Moscow as an Emergent World City: International Links, Business

Developments and the Entrepreneurial City**

Vladimir Kolossov*, Olga Vendina*, and

John O�Loughlin**

*Institute of Geography

�Russian Academy of Sciences

Staromonetny per.� 29

109017 Moscow,

Russia

Email:� polgeogr@igras.geonet.ru

** Institute of Behavioral Science

University of Colorado at Boulder

Campus Box 487

Boulder, CO.�

80309-0487, USA

Email: johno@colorado.edu

**Professor

Kolossov is Head of the Center of Geopolitical

Studies, Institute

of Geography, Russian

Academy of Sciences and Dr. Vendina

is a researcher in the Institute of Geography,

Russian Academy

of Sciences; Professor O�Loughlin is a Professor of Geography in the Institute

of Behavioral Science at the University

of Colorado, Boulder.� This research was supported by a research

grant from the Russian Foundation for Fundamental Studies N 01-06-80157 to Vladimir

Kolossov and by a National Science Foundation (United

States) research grant to John

O�Loughlin.�� Comments on an earlier

version of the paper by Professor Beth Mitchneck, University

of Arizona at the Annual Meeting of

the Association of American Geographers in New York

and the research assistance at the University

of Colorado of Altinay

Kuchukeeva, Clionadh Raleigh and Tom Dickinson are gratefully

acknowledged.

Abstract

Using the �Informational City� concept of Manuel Castells and its

extension into the world-city literature, this paper examines contemporary

strategies of urban management in Moscow.� The focus is on the international

communication trends that are transforming Moscow into an Informational City, manifested locally in the establishment of various types of

business districts.� On the basis of

detailed data (local post offices zones) in Moscow, the location of diverse

business facilities, their restriction to particular types of urban

environments, their relation to the geography of government organization, and

the location of the financial sphere and trade (especially in luxury items) are

analyzed.� Like other world cities, the

transformation of Moscow from a Soviet to an Informational City has produced a polarized city, one that increasingly that fits the �citadel-ghetto�

model.� While a concerted effort of the

state, municipal authorities and private capital encourages the growth of

business districts, the interests of the majority of Moscovites

are ill served by the contemporary political structures and processes.

Russia's recent integration into the world economy

after 1991 in a time of market reforms and the dominance of Moscow in Russian

economic and political life have raised questions about the nature, causes and

rate of restructuring of the functions of the capital city.� Central to these concerns are the trends and

prospects of Moscow's conversion into a world city that will maintain

the political and social stability required for continued Western

investment.�� While the economic crisis

of August 1998 set back the rapid integration of Moscow into the European and world systems of city

networks, the past few years have seen a rebound of the global external

linkages established in the increasingly-market economy of Russia.� The

purpose of this paper is to examine the changes, both external and internal, in

the Moscow city economy and determine if the city is on a

sustainable path to status as a world city or whether Moscow remains the center of a network of cities that

are partially isolated from the rest of the world system.� Evidence for both points of view can be

gleaned from the recent work of Peter Taylor and his Loughborough University colleagues on world city formation (Beaverstock et al., 2000; Fossaert,

2001; Taylor, 2000; Taylor and Hoyler, 2000).� By gathering and analyzing recent data from

Russian sources, we can help to separate fact from fiction regarding economic

life in contemporary Moscow.� Though Moscow is not a typical Russian city,

its trajectory points to the future for other large post-Soviet cities.

Since the move of the capital from St. Petersburg

to Moscow in 1918, the Russian capital has been both an industrial and

governmental center, first for the Soviet Union and from 1945-1991, for the

broader Communist bloc.� During the Cold

War, Moscow�s links with the rest

of the world were spatially limited and highly constrained by political and

ideological considerations, a stark contrast to Western European cities.� Since 1991, Moscow has re-entered the world

system as a linchpin of Western investment and economic activity in the former

Soviet Union and the economic profile of the city, as well as its streetscape,

has changed profoundly as a result.�

Market reforms in Moscow,

embarked on the path of post-industrial development (Treivish,

Pandit and Bond, 1993) without a clear roadmap, have

revealed distinct characteristics of an �informational� city (Castells, 1989) as a stage on the way to "world city�

status.� Signs of such an evolution have

included an office boom, visible in the rental prices and evident to all

residents and visitors by the proliferation of cranes and construction sites in

central Moscow (Vendina, 1997); the creation of an infrastructure of� telecommunications, communications and urban

services, based� upon technology; the

establishment of national-international�

business centers; and a booming high-end retail sector in central Moscow

categorized by exclusive shopping centers and gallerias.� A proliferation of joint ventures between

local and Western capitalists and the upgrading of the �kiosk� economy to a

more formal retail environment mark Moscow

as the urban leader of the post-communist economic transition in the former Soviet

Union.� Compared to central

European cities like Prague, Warsaw and Budapest, Moscow still retains more vestiges

of the Communist era legacy and the dual-economic (Soviet and post-Soviet)

models coexist, sometimes uneasily, in a city undergoing dramatic changes.

(Between 1992 and 1996, the ratio of Moscovites in

federal and city government jobs dropped from 73% to 42% and stabilized

thereafter. (www.mos.ru/eko/eko-book-6.html).� We analyze this transition process and the

strategies of Russian federal and Moscow

city authorities in managing and promoting it.�

New international economic functions, as well as

the specific locational requirements of new

businesses for prominent office sites, coupled with a relatively tight supply

dating from before 1991, have made Moscow one of the most expensive cities for office rents.� At $700 per square meter per year, Moscow

ranks just behind Paris but is more expensive than Chicago, Stockholm, Berlin,

Madrid, Sydney and Brussels� (�Office

rents� Economist, January 20, 2001, 106). Yet, an international ranking

by an international consulting firm, William M. Mercer, of �quality of life�

(using 39 criteria ranging from recreational and transport facilities to crime

and education) ranks Moscow second-lowest of all big cities, just ahead of

Mumbai.� Moscow ranks well-behind Cairo,

Bangkok, Rio de Janeiro, Istanbul, and Buenos Aires, and, of course, European

and North American cities (�Quality of life� Economist, March 3, 2001,

98).� A profile of high prices for

international businesses and low quality of life for citizens and expatriates

is not untypical of Third

World business

metropolises; cities such as Sao Paolo and Mumbai have experienced it for

decades.� Whether Moscow will retain this dual city profile or whether the

new international linkages will result in trickle-down economic benefits to the

great majority of Moscovites is still in

question.� In this article, we also

examine the relationship between the new economic functions and the attractions

of the local urban environments since it is increasingly clear that certain

sites in the city are highly-prized while most of the city remains excluded

from the new business developments.

The Informational and World City Concepts

About

the same time as the end of the Cold War and Moscow�s re-integration into the globalizing world

economy, significant debate and research began among Western academics about

world-cities � their conformation, extent, structures, linkages, and global

distribution (Friedmann, 1986; Sassen,

1991).� Linked closely with the contemporaneous

proposal of Manuel Castells (1989) on the rise of the

�network society�, the world city literature is characterized by a strong

emphasis on Western, south-east and east Asian

metropolises, the �command and control centers� of the globalizing world economy

(Knox and Taylor, 1995).� In order to

examine Moscow�s characterization as a world city by the GaWc

(Globalization and World Cities) group at Loughborough

University� (Taylor, 2000), we need to

consider the key elements of the Informational City and world city literatures

to see if these concepts are accurately applied to Moscow a decade after the

end of the Soviet Union.

����������� Castells� (1989) central argument is that the technology of

the microchip produced advanced, information-based societies, first in key

Western locations and later, through rapid diffusion, in all parts of the

world.� By allowing instantaneous

communication between nodes on networks, the �deterritorialized

space of flows� has undermined the space of states (governmental control) and

instituted new realms of capital markets

and financial centers.� Control of these new spaces are critical for economic

prosperity in the new information age and conversely, exclusion from the spaces

of flows condemns regions and societies to economic marginalization and

dependency in the globalized world economy.�� The burgeoning development of tertiary

(service) and quaternary (research and development) spheres of activity in the

leading major world cities has produced restructuring urban functions and serves

as the basis for a growth strategy of municipal and national authorities.� In an Informational City, priority is

assigned to the tertiary and quaternary sectors of the economy as the

higher-order functions develop in a dynamic fashion; the city becomes not so

much a place of residence, production and consumption, but� one for decision-making, financial

activity, research, and higher education (Castells,

1989, 1996; Claval, 1994; Gottmann

and� Harper, 1990; Graham and Domini, 1991; Graham, 1994).� In other words, an Informational City becomes a place brimming with information and intense personal

business contacts, and a control center of the management of new information in

a globalized society and economy.� Therefore, crucial changes in the cities aspiring

to attain such status and get integrated into the world-wide network of

megalopolises are associated with the rapid development of the financial credit

sphere and management, representation activity, business services and

information technologies (O�Loughlin, 1992).

