year olds and 2.4% for those

60 and older) (Bömermann, 2001). Gender

differences were tiny (they are not examined further) and were dwarfed by the

geographic difference across the former Wall.

In the East, younger women were more supportive of the PDS but after age

45, men gave slightly more support to the party. As in most democracies, turnout increased

with age for both genders in both parts of the divided Berlin.

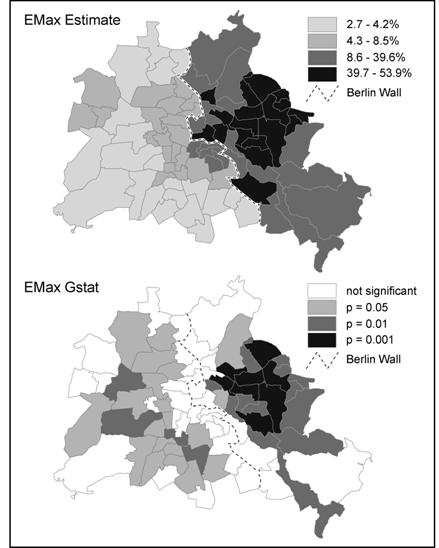

Mapping both the estimates and the ![]() statistics for the estimates allows a consideration of the

differential character of the PDS appeal across the city. While Figure 7 shows the estimates for the

35-59 age group (the largest age-defined voting block in the city), the maps

for the other age groups are very similar and are not shown here. In approximately half of the Wahlkreise

in East Berlin in the 1999 election, the PDS received more than 39.7% of the

vote of the middle-aged population, significantly higher than their overall

ratio in the city (17.7%). It is clear

from the maps in Figure 7 that the more economically-deprived regions of the

East are where the party does best. Not

only is the PDS a regional-protest party, claiming to represent all Easterners,

but it also gains added support from the poorer segments of the East German

population, attracted by its leftist ideology and its historical claim to voice

the interests of the working-class (McKay, 2000; Segert, 1998). In contrast to the core support in the East

is the very weak support in the richest parts of West Berlin where the party

received less than 5% of the vote in many voting districts. The

statistics for the estimates allows a consideration of the

differential character of the PDS appeal across the city. While Figure 7 shows the estimates for the

35-59 age group (the largest age-defined voting block in the city), the maps

for the other age groups are very similar and are not shown here. In approximately half of the Wahlkreise

in East Berlin in the 1999 election, the PDS received more than 39.7% of the

vote of the middle-aged population, significantly higher than their overall

ratio in the city (17.7%). It is clear

from the maps in Figure 7 that the more economically-deprived regions of the

East are where the party does best. Not

only is the PDS a regional-protest party, claiming to represent all Easterners,

but it also gains added support from the poorer segments of the East German

population, attracted by its leftist ideology and its historical claim to voice

the interests of the working-class (McKay, 2000; Segert, 1998). In contrast to the core support in the East

is the very weak support in the richest parts of West Berlin where the party

received less than 5% of the vote in many voting districts. The ![]() map in Figure 7 is very similar to those of Figure 2 and

indicates again that the PDS vote does not vary as much within the

socio-demographic categories (by age group, by gender, by education, by income)

as it does across the former Berlin Wall.

map in Figure 7 is very similar to those of Figure 2 and

indicates again that the PDS vote does not vary as much within the

socio-demographic categories (by age group, by gender, by education, by income)

as it does across the former Berlin Wall.