Four key features of an Informational City have been identified.� It is a

place that a) accommodates international, national, regional government, and

non-government organizations, authorized to make far-reaching political,

diplomatic, legal, economic, military and other decisions; b) that contains a

broad range of potential direct contacts among highly-differentiated

organizations, including adequate infrastructure and transport for such

contacts; c) that provides a high level of communication (accessibility), both

transport and informational, with other decision-making or global cities; and

d) that has organizational structures and institutes to amass and process

information essential for business development, political activity, etc., as well

as making available an appropriate choice of business facilities and a

producer-service sector (financial, consulting, banking, real estate,

accounting, advertising services).� The Informational City concept emerged at the junction of views on world cities and the new

informational society.� Castells (1993) noted that the Informational City is the urban expression of the whole matrix of determinations of the

informational society, just as the industrial city was the spatial expression

of the nineteenth-century industrial society.��

The processes constituting this new urban phenomenon are understood by

referring to contemporary social and economic trends that are restructuring

national territories.

����������� The

coming of the Informational City and the discussion of a post-modern stage of

societal development have revealed two approaches that serve as the basis for

the urban planning and management strategy.�

Logan and Molotch (1987) developed the concept

of the �city as a growth machine": the territory� of a city is used by political forces that

control it to increase combined rent permanently, turning a place or territory

into a commodity that is then �sold� on the real estate market.� This

approach is backed by state support of private investments but the adverse

social effects of the resulting growth are rarely compensated by state and city

governments.� The typical outcomes of

these processes are social polarization of the population, residential

functions forced out of the center of the city, and a break-up of the city

space into isolated, well-protected expanses owned by individuals or companies.

Harvey�s (1989a, 1989b) "entrepreneurial city"

concept offers a complimentary model of the post-modernist development of

megalopolises.� Harvey regarded the historical destinies of major cities

in a broader, global context in which there is stiff competition among the

cities as they vie for new investors.� To

withstand such challenges and keep the status acquired earlier, cities launch

ambitious and expensive programs of remodeling city centers in order to

re-create their favorable image.� At the

same time, states and municipalities are increasingly unable and reluctant to

cover social expenses involved in improving city centers.� To facilitate these changes, the paradigm of

the city management system is altered and transits from �traditional� to a so-called� �entrepreneurial�

management.� The new entrepreneurial

strategy of city management usually involves 1) public-private partnerships; 2)

a market-oriented nature for the entire activity; 3)

assumption by the municipalities of part of the risk associated with private

investments; and 4) participation of the local state in partnership with real

estate interests.

����������� In a bid to enhance their

competitiveness, including the rivalry with nearby and distant suburbs,

administrations of central cities set up business improvement districts, of

which there were over 1000 in the USA by the early 1990s (Mallett,

1994).� These districts are special

property tax zones that have been legally implemented for use in promoting

special services not available to other districts of the city.� These services include improvements in

transportation access, creation of an attractive urban environment, and ensuring

tidiness and security.� A private

non-commercial company, headed by managers elected from among the real estate

owners, usually runs a business improvement district.� For countries such as Russia or the new industrializing economies of South-East Asia, North American and European experience is

crucial when choosing rational, up-to-date city management strategies that, at

the same time, take account of context- specific international economic

features.�

World-cities were first described by Peter Hall

(1983) in the 1960s and by the mid-1980s, he could identify eight such places

as metropolises of economic and political power; Moscow

has always been on the list.� It was Friedmann (1986) that formalized the �world city concept�

by proposing a set of interrelated theses on the linkage between urbanization

and economic globalization.� These theses

incorporated capital flows, migration flows, social polarization, and political

outcomes were formalized into the world city concept later by Friedmann (1995, 43) as a synthesis � of what would otherwise

be disparate and diverging researches � into labor markets,

information technology, international migration, cultural studies,

city-building processes, industrial location, social class formation, massive

disempowerment and urban politics�.�� In Friedmann�s view, a world city should thus be a major

financial center and a focus for the headquarters of international companies

and international organizations.� To

service the decision-making functions, business producer-service facilities

must be readily available and the city is likely also to become an important

international transportation center.�

Finally, a world city must be a fairly large city with

highly-diversified functions, that certainly should

include manufacturing industry, even though it may cease to play the role of a

locomotive in regional development or to perform an urban-planning

function.� By these criteria, for

example, Washington DC

is not a world city but Moscow

seems to meet the criteria.� The general

thesis and the roster of world cities, with their hierarchical strata, were

confirmed later by the empirical work of the GaWc

group (Beaverstock, Smith and Taylor, 1999; Fossaert, 2001).

Strict criteria for world city status were

suggested by Sassen (1991, 1993) and Shakhar (1990), pointing out that a center may only qualify

provided its transnational companies and banks/financial services operate on a

global scale.�� Beaverstock

et al. (2000, 47) stress the linkages between world cities in their

determination of world city status and developments: �world cities are produced

and reproduced by what flows through

them (information, knowledge, money and cultural functions�(italics

in original).� However, unfortunately,

relatively little data are available for place-to-place flows, as most statistics

are still state-based.� In order to

examine world city functions, the GaWc group collect

data on producer services (offices, banks, law firms, accounting firms,

advertising and media functions, stock and bonds trading, and accountancy, on

migrations of low and high-skilled individuals), and engage in content analysis

of business pages in order to track the economic linkages of the world

cities.� In this paper, we replicate some

of these data-gathering exercises in order to check their argument that Moscow is now a world city.� Specifically, we gather data on banks,

producer services, airport and telephone

communications.

Until now, the GaWc

group has overlooked many aspects of the world city phenomenon, especially the

internal dynamics (governmental control, increased polarization, office park locational strategies and business area

gentrification).� All of these elements

are visible in contemporary Moscow.� O�Loughlin and Friedrich (1996) identify

additional features of world cities stressing the dual-city nature of the

phenomenon, following Mollenkopf and Castells (1991), counterposing

the �citadel� of high-rise reflective glass office buildings to the �ghetto� of

run-down housing on the outskirts of the city and in other unattractive

locations.� Social polarization is

particularly aggravated in cities with a shrinking industrial base, a trend

that is well underway in Moscow

but has effectively ended in many Western cities as services have replaced the

secondary manufacturing sector as the prime locus of most jobs.� So far, comparative studies suggest that

social polarization is relatively lower in European than in U.S. cities (see the studies in O�Loughlin and Friedrichs, 1996 and also, Wacquant,

1993).� Moscow still seems to be in the incipient stage of

social polarization as evidenced in Vendina�s paper

in this special issue.

�

Key Developments in Moscow in

the Past Decade

In

their factor analysis of corporate service complexes of 53 European cities,

Taylor and Hoyler (2000) find that Moscow fits squarely into a sub-set of East European

cities (with Warsaw, Kiev and Bucharest).�� The

corporate mix shows high levels of banking and accountancy, a feature of

Western capitalist development in the post-Communist societies.� In Fossaert�s

(2001) spatial extension of this European analysis for the world system, Moscow is again one of five cities within a �Europe in transition� zone and he concludes that, while Moscow is now integrated into the European (and by

extension) world system of cities, the economic returns to Western firms have

been small, fleeting and unpredictable.�

More than many other world cities, Moscow is differentiated from its neighboring regions (Ioffe and Nefedova, 1998).� The average income gap between Moscovites and other Russians was (late 2000) about 4 to 1

(and according to calculations of the Moscow city government, as much as 7 to 1).� Like many other capitalist countries, new and

old, regional economic disparities in Russia seem to be strengthening under contemporary

globalization (Agnew, 2000).