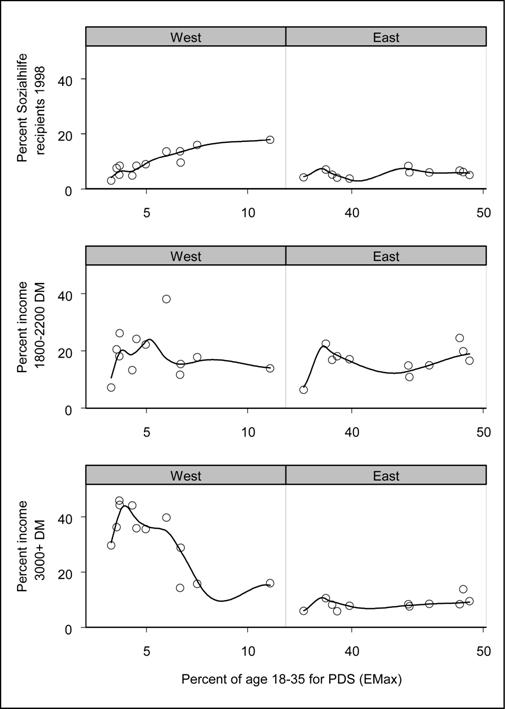

The dramatic importance of

the geographic divide in Berlin compared to the small differences between the

usual socio-economic categories is further illustrated in Figure 8. Unfortunately, socio-economic data are not

available for the 78 Wahlkreise and we had to turn to the income data

from the micro-census that was conducted in Berlin in 1995 (Statistisches Landesamt Berlin, 1996)

and social welfare data collected yearly by

Figure 7 - Distribution of the EMax Estimates of PDS

Support among 35-59 Year Old Voters and ![]() Indexes by Wahlkreis in Berlin, 1999.

Indexes by Wahlkreis in Berlin, 1999.

the Statistisches

Landesamt. These data were

reported for the 23 Bezirke of the city (before the municipal reform)

and by matching the Wahlkreise EMax estimates of the young voters (18-34

years old) to the Bezirke , e were able to develop the trellis plots of

Figure 8. (Trellis graphs are

conditioning plots with one or both axes further divided to illustrate key data

relationships; see Chambers et al.,

1983). On these graphs, the small

circles indicate the respective values for the 23 Bezirke (see Figure 1 for

their locations and boundaries) and the line indicates the loess curve. (Loess is a technique that uses

non-parametric regression procedures and is widely used in graphics

visualizations. It fits a function of the predictor variables in a moving

fashion that is analogous to a moving average in a time series. We used the S-Plus statistical package for

the modeling; see Cleveland, 1993 and Venables and Ripley, 1997). Loess modeling has the advantage of

summarizing non-linear relationships to highlight general trends. The income and welfare categories chosen here

are for illustration and do not cover all possibilities but their display

clarifies the divisions of the city.

In the highest

income category (monthly household net income of more than 3000

Figure 8 – Trellis Plots of the EMax Estimates of PDS Support among 18-35

Year Olds by Bezirk in Berlin, 1999.

These trellis

plots for Berlin are highly unusual for a Western democratic election. They demonstrate clearly that party support

is not related to neighborhood income levels but, instead, is determined by the

location of the household, either west or east of the former Wall. Though geographers have claimed for decades

that a voter’s location in the urban fabric is a small but important part of

the explanation of the electoral choice, the example of contemporary Berlin

clearly shows that it can be the most significant factor - far exceeding any of

the usual socio-demographic explanations.

While we are not arguing that Berlin represents any kind of typical

scenario for the future, it is perfectly clear that the legacy in the city

emanating from the Cold War division is still dominant in the electoral

landscape of the PDS, and by extension, to the other parties. As German electoral politics adapts to the

conditions of the post-Wall world, the speed with which this electoral canyon

is filled will be a good indicator of the resumption of normal Western-style

electoral politics.

The final

analysis reports the result of the EzI estimation of the turnout of the PDS

voters. In this modeling, the T variable

(the ratio we wish to calculate) is turnout while the X variable (used to make

the calculation) is the PDS 1999 and 2001 second vote. We had to resort to EzI because no citywide

estimates are available from census data for the relative turnout of PDS

supporters and non-PDS voters. For the

city as a whole, we estimated that the turnout of PDS supporters was 54.1% in

1999 and 55.5% in 2001, compared to citywide averages of 65.6% and 68.2% respectively. Turnout since the unification of Berlin has

been consistently lower in the eastern half of the city, the location of the

PDS core supporters. The lower turnout

partly reflects a disillusionment in the former GDR with the nature of the

German political system (Segert, 19989).

It has the effect of reducing the potential PDS membership of the state

parliaments and the Bundestag and suggests that a larger pool of PDS voters

might be mobilized to go to the polls.