On the surface level, Moscow can claim to play the role of a world city.� It is obvious that the conversion of Moscow into an Informational City is an important first step on the way to the club of world cities,

the command and control centers that shape society at the turn of the

millennium. At least, on the scale of the former Soviet Union, the city is a

major business and international political center, and firms like RAO Gazprom (gas), LUKOil (oil), RAO

EES Rossii (electricity), Rostelekom

(telecommunications)� and some banks have

virtually become transnational companies, even though they are less powerful

compared with the leading Western ones.� Moscow remains Russia�s major international aviation hub with 73% of

all traffic (down from about 82% in Soviet times).� (Aviatsionno-Kosmicheskii

Spravochnik Stran SNG i Baltii, 1998/99).� One weakness preventing further economic

growth is the inadequate business service infrastructure that meets

international standards.� The improvement

of this infrastructure and promotion to the rank of a world city, holding the long-awaited

promise of substantial political and economic benefits to Russia as a whole,

lies behind the concerted effort of the state, the city and private capital in

an entrepreneurial effort described by Harvey (1989a).� Within Moscow, the three largest projects in recent years (the Manezh Squate shopping center

beside Red Square, the building of the Christ the Savior Cathedral

nearby, and the international office quarter, �Moscow City�, 4 kilometers west of the Kremlin along the Moscow river) have all involved

huge public involvement on the part of the Moscow city government.�

A free market does not exist as considerable controls and

constraints have been imposed by the municipality on the market economy as a specific Moscow vision of the public-private relationship has

evolved under the aegis of Mayor Yuri Luzhkov (Gubanov, 1999; Pagonis and Thornley,

2000).

A characteristic feature of Moscow over the last few

decades has been an unusual combination of concentrated political power (though

this dates back to Tsarist times), decision-making functions, control and� management and a

high employment rate in science on the one�

hand, and a concentration of outdated industry, including� metallurgy, weaving industry, and chemical

industries on the other (Lappo, Golz

and Treivish, 1988; Lappo,

1992).� Available statistical data show

hyper-concentration of commercial and go-between functions in the capital. (For

comparison, Moscow has 5.8% of Russia�s

population).� In 1999-2000, Moscow

companies accounted for more than 38% of all currency incomes from export of

goods and services, while the city�s production comprised only a small part of

the Russian total (5%).� Moscow

banks account for 65-80% of all foreign currency operations.� Moscow accumulated 27.8% of foreign

investments in the country between 1991-1998 and in 1998, 56% of joint ventures

registered in Russia were based in Moscow, with foreign partnerships

contributing more than 80% of them.� (All

statistics from the City of Moscow

website: www.mos.ru). Overall of 89 Russian

regions, Moscow city received 16.7%

of all investment in Russia

with another 5% going to the Moscow

region (the oblast surrounding the city) in 1998.� In contrast, St.

Petersburg received only 3% (Investitsionnye no. 39, 1999).

Further evidence of Moscow�s

primacy is readily available.� The city

accounts for 13.8% of Russian Gross Domestic Product and 28.7% of retail

turnover. In 2001, industrial output in Russia

was up 4.9% after an increase in 2000 of 9% helped by high world oil prices

(�Industrial output up 4.9%.� Moscow Times, January 21, 2002, 7).�� In the same year, more than 3000

representatives of foreign companies were officially registered in Moscow.

The capital is by far the main donor to the federal budget and provides it with

32.7% of its tax revenue; moreover, Moscow�s

contribution has considerably grown since 1993, when it reached 11%, explained

by the location of major national companies� headquarters in the city.� Per capita gross regional product of Moscow

is the largest among Russian regions� (behind Tiumen

oblast where oil production is dominant) and more than twice the national

average (Ponomarenko, 2000).� Per capita income in Moscow

in 2000 was still almost four times as much as the national average,

up from 1995-1996 when it was 3:1.�

However, the situation is

gradually changing, especially since the 1998 crisis, which stimulated export

and production of import-replacing goods in the province.� Similarly, 1998 marked

a sharp drop in production after national decline in the mid-1990s and only in

2000, was this recovered.� The crisis

also provoked a redistribution of foreign investments in favor of the

provinces: in 1996, the ratio of Moscow

in the total investment amount reached 66.0% and in 1997, 67.4%, but in 1998 it

had decreased to 48.9%.� In January-June

2000, it dropped further to 32.5%.� In

the same period, the ratio of Moscow in direct foreign investments was about

26% - much less than only three years before, though still much higher than the

capital�s ratio in population.� There has

been a continued decrease of Moscow�s

contribution of Moscow to federal

budget, although not as pronounced as the drop in the ratio of foreign

investments.

����������� In

the 1990s, the economy of Moscow

survived a period of rapid restructuring.�

At the end of the decade, the structure of employment has become much

more similar to major world metropolises than ten years before, as Moscow is progressively losing its importance as an

industrial center.� For political

reasons, the Soviet leadership did their best to keep a large working-class

population in the capital.� In the 1970s

and 1980s, economists and even the city authorities realized that it was

necessary to withdraw obsolete, polluting and labor-consuming branches of

industry from Moscow and that a certain deindustrialization had become

unavoidable.� Hence, this process was

slow but, under unregulated market

conditions after 1991, it sharply accelerated.�

By the end of the decade, non-productive functions definitely dominated

(Table 1).� At the all-Russian scale, the

specialization of Moscow (measured as ratio of employed in the given

branch to the ratio of this activity in Russia as a whole) was in research (the capital contains

more than one-third of Russians employed in this sector), banking and insurance

sphere, telecommunications, and construction works.� By the end of the decade, the re-structuring

of employment was dramatic and the cost of such rapid transformations was high,

including the crisis in the most modern, high-tech branches of industry and

declining scientific activity.�����

Table 1: Ratio of employed in Manufacturing and Non-Productive Sphere

(% of total employment)

|

Principal

Spheres of Employment

|

1990

|

1993

|

1999

|

|

Productive sphere

|

54.3

|

49.8

|

29.0

|

|

of which

Industry

|

23.8

|

21.9

|

14.3

|

|

Non-productive sphere

|

45.7

|

50.2

|

71.0

|

|

of which

Trade

|

9.8

|

12.7

|

18.0

|

|

of which

Finance and Real Estate

|

0.5

|

1.3

|

2.7

|

Sources: Balans trudovykh resursov, 1991; Balans trudovykh resursov, 1994, Adminstrativnye okruga�, 1999.

Compared with other major

cities, the analysis of structural shifts that occurred in Moscow

between 1991 and 2000 indicates that, despite the general trends, the Russian

capital lags at least 15-20 years behind the largest world cities. In terms of

the development of the sphere of business facilities, especially, Moscow

is a particular laggard (Gritsai, 1996, 1997).� At the same time, as the key node of Russia's

international relations, Moscow

increasingly looks to the major cities of the West.� For example, over the last decade, the number

of air flights linking Moscow directly with cities in the U.S. has more than

quadrupled and has reached about 40 connections a week, while with Western

European cities, flights have increased by more than one and a half times

(about 430 connections a week) (Table 2).�

By 1996, for the first time in Russian civil aviation history, the

number of passengers at the Moscow

international hub (as well as St. Petersburg�s

hub) exceeded domestic passenger numbers.�

In total, almost 8 million passengers left Moscow

for foreign destinations in 1996.�

Comparing 1997 to 1985, the numbers give a clear indication of the

reorientation of Russia.� In 1985, 86% of flights from Russia

were to other CIS (former Soviet republics) and by 1997,

this ratio was down to 34%.� In contrast,

the ratio of flights to East-Central Europe rose from 7% to 9% with the biggest

increases coming in the flights to Western Europe (up from 4% to 28%) and Asia

(up from 1.5% to 26%).� Ratios for the

other world regions (less than 1%) were unchanged.��

In the summer 2000

timetable, 978 flight connections per week (arrivals and departures) linked Moscow�s

Sheremetyevo airport with destinations in Western

Europe (Table 2).� Frankfurt,

London and Paris

(with 124 connections each), Berlin

(105) and Stockholm (88) were the

top traffic nodes.� By contrast, despite

the geographic propinquity and historical ties, only about one-third that number linked Moscow

to Eastern European cities.� Other world

regions, with the exception of the Middle East including

Israel,

maintained few connections.� Though the

traffic was lighter in the winter season, these regional ratios are maintained.1 Since international traffic is

growing rapidly year-to year (up 6.8% in 2001 � �Sheremetyevo

traffic� Moscow Times, January 21, 2002, 8), a much-needed expansion and modernization of the 1980-era airport

is planned.�

|

Table 2: Total Connections from Moscow�s Sheremetyevo Airport.

|

Destinations

|

Summer 2000

|

Winter 01-02

|

|

Western Europe

|

978

|

664

|

|

East-Central Europe

|

342

|

269

|

|

Commonwealth of Independent States

|

172

|

222

|

|

Latin America

|

22

|

4

|

|

East and South-east Asia

|

97

|

94

|

|

South Asia

|

47

|

30

|

|

Africa

|

10

|

2

|

|

Middle East-North Africa

|

54

|

70

|

|

North America

|

66

|

62

|

|

Total Foreign Destinations

|

1788

|

1417

|

|

Source:� Sheremetyevo Airport flight guides, Summer 2000 and Winter

2001-02

Another commonly used indicator of international

linkages is telephone traffic.� Though it

is possible to agree with the reservations of Beaverstock

et al. (2000) about the difficulty of

separating business from personal traffic in both telephone and air traffic,

the data clearly indicate the variable strength of Moscow�s external relationships. In 1998, telephone

traffic with the �far abroad� (beyond the borders of the former Soviet Union) reached half of total foreign traffic.� As in air travel, Germany provides the focus of the traffic with the �far

abroad�, maintaining its position from 1994 with over 10% of all calls. (Table

3)� Other western countries with strong

business and personal (through emigration) links with Moscow also predominate in the links (US, France, Italy and the UK).� Little

evidence remains of the strong economic and political links of Soviet times; of

the former Communist states, only Yugoslavia, Vietnam, the Czech Republic, Poland, Bulgaria and Hungary have more than 1% of contemporary Moscow telephone calls.�

The Russian capital finds itself increasingly incorporated into the

complicated system of interaction between the leading links of the world system

of cities (Kolossov and Vendina, 1997, Kolossov, 2000).�

Table 3: Moscow

international phone traffic, 1994 and 1998 (% of total traffic with �Far

Abroad�)

|

|

More than 10%

|

10%-5%

|

5%-3%

|

3-1%

|

1%-0.5%

|

|

1994

|

Germany, USA

|

UK, Italy,

France

|

Finland,� Austria, Switzerland, Poland

|

Turkey, Israel, Netherlands, Yugoslavia, India, Hungary, Belgium,

Spain, Bulgaria, China, Sweden, Greece, Cyprus,

Czech Republic, UAE,

Denmark.

|

Japan,� Croatia, Singapore Slovakia, Norway

|

|

�1998

|

Germany

|

USA, UK,

Italy

|

France,� Yugoslavia, Vietnam, Turkey

|

China, Israel,

Czech Republic, Poland, Switzerland, Finland, India, Netherlands, Austria,

Hungary, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Greece, Belgium, Sweden

|

Pakistan, United Arab Emirates, Syria, Denmark, Japan, Slovakia, Korea, Croatia, Iran

|

The position of Moscow is dominant in virtually all indicators of the

financial-and-banking system. In 1999, its ratio in the financial employment

sector reached 19.1%.� Of the top 50

banks in Russia in 2000 (capital measured in rubles), 18 of the

top 20 are based in Moscow (one based in Kazan held 7th position and the 20th

rank was held by a St. Petersburg bank). Altogether, 40 of the top 50 banks are

from Moscow, a clear indication of its primacy in banking

activity (300 krupeishikh,

1999, 36-48).�� Huge amounts are

accumulated in Moscow banks: by 1995, Moscow's ratio of Russia's total bank assets amounted to 83.2%.� Even the 1998 financial crisis did not shake

the monopoly of Moscow banks.� In

1999, the ratio of Moscow banks in total capital of first 50 banks remained

at 79.8%, not including the oldest and by far the largest bank of Russia � the state Sberbank

(Savings Bank), which controls the bulk of banking operations with

individuals.� The Moscow ratio reaches 87.6% if Sberbank

is included.

In recent years, Moscow

has regained the traffic it had before the August 1998 financial crash and the

international activity of Moscow

banks has increased considerably.� Now, Moscow

is attaining the status of an international financial center, at least in the

CIS financial markets.� A number of Moscow

banks stand a good chance of becoming transnational. Across the Russian

Federation, Vneshtorgbank has a tradition extensive

network and recently opened branches in Hungary, India, Italy, Cyprus, China,

the US, Turkey, Czech Republic and Switzerland. Moscow Savings Bank has opened

an office in the Netherlands.� Since 1991, many Moscow

banks have managed to establish correspondent relations with the leading banks

of the western countries and have become� members of international settlement

and information systems (SWIFT, REUTERS, etc.).�

Foreign banks are not active in advancing into Moscow's

financial markets since decisions taken by the

Russian government restrict the operations of foreign banks in Russia

for the period of transition.� The

Central Bank of Russia

confined the proportion of foreign banks in the amount of the country's banking

capital to 12%.� Most leading foreign

banks have offices in Moscow, along

with the offices of international financial institutions (World Bank, European

Bank of Reconstruction and Development, etc.), but no bank is admitted to

normal banking operations with Moscovites.�

During the immediate

post-Perestroika period (1992-1996), Moscow

acted as a go-between for Russia's

regions and advanced countries of the West.�

The lion's share of purchase-and-sale deals for primaries and other

materials were concluded in Moscow.

Various consumer items were channeled to Moscow:

its ratio in the officially registered retail turnover is many times its ratio

of the country's population and between 1992 and 1999,

it rose from 16% to 29.6% of the Russian total.�

In 1999, the capital�s ratio in the turnover of personal services

reached 28% and Moscow accounts for

41% of all purchases of foreign exchanges by individuals. Thus, within a short

time, Moscow managed to take

advantage of its favorable objective prerequisites and benefits stemming from

the position of a centralized primate city to establish, in the new capitalist

conditions, control over the huge financial and commodity flows.� Supporting the conclusions in Taylor and Hoyler (1999), Moscow�s role as an economic node between

the West and Russia was not only noticeable locally but also in other capitals of

Russia�s neighboring countries, among them, Tallinn (Estonia), Riga (Latvia),

Helsinki (Finland), Warsaw (Poland), and Kiev (Ukraine).� Of course, such a hypertrophy of Moscow�s

functions as an intermediary between Russia

and the international market, as well as its

absolute dominance at the national financial market

will weaken as the economic situation in the country becomes normalized.� Moreover, Russia�s

economy can be stable only if it is develops a balanced network of regional

metropolises. It is likely that the capital will certainly keep its unique

position for a long time (Nefedova and Treivish, 1994). By 2000, there were no visble

signs of waning dominance.���������

Moscow

Planning in a Time of Economic and Political Change

�

The master plan of Moscow's

development to 2020, adopted in 2000, tying together the social, economic and

functional problems of development, has now been succeeded by programs

envisaging priority development and renovation of its component parts.� The entrepreneurial approach as described by Harvey

(1989a), reflecting the rejection of a traditional city management strategy,

has triumphed in the Russian capital.�

But does it mean that the entrepreneurial concept� (focused on the engagement of public

capital in private real estate speculation) has been embraced?� It is hard to give an unambiguous answer to

this question.� In a bid to avoid, or at

least to minimize, undesirable competition, Moscow

is trying hard to integrate into the world economy, specifically as an Informational

City that has all the necessary

managerial, financial, information and service infrastructure.� In so doing, the Moscow

city government, following the initiative of Mayor Yuri Luzhkov,

is taking an active part in this process, seeking to establish purposefully

up-to-date business districts in specific locations (Pagonis and Thornley, 2000).�

Nearly all current ambitious projects are associated with this

public-private partnership strategy including the proposed construction of the

high-speed railroad from the center of Moscow to Sheremetyevo

airport; the business airport at Tushino; the

high-speed railroad from Moscow to St. Petersburg; a crash program of building

a commercial and cultural center in Manezhnaya Ploshchad (Manezh Square)

completed in 1997, implementation of the Moscow City Projects � a new zone of

100 story sky-scrapers, remodeling the center-city districts of Arbat and Sretenka, and

restructuring of the Kremlin island.� The

ambitious Third Motorway Ring project was mostly completed by late 2001, except

for some eastern sections including a 3 kilometer tunnel under the historical

blocks of Lefortovo.