The geographic

distribution of the turnout of PDS voters in Berlin is shown for 1999 and 2001

in Figure 9. Some voters in core PDS

areas will not vote because they think that the party is mobilizing its voters;

in areas with few PDS voters, their supporters might be more mobilized to vote

than the average voter in these neighborhoods.

In Figure 9, parts of East Berlin showed more than 60% turnout in 1999

but other Wahlbezirke had PDS voter

turnout as low as 50%. By 2001, the

turnout of PDS supporters increased in most districts and nine Wahlkreise in West Berlin showed significantly

more than average PDS turnout. It is in

the older and poorer parts of East Berlin and the richest parts of West Berlin

that the PDS voter turnout remains lowest.

Like most turnout displays, the maps in Figure 9 correspond to income

for East Berlin (lower income neighborhoods have lower turnout) but the

relationship becomes more complex for West Berlin where the special character

of the PDS party supporter defies the usual expectations.

Figure 9 - Distribution

of EzI Estimates of the Turnout of the PDS Supporters by Wahlkreis in

Berlin, 1999 and 2001.

Data limitations

prevent a more complete analysis of the socio-demographic components of the PDS

vote in Berlin. The lack of adequate

census data for the small areal units is especially discouraging since it

precludes the fitting of ecological inferential models for groups defined by

educational attainment, housing status, and occupation. Nevertheless, within the limitations of

existing data, we have shown clearly that the division of the city into its

eastern and western sectors along the line of the former Berlin Wall far

surpasses any compositional explanation of the vote for the PDS. Depending on which side of the geographic

divide they sit, different groups come together to vote in approximately the

same proportion for the party. Old and

young voters in West Berlin are much more alike than their age counterparts on

the other side of the former Wall. After

a decade of elections to state and federal parliaments, this divide is not

easing and is strengthening in some ways as the dominance of the PDS in the

eastern half of the city grows.

Conclusions

This geography of the PDS vote in Berlin

shows that “die Mauer in den Köpfen” is still a reality in German

elections. In his 1991 poem, “Die Mauer”

(The Wall), Reiner Kunze (1998) anticipated this development - “Als wir sie

schleiften, ahnten wir nicht, wie hoch

sie ist in uns” (“When we tore it down, we did not guess, how high it is in

us”). At the national level, the growing

support of the PDS is challenging the two main parties, the Christian Democrats

and the Social Democrats, to try to hold onto the eastern support that they

worked assiduously to cultivate in the aftermath of the unification in

1990. If either party loses its relative

standing in the east to the PDS, its claim to be a national party will be

hollow. After a decade of unification,

there is little sign that the large electoral and ideological differences

between East and West are ebbing. In

fact, one could argue that they are magnifying as the PDS goes from strength to

strength on the basis of an appeal that remains partly ideological (left-wing)

and partly regional identification. In

its September 2002 electoral campaign, the party is using slogans such as “That

no one loses is the aim”, “New jobs – the basis for social equality and

readiness for the future”, and “ From Germany’s edge to Europe’s middle – East

Germany needs a new beginning”, mixing a left-wing appeal with a regional

advocacy. It is running candidates in 13

single-member constituencies in the former West Germany, as well as 38 in the

former GDR; the party is expected to get party-list seats by exceeding the 5%

national hurdle and will almost certainly increase its current representation

of 37 in the Bundestag. On the basis of

public opinion polls, the PDS is predicted to gain about 6% of the German-wide

vote in the September 2002 federal elections (Die Welt, 26 June, 2002).

Berlin

is a city undergoing dramatic change, in its economic profile, in its streetscapes,

in its international linkages, and as a new national center of globalization in

Germany. Unlike other east European

countries, where former Communist parties were devastatingly tainted by their

behavior during the Cold War division of the continent, the PDS has managed to

re-create itself as a protector of regional interests and as the voice of those

who have been negatively affected by the incorporation of the socialist East

into the capitalist West. No other

former Communist country disappeared like the GDR so there cannot be any

certainty that a similar party could not have arisen elsewhere. Perhaps the closest parallel to the PDS is

the Lega Nord in Italy which has advocated the economic interests of the North

of the country in the aftermath of the shake-up of Italian politics in

1992. But Italy has not undergone the

massive economic and political shifts that have characterized the former

GDR. In Berlin, the post-Communist

changes have been dramatic and the contrasts greater than elsewhere because of

the proximity of the Western part of the city and the huge redevelopment

projects in the center.