Networks of supermarkets

and department stores, recently built in cooperation with the largest European

companies, are a recent development. �Sixteen big department stores of the Perekrestok (Cross-Road)� network, 5 Ramstores,� two�

stores of IKEA (a Swedish furniture chain), are open or under

construction.� These and other retail

initiatives have caused a retail boom.� Moscow

has just 300,000 square meters of �civilized retail space� (supermarkets,

hypermarkets, and shopping centers) but nearly

double that amount will be constructed in 2001-02 alone.� This spurt is partly generated by a growing

retail splurge by Russians (about 10% last year; incomes are rising about 9%

per year) and mostly by a renewed interest by Western companies in Russia.� (Between 1998 and 1999, the

average Moscovite�s income plummeted from $8000 to

$2800 but it has now recovered to $5970).� Since Moscow

has only 35 square meters of �civilized retail space� per resident (compared to

174 square meters in Prague, 217 in

Warsaw, 275 in London

and 398 in Paris, according to

Jones, Lang, LaSalle Consultants), there is a lot of opportunity for

growth.� Furthermore, Moscovites

spend 80% of their income on retail consumer goods (London

is 38% and Prague is 40%), with

two-thirds of this expenditure still going to kiosks and outdoor markets.� Mayor Luzhkov is

committed to converting the kiosks and outdoor markets

to indoor shopping spaces ordering 106 of the city�s 200 outdoor markets

closed by the end of 2002.�� (All figures

from Startseva, 2001).������

�The

contemporary Moscow urban planning practice is clearly aimed at

taking advantage of the benefits of linking Moscow, as the key economic center in Russia, to the world economy.� The Moscow city government is seeking access to resources

from the private sector but at the same time, the Luzhkov

authorities want to establish their control over the most profitable spheres of

the urban economy.�� This long-standing

urban planning tradition emanating from Soviet times does not allow market processes to develop spontaneously and freely

since tradition imposes substantial regulations, often used to ensure

participation of the city in economic projects or at least, in the distribution

of their results.� Whether such a policy

is justified by the need to combine the private interests of investors with

collective interests of city residents remains an open question.� Proposed projects are evaluated in terms of

�value for the city�, direct participation of the local state in implementing

many projects, and development of programs and proposals promotes the capital's

business sphere by urban planning institutions (Moskva, 2001).� Moreover, the traditions and accumulated

experience of urban planning solutions of the Communist period impede the

progress of the entrepreneurial mentality.�

There is a temptation to transform old ideas and projects to accord with

the new capitalist realities, with unexpected results.

�A

characteristic example of the new thinking is �Project Proposals for the

Development of a�

System of City Centers� (Proektnye

predlozhenia� po razvitiu sistemy

gorodskikh tsentrov)

submitted by the Moscow Master Plan Institute to the Moscow Government in May,

1996, as a concept of territorial development for business improvement

districts in Moscow.� In this document, one can see the imprint of

the old master plans and lack of a clear idea of what a business district

is.� The historic core of the city is

regarded in an undifferentiated manner; it is assumed that all of it will be

converted into a business district.� The

former centers of town (dozens of planning districts) are �assigned�

the roles of intra-urban business centers.�

Over the past few years, they have become the focal points of

spontaneous trade development, with street markets

and kiosks near Metro stations regarded as local business centers.� The draft document almost totally fails to

portray any knowledge of the contemporary peculiarities of the location and

real estate market in the city.� The inefficiency and woeful performance of

state planning institutions has given rise to a situation where their functions

have been assumed by architectural-planning or real estate companies in

coordinating diverse areas of activity, from project inception to final

implementation.� These firms can

demonstrate to the Moscow Government how expeditious their urban planning

solutions are and, at the same time, meet� growing consumer demand.

Even with state or municipal participation,

private companies do not pursue altruistic social goals, but give preference to

corporate interests. This is particularly evident in the center of Moscow where �elite�

office-cum-residence complexes are under construction. These developments

comprise a group of buildings with a complete range of residential and business

functions and a well-developed infrastructure in the form of garages, swimming

pools, gyms, security, playgrounds, etc.�

The urban environment of the center is being fragmented.� Some blocks like a series of housing-office

complexes in Sretenka (northern part of the center

city) are turning into a "packaged product", being oriented to a

particular kind of activity for a specific group of visitors-residents, who are

growing increasingly isolated in self-contained communities. Ordinary Moscovites find� themselves total strangers in these

developments and, typically, they are not admitted.� The socio-political climate in the capital is

thus quickly turning the urban environment into a source of land use

conflicts.�

Although the use of a marketing approach to city development started about 5

years ago, its strong and weak points are already obvious.� The strong points include mobilization of

various financial sources and the creative potential of urban planners for

genuine reconstruction and enhancement of city services and utilities on a

scale comparable only to the Stalinist era (1922-53).� The obvious weakness is that projects are

isolated, corporate, extremely costly, and ignorant of the social

situation.� Furthermore, the citizens of Moscow have no say in the decisions that are made.� Attempts to solve these problems using

relatively traditional methods of planning consist of pursuing a "city for

residence" policy (locating homes side by side with the offices),

entertainment facilities, prestigious residential houses, trade zones, cultural

and leisure centers intended primarily for the "day-time" population

of the city.� Such a policy is designed

to safeguard the city center from "privatization", to try to

reconstruct a functionally interrelated urban environment by linking areas

closed to the public with attractive community spaces. However, despite these

plans, the �dual city� phenomenon (Mollenkopf and Castells, 1991) is quickly being constituted in Moscow. (See also Vendina�s

article in this issue).

�

The Formation of Business

Districts in Moscow

�

The

propensity to establish areas within Moscow where offices of various producer service firms,

shops, credit-and-finance institutions, and state organizations are

concentrated, calls for a detailed street-by-street analysis of their

distribution.� Unlike most of the world

city literature, we are extending the consideration of changes to the

intra-urban character of the city.� Our

sources of information are the many and voluminous reference/informational and

advertising publications (Moscow Yellow Pages, Tsentr-Plus,

Extra-M, etc).� In the analysis of

intra-Moscow developments, we used post office codes as our territorial units

thus making it possible to link institutions in different spheres of activity

with the postal zones.� Nearly 500

post-office districts service the residential areas of the city. Where firms or

organizations functioned as part of major institutions (ministries, institutes,

enterprises, etc.) and used a departmental post-code, these were assigned a

different address according to the specific street location.�� In total, we have more than 14,000 locations.� The data are for 1996 and 2000, and are

analyzed according to the retail trade, banking/financial services, and

business services categories.

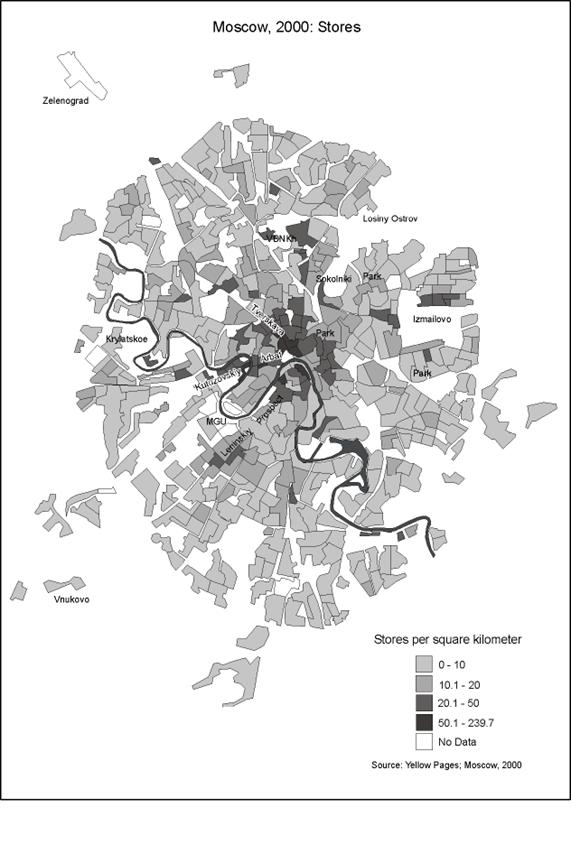

Retail Trade:� Trade, an

indicator of the eternal linkages of cities, can hardly be regarded as an

�innovative� type of activity.� For

post-Soviet Moscow, however, trade has performed an innovation role,

having assumed the function of the primary motivating force, not only of

entrepreneurial activity, but also of urban development.� Trade in general, and shop windows in

particular, generate a certain street atmosphere constituting one of the

crucial factors that form the image of a place.�

The correlation between the prestige of a place and the concentration of

the new tertiary and quaternary economy is obvious.� By and large, the spatial picture of the

distribution of shops, exceeding 7,000 in 1996 (not counting the numerous

kiosks found in all neighborhoods but clustered near the Metro stations) is

characterized by dominance of the center, where the number of street traders

and trading firms is many times greater than the outskirts.� Mayor Luzhkov is

successfully trying to upgrade the kiosks, getting rid of them as urban blight

and progressively replacing them with pavilions and shopping malls. In 2000,

there were already about 24,000 shops, and 10,600 kiosks in Moscow and the 223 surviving

street markets mainly served people with limited incomes.

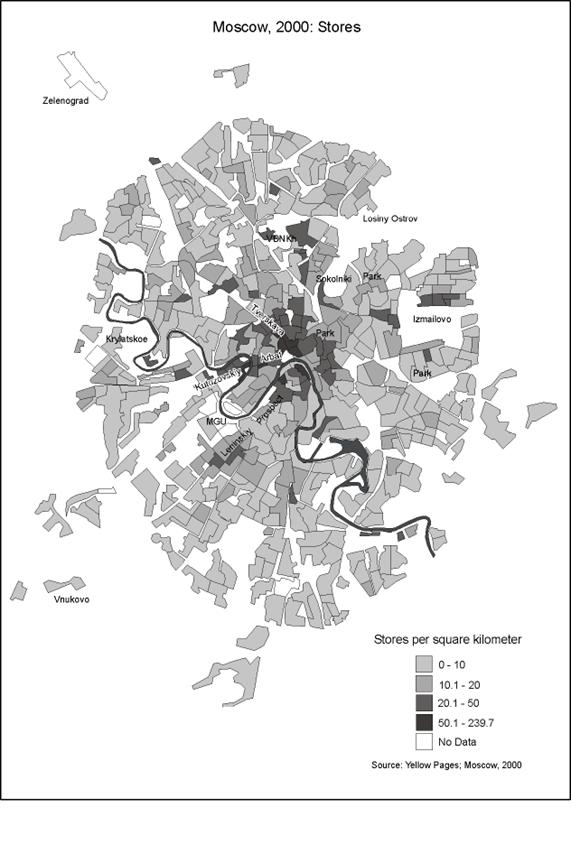

�Figure 1

- The density of stores selling non-alimentary products in 2000.� Source:�

All Moscow, 2000; advertising newspapers, 2000.

�However, the center of Moscow is far from uniform.

Within it, one can distinguish the most prestigious and the most peripheral

districts, transition districts and districts of varying specialization.� For example, the pattern of the network of shops

and firms dealing in books and stationery goods conforms to the shape of the

Boulevard and Sadovoye Rings; furniture stores

gravitate towards the north-eastern sector of Moscow's historical core. (See Figure 1).� Of

special interest is the distribution of shops dealing in luxury items, art,

antiques, and high-priced boutiques. These are true indicators of prestige and

attraction of a particular place. �Judging by the distribution of prestigious

shops, the quarters adjoining the Kremlin are most attractive, sited within the

Boulevard Ring, Tverskaya ulitsa,

Arbat and Novy Arbat with� the

neighboring sections of the nearby House of Government, the� Balchug area

(Kremlin Island), Sadovoye Ring around Bronnaya Streets, Kutuzovsky

Prospect near the Triumphal Arch and Park Pobedy, the

districts of Zamoskvorechye, Frunzenskaya

Embankment, Taganka ploshchad,� the All-Russian Exhibition Center (VVTs) and the areas around�

the Universitet and Profsoyuznaya

Metro stations.� The contrast between

these prestigious loci and peripheral territories is striking.� Nevertheless, two outer areas are worthy of

note.� Here the locational

prestige is high at present and likely to increase over time - the area near

the Airport Metro station and a rather large territory between the Akademicheskaya� and Kaluzhskaya

Metro stations, along Profsoyuznaya Street..

����������� The economic crisis of August

1998 seriously undermined the development of tertiary activities. In September

1998, at least 200,000 people employed in the new privatized sectors of the

economy lost their jobs, and salaries of others measured in US dollars usually

diminished to about one third of the pre-crisis level. Some Western companies

ceased their activity in Russia, most

often in Moscow.� Most preferred to wait for better times, and

in Moscow, they came

soon; the capital recovered much faster than in other Russian regions.� At the same time, inflation slowed down, the

industrial production and the turnover of retail trade and services started to

grow again by 1999, and positive tendencies significantly strengthened in 2000,

in economic terms, the most successful year for post-Soviet Russia.� The Moscow economy as

a whole suffered from economic losses only in 1998, losing 34.6 billion

rubles.� Already in 1999, the result was

positive (+72.5 billion rubles). As a result, ambitious projects were not

stopped.� However, incomes have not yet

reached the 1997 level, especially salaries of those who are paid from the

state budget; in January-May 2000, they had only reached 86% of the 1997

level.� Since a large proportion of

consumers could not afford expensive imported goods, it stimulated domestic

production.� In the real estate market, prices

diminished, too, especially for cheap housing.���������� �����������

Finance.� The specificity of requirements demanded for

a particular location by the finance-and-credit sphere may be determined by

analysis of the banking system, its most crucial and

sprawling industry.� In terms of the

number of commercial banks per capita of the population, Moscow is far ahead of

the provinces, with one commercial bank in the capital for every 8,900

Muscovites, six and half times the Russian average.� Muscovites are now provided with banks and

banking institutions at the level comparable to many Western countries.� In West Germany, for example, in 1990,

there was one banking institution per 9000 people.� However, as far as the diversity and quality

of facilities offered, Moscow banks still lag behind

those in the West.�� Moscow banks typically offer

about 80 kinds of services, compared to about 200 in Western banks.� One of the most serious consequences of the

1998 crisis was the crash of seven of the largest Moscow banks.

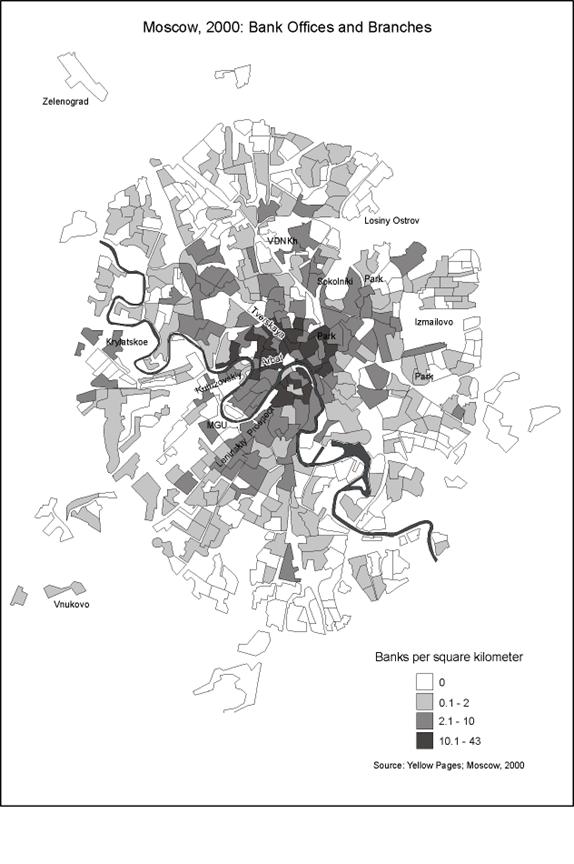

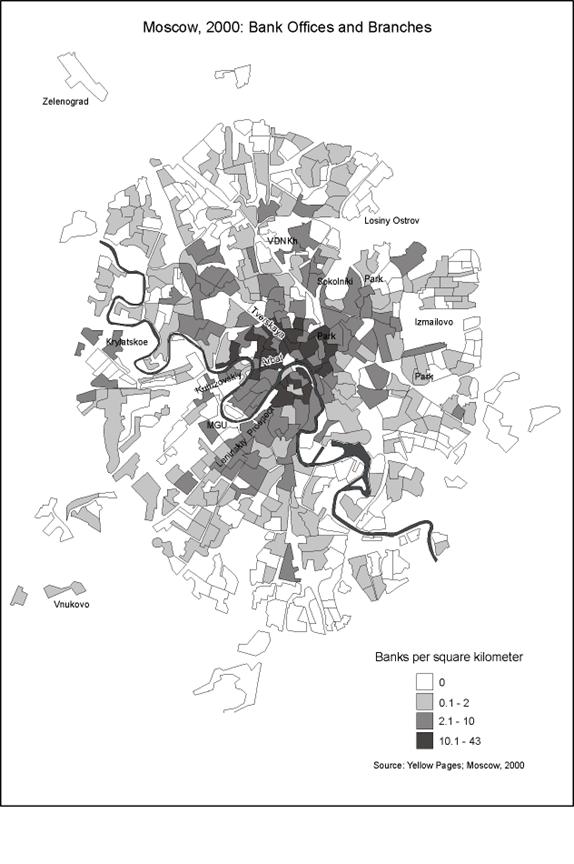

Moscow's historic core is

clearly visible as the zone of concentration and highest activity in the

banking sphere (Figure 2).� While seeking

to gain a place in the center of the city, the banks compete successfully with

other, less prosperous and powerful spheres of activity, forcing them out of

their long-standing locations. Trading and retail firms are sometimes unable to

compete for space with the banks.� There

is little doubt that it was the remodeling of old premises for bank offices

that marked the beginning of the widespread architectural

transformation of Moscow's core that we witness

today.�� Moscow�s pre-Revolutionary

heritage has had a notable effect upon the accommodation of banks.� Nearly all former bank buildings revived

their functions, often after 70 years of Communist control.� As a rule, these buildings house the

headquarters of major commercial banks, set up with the participation of the

federal state capital.� Moreover, they

have been centers of attraction for the establishment of new banks nearby.� For example, at Kuznetsky

Most, in addition to the Head Office of the Bank of Russia, the country's major

banks, such as Vneshtorgbank of Russia, are also

located.