Using

new methodologies of inferring individual behavior from aggregate data, we have

shown in this paper that the usual compositional factors that political

scientists rely on to understand electoral behavior are severely limited for

the PDS experience in contemporary Berlin.

The party’s appeal is highly focused on one part of the city and cuts

across all demographic groups in that region.

By contrast, its appeal in the West is tiny, though it is showing signs

of penetrating previously-strong areas of support for the Greens and for the

Social Democrats in the older and poorer parts of the West. To break out of its eastern bailiwicks, the

PDS will have to make further inroads into the poorer Western neighborhoods

where unemployment remains high. To accomplish this, it will have to take votes

away from its partner in the Berlin coalition government, the SPD. Much depends on the perception of the PDS’

performance while in power in the city.

Berlin is thus a test case of the future profile of the German electoral

scene and an intriguing example of the ability of a party to move from a

regional to the national stage.

__________________________________________________________________________________

Bibliography

Barker, Peter, ed. The

Party of Democratic Socialism in Germany. Atlanta, GA: Rodopi, 1998.

Bauer-Kaase,

Petra, “German

Unification: The Challenge of Coping With Unification,” in W. Donald Hancock

and Helga Walsh, eds., German

Unification: Processes and Outcomes. Boulder:

Westview Press, 1994, 285-313.

Bauer-Kaase,

Petra and Max Kaase,

“Five Years of Unification: The Germans on the Path to Inner Unity?” German Politics 5, 1: 1-25, April 1996.

Baylis,

Thomas A.,

“Institutional Destruction and Reconstruction in Eastern Germany,” in Patricia

Jo Smith, ed., After the Wall: Eastern

Germany Since 1989. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1998, 15-33.

Becker-Cantarino, Barbara, “Reflections on a Changing Berlin,” in Barbara

Becker- Cantarino, ed., Berlin in Focus: Cultural Transformations in

Germany. Westport, Connecticut; Praeger, 1996, 1-35.

Bolzen,

Stefanie, “Der

Antikriegkurs brachte der PDS die meisten Stimmen (The Anti-War Course Brought

Most Votes to the PDS).” Die Welt 2, 23

October 2001.

Bömermann, Hartmut, “Die Wahl zum Abgeordnetenhaus

von Berlin am 10. Oktober 1999: Ergebnisse der repräsentativen Wahlstatistik

(The Election of the Berlin House of Parliament on 10 October 1999: Results of

Representative Election Statistics)” Berliner

Statistik Monatschrift 1/01, 14-23, 2001.

Borneman,

John, Belonging

in the Two Berlins. Kin, State, Nation. New York: Cambridge University

Press, 1992.

Brie,

Michael, “Das

Politische Projekt PDS – eine unmögliche Möglichkeit (The PDS Political Project

– An Impossible Possibility),” in Michael Brie, Martin Herzig and Thomas Koch,

eds., Die PDS: Empirische Befunde und

kontroverse Analysen (The PDS:

Empirical Results and Controversial Analyses). Cologne: PapyRossa Verlag, 1995, 9-38.

Chambers, John M., William S. Cleveland, Beat Kleiner, and Paul

A. Tukey, Graphical Methods for Data Analysis. Belmont, CA: Duxbury Press, 1983.

Cleveland

William S., Visualizing Data. Summit, NJ: Hobart

Press, 1993.

Cochrane,

Allan and Andrew Jonas, “Re-imagining Berlin: World City, National Capital or Ordinary

Place?” European Urban and Regional

Studies 6, 2:145-164, April

1999.

Cochrane,

Allan and Adrian Passmore, “Building a National Capital in an Age of Globalization: The Case of

Berlin,” Area 33, 4: 341-352, October 2001.