Figure 2 -� Main offices and branches� of Russian and foreign banks in 1996 (not

including Sberbank).�

Sources: All Moscow, 2000; advertising newspapers, 2000.

The location of �sectoral� banks, established on the basis of their

connections to state ministries and departments, almost invariably corresponds

to the location of their founders.� The

same goes for the location of some banks of large enterprises and organizations.� Usually, such banks are housed in the

buildings owned by their sponsors, and as a result, are scattered over the

city.� From mid-1994, Moscow has been an arena of

stiff competition among the numerous commercial banking institutions whose

strategy is to attract clients from different parts of the city and to cover

its entire area with a network of their branches. However, more often than not,

such facilities are aimed either at legal entities or high-income

individuals.� It is not by mere chance,

therefore, that banks seek to open their divisions and branches in the busiest

and most prestigious avenues of the city - Tverskaya ulitsa, Novi Arbat,� Sadovoye

Ring, Leninsky Prospekt,

and Prospect Mira. The network of branches proves to be very closely associated

with the head offices of the banks; the correlation coefficient is +0.67.

The unusually high

concentration of bank offices is indicative of the high prestige of particular Moscow districts, coinciding

with the districts where expensive stores are concentrated.� Along with the Boulevard Ring, Arbat, Balchug, Taganka, Petrovka and Neglinka are becoming� increasingly important as they form

one cluster together with Tverskaya.� Apart from these, new banking districts are Pokrovka Street and Pokrovsky Boulevard, the area near the Oktyabrskaya metro station, and the adjoining Yakimanka and Sadovoye Ring are

also evident. �Outside the center of

Moscow, as well as on the outskirts of the city, there also emerge notable

points of banking activity growth.� These

include Prospect Mira-Ostankino, the area around the Tulskaya Metro station, and Kutuzovsky

Prospect - especially its section around the Triumphal Arch. Additionally, a

rather sprawling district, though mixed in land-use, in the south-west of the

city, including Leninsky Prospect and Profsoyuznaya Street from Gagarin Square to the Yugo-Zapadnaya and Kaluzhskaya

Metro stations, is developing as a banking center.� As yet, none of these outlying districts can

match the center in terms of attraction or the� level of bank concentrations.�

Producer

and Business Services - Referred to as �activity to promote market development" in

the official statistics, these firms include activities that have emerged in

Russia only after 1991: real estate operations, advertising, audit,

accountancy, economic and political consulting, mediation firms of all

description (brokers, dealers), computer and telecommunication facilities,

consultants, business tourism and firms organizing business meetings and

conferences.� The list includes more

traditional, but definitely modernized spheres, such as transportation and

postal facilities, as well as education.�

The producer service

sector has grown in different ways but, above all, it exists in Moscow as a

kind of applied activity of institutions and firms that accumulate capital,

especially major banks, investment and construction companies.� Many of the firms dealing in business service

were initially set up jointly with state bodies since relations with the

�parent� organization at the outset assisted a new company to promote business

technically as well as administratively, such as in leasing an office at an

acceptable price.� Therefore, most firms

of this nature are accommodated in the buildings of the �parent� organizations.� For example, a major real estate firm is

located in the building of the Central Real Estate Exchange (Tsentralnoye buro obmena);�

numerous TV advertising agencies are located at the Ostankino

TV Center; advertising and information firms are headquartered in major

publishing houses; the four firms controlling telecommunication and computer

networks (Sovam-Teleport, Rospak,

Iasnet, Tekos) are

housed at� the Russian Academy of

Sciences� Institute of Automated Systems; and Telecom has� superseded the

USSR Ministry of Communication Means Industry.

When firms started

�from scratch�, with little initial capital, they were content to have modest

offices.� Their main suppliers were

various �lower-quality� ministries, hotels or even guest-houses, research

institutes, computer centers or educational establishments conveniently located

in the city, with an infrastructure dating back to Soviet times but offering

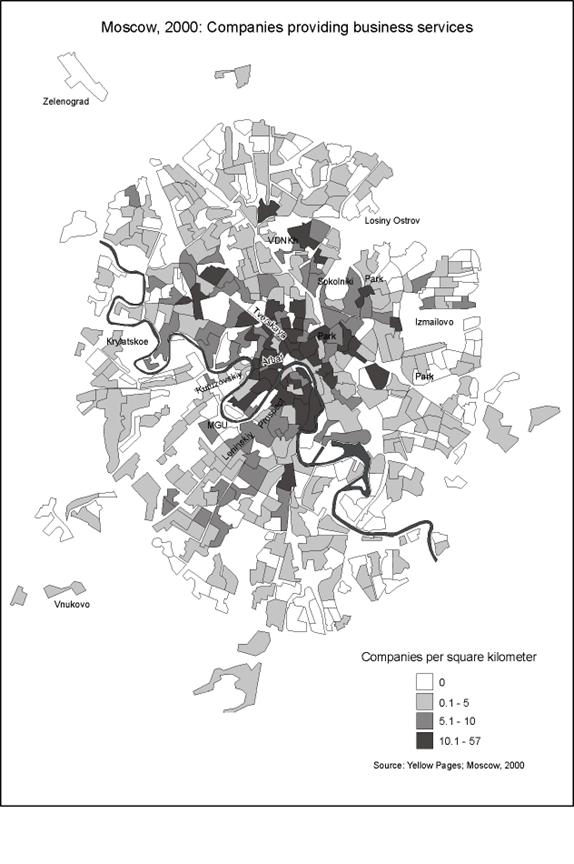

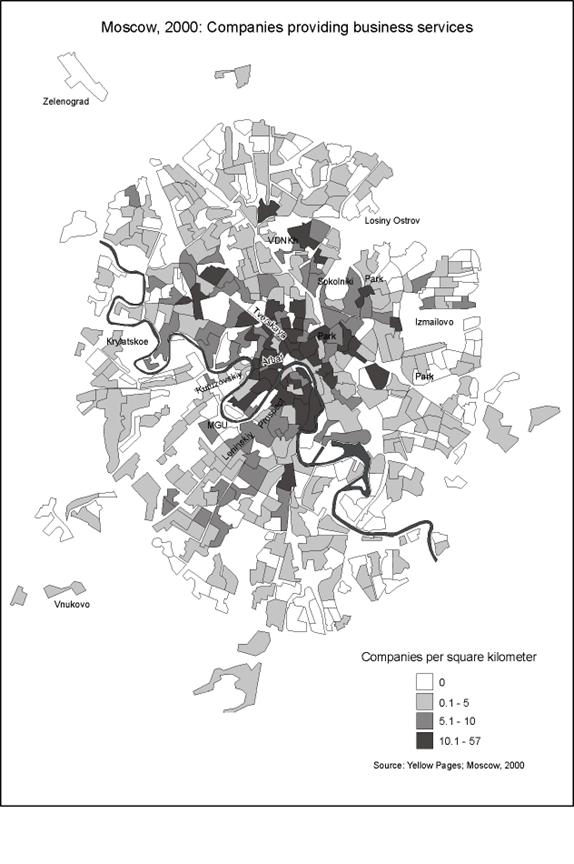

lower leasing rates.� The spatial picture

of business service location thus reveals distinct territorial preferences (see

Figure 3).� In addition to the center,

these are located in the south-western sector of the capital, which, like the

tail of a comet, stretches from the compact business core, similar to it in

terms of the density and variety of the facilities offered.� There are two reasons for such a magnetic

attraction to the south-west: first, a high concentration there of

scientific-research institutes dates from Soviet times and, second, the social

pattern of the population dominated by individuals with a higher education,

engaged in intellectual-scientific activities (Vendina, 1996). Politically, its

distinctive higher socio-economic character can be easily identified in

rayon-based maps.� (Kolossov,

1997: see also the maps of Moscow in Vendina�s

article in this special issue).�

In the December 1999 elections to the State Duma,

in central and south-western districts, Luzhkov�s

bloc �Fatherland � All Russia� won with about 40% of votes, as in Moscow as a

whole, but center and right parties � Yabloko

and� The

Union of Right Forces - received their highest support in this region and

together received more than one-quarter of the ballots.� At the same time in these districts, the

failure of President Putin�s Unity in

Moscow was especially evident: only 5-6% of electors

opted for it � less than a quarter of Putin�s support in Russia as a whole.