Conradt,

Cooper,

Belinda, “The

Changing Face of Berlin,” World Policy

Journal 15, 3: 57-68, Fall 1998.

Dalton,

Russell J. and W. Bürklin, “The Two German Electorates,” in Russell J Dalton, ed., Germans Divided: The 1994 Bundestag

Election. Washington D.C.: Berg,

1996, 183-209.

Davies-Withers,

Suzanne, “Quantitative Methods: Advancement in Ecological

Inference,” Progress in Human Geography 25,

1:87-96, January 2001.

Deggerich, Markus, “Das PDS

–Problem der SPD (The PDS – Problem for the SPD),” Der Spiegel 21

October, 2001,

Doud,

Duke

Vic and Keith Grime,

“Inequality in Post-Communism,” Regional

Studies 31, 9: 883-890, December

1997.

Eith,

Ulrich, “New

Patterns in the East? Differences in

Voting Behavior and Consequences for Party Politics in Germany,” German

Politics and Society 18,

3:119-136, Fall 2000.

Elkins,

Thomas H. and Burkhard Hofmeister, Berlin: The Spatial Structure of a Divided

City.

London:

Methuen, 1988.

Ertman,

Thomas, “Eastern

Germany: Ten Years after Unification,” German Politics and Society 18, 3: 1-12, Fall 2000.

Evans,

Geoffrey and Stephen Whitefield, “Economic Ideology and Political Success:

Communist-Successor Parties in the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Hungary

Compared,” Party Politics 1, 4:565-578, October 1995.

Fotheringham,

A. Stewart, “A Bluffer’s Guide to ‘A Solution to the Ecological

Inference Problem’,” Annals, Association

of American Geographers 90,

3:582-586, September 2000.

Gibowski,

Wolfgang G.,

“Germany’s General Election in 1994: Who Voted for Whom,” in

Higley,

John, Judith Kullberg, and Jan Pakulski, “The Persistence of Post-Communist Elites,” Journal of Democracy 7,

2:133-147, April 1996.

Hough,

Daniel, “’Made

in Eastern Germany’: The PDS and the Articulation of Eastern German Interests,”

German Politics 9, 2: 125-148,

August 2000a.

Hough,

Daniel,

“Societal Transformation and the Creation of a Regional Party: The PDS as a

Regional Actor in Eastern Germany,” Space and Polity 4, 1: 57-75, May 2000b.

Howard,

Marc M., “An

East German Ethnicity? Understanding the New Division of Unified Germany,” German Politics and Society 13, 4: 49-70, Winter 1995.

Ishiyama,

John T.,

“Discussion and Conclusions,” in John T. Ishiyama, ed., Communist Successor Parties in Post-Communist Politics. New York:

Nova Scotia Publisher Inc, 1999a, 299-334.

Ishiyama,

John T.,

“Introduction and Theoretical Framework,” in John T. Ishiyama, ed., Communist Successor Parties in

Post-Communist Politics. New York: Nova Scotia Publisher Inc, 1999b, 1-12.

Ishiyama,

John T., “What

Kinds of Parties are Emerging? Patterns of Successor Parties Organizational

Development,” in John T. Ishiyama, ed., Communist

Successor Parties in Post-Communist Politics. New York: Nova Scotia

Publisher Inc, 1999c, 131-151.

Johnston,

Ron, The Geography of English

Politics- The 1983 General Election. London: Croom Helm, 1985.

Johnston, Ron, Review of Gary King, A Solution to the Ecological

Inference Problem: Reconstructing Individual Behavior from Aggregate Data. Environment

and Planning A 30, 7: 1323-24, July 1998.

Johnston, Ron and Charles J. Pattie, “Ecological Inference and

Entropy-Maximizing: An Alternative Estimation Procedure for Split-Ticket

Voting,” Political Analysis 8, 4:333-45, Fall 2000.

Johnston, Ron and Charles J.

Pattie, “On

Estimates of Split-Ticket Voting” (Available from http://www.people.fas.harvard.edu/~burden/papers.html),

2001.

King, Gary, A Solution to the

Ecological Inference Problem: Reconstructing Individual Behavior from Aggregate

Data. Princeton, NJ: Princeton