In other parts of the

periphery of Moscow are districts of high

business service activity, contrasting sharply to the surrounding areas of

deprivation.� Such high-profile districts

include Ostankino - VDNKh (now

VVTs), Dynamo- Aeroport and

Voikovskaya, Sokol - Oktyabrskoe Pole,�

Boris Filevskaya Street � Krylatskoe,

Krasnopresnenskaya�

Embankment - "Ulitsa 1905 goda" Metro station, Sokolniki-Preobrazhenskaya,

Semenovskaya-Izmailovskaya, Pervomaiskaya,

and Dmitrovskoe Shosse near

the 'Molodezhnaya" Hotel.

Interest in the central

part of the city as a locational magnet is not

waning, despite the fact that Moscow�s transport and

communication lines are extremely overloaded, with enormous traffic jams and Metro crowding in the center.� However recently, there have been some

attempts to build large office blocks for major companies like Gazprom (natural

gas monopoly) and Sberbank

(Savings Bank) outside the city center. �As a complementary kind of activity, business services

will almost certainly follow the leaders, further promoting and saturating the

entrepreneurial environment, creating a special business atmosphere in specific

locations near the edge of the city, a development analogous to the edge city

office parks found in Western Europe and North America (O�Loughlin, 1992).� Demand for office space far outstrips supply,

with the vacancy rate dropping to 5% at the end of 2001.� Class A office space rents for about $550 per

square meter per annum and class B office space for $400-$480 per square meter

(Ognev, 2001).����

The Geography of Business

Districts in Moscow

The business district is a compact segment of the

city, in which the state organizations, head offices of large firms (including

credit and finance institutions) are concentrated, and conditions are provided

for their successful operation in the form of a sprawling system of business

and producer services, telecommunications, and computer communications.� The attractive urban environment can be a

kind of a business district visiting card, conveying a symbolic meaning, and

provides various facilities for face-to-face contacts and meeting individual

requirements of the businessmen (restaurants, shops, cultural centers).�

One of the crucial conditions of establishing a business district is

good accessibility as well as adquate transport.

The development of a business district is a

time-consuming process.� Such districts

began to emerge late in the 19th century when most financial institutions of

Moscow were located in three main districts: (1) Kitai-Gorod,

near the Stock Exchange and Torgovye Ryady (Rows of Stalls); (2)�

Kuznetsky Most, side by side with high-priced

and fashionable stores, and (3) around Tverskoy

Boulevard.� Many buildings in these

areas, at present largely occupied by state organizations, were built specially

for the banks.� For example, in Ilyinka Street (Kitai-Gorod), Moscow�s largest banks were located.� Near Kuznetsky Most

were the oldest banking institutions of the capital and Moscow's largest private credit institutions, Junker and

Co. and� Dyamgarov Brothers.�

Also at this location was Moscow International Commercial Bank (later, United

Bank), a division of "Credit Lyonnais,� the only foreign bank allowed to operate in the

Russian Empire (Klimanov, 1997). �Naturally, the formation of a business

district was not restricted to the setting up of a series of banks.� It was no coincidence that novelties like Slavyansky Bazar, the

first Russian restaurant in the center (the rest were referred to as "traktir" or eating-houses), was set up in the 1873 in Kitai-Gorod, and the French restaurant, Hermitage, was opened near Kuznetsky Most in the 1840s (it moved in 1864 to the

Boulevard Ring).� Not far from the Hermitage, there was Zverev's

Traktir, commonly called �Bread Exchange�; here

millionaire-wholesalers who held the entire bread business in their hands congregated, and all major deals were concluded over a cup

of tea (Gilyarovsky, 1980).�

Business districts may be distinguished by the

time of establishment, maturity, and functions they perform, whether they are

multi-functional or specialized, national-international oriented.� Established existing districts are understood

as integrated and multi- functional when they feature a great abundance of

business services.� Strictly speaking, Moscow business districts cannot be taken as solid since

none of them has clearly defined boundaries, and many even lack a clear self-image.� Putative business districts are among the

conveniently located quarters that have crucial prerequisites for the

development of a complete set of business producer functions. They can take the

form of a combination, within a limited area, of large and prestigious hotel

complexes, state bodies, multi-profile trade and office buildings, and

high-quality housing.� However, they lag

behind the existing business districts in terms of the abundance of business

services. More importantly, these districts lack sufficient decision-making

loci.�

����������� As potential business districts,

locations conveniently sited at the crossing of transport routes outside the

historical part of Moscow are prime targets.� These neighborhoods have some prerequisites

for the emergence of crucial business functions already available - advanced

trade, exhibition complexes, individual business centers, headquarters of major

firms, and existing hotels.� However,

these areas are not yet compact enough, the available business facilities are

insufficient and the local urban environment remains unattractive.� To encourage further development, more

concentration is needed including the presence of one or more� decision-making centers, including

state institutions, major banks, headquarters of Russian national companies

or� international companies, and a

well-developed sector of complementary types of activity, particularly business

services. Further, a clear spatial structure is required including the presence

of a dominant business core or several centers, without which the business core

"floats in the air"�

and exists separately from the surrounding city� environment.�

In this study, as we delineated the business districts, quantitative

(density) as well as qualitative (structure) characteristics were

considered.� It is possible to

distinguish eight well-established multi-functional business districts in Moscow.� Of these,

the first four (Kitai-Gorod, Tverskaya,

Kremlin Island and Myasnitskaya) took shape during the

long process of the historical development of the city's center.�

Figure 3 - Companies providing business-services).� Sources: All Moscow, 2000; advertising newspapers, 2000.

The business districts that began to form in

Soviet times may be regarded as firmly established rather than historical.� These are not compact and their buildings are

grandiose, but the key structures stand far apart from one another, creating

accessibility problems due to inadequate city transport.� In many parts of these business districts,

the urban environment is not geared to the individual nor is it developed or

attractive enough. These four Soviet districts are located in Arbatskaya -Novi Arbat, Oktyabrskaya, Ostankinskaya, and Krasnopresnenskaya.�

The districts of the historic center of the city that are located

between the dynamically-growing business districts are acquiring a special locational advantage and it is here that prestigious

housing has started to concentrate.� The

urban environment in such quarters is being rapidly transformed, bringing in

business services and offices of small firms. These are, above all, Zamoskvorechye and the Sretenka

area of the north central city. (For gentrification

developments in Sretenka, see O�Loughlin, Kolossov

and Vendina, 1997).� Scattered

throughout the Moscow landscape in which business facilities abound,

there are numerous gaps so far impenetrable to business activity.� These are the areas where crucial centers of

the military command and of the government are located, including the General

Staff, Ministry of Defense, and major government ministries.� Bastions of the command and administrative

system in the Soviet past, the districts they command are still excluded from

the city's vital space, remaining as stern and unconquerable as ever.�

In addition to the eight existing business

districts identified above, there are five others taking shape in Moscow, with another seven potential zones in the

future.� The five developing districts

include Dinamo,� Taganskaya Ploshchad, Gagarina Square-Leninsky Prospect, Yugo-Zapadnaya,

including the Olympic Village, and Kutuzovsky

Prospect near the Triumphal Arch and Park Pobedy.� The latter may, in the long term, merge with

the existing Arbatskaya district.� The seven potential business districts (Izmailovskaya, Filevskaya, Kaluzhskaya, Frunzenskaya, Sokolniki, Universitet and Oktyabrskoe Pole metro) face a serious impediment to their

development in the unsuitability of buildings set up mostly between the 1960s

and 1980s for accommodating banks, small offices or shops.� These offices have very little potential for

new construction and have limited �image resources� due to the deterioration of

the mass produced� residential houses, of

which there are quite a few in these areas.�

Conclusion

Moscow is becoming increasingly like other world cities,

especially in the factors governing locational

choices for business services that are part of the international network of

economic activity.� Changing paradigms in

the systems of city management, a transition from plan (government)-based

methods of� management

to entrepreneurial methods, the absence of a universal vision of city

redevelopment and of clearly-formulated�

entrepreneurial strategies of the local state have all resulted in

positive and negative consequences in Moscow.� Russia's capital is faced with virtually the same

phenomena that are observed in all major Western cities that have entered the

era of an informational society.�

The adverse world city consequence for Moscow lies in the rapid and basically unplanned growth of� superstructure

functions� -management, high-order

facilities, trade in exclusive items, and elite housing.� In contrast, basic functions (production,

housing, and transport) are quickly declining. The current reconstruction in

the capital involves a limited number of urban districts, while most

neighborhoods lie neglected. Above all, the historic center of Moscow has captured nearly 40% of capital investments

and construction, although it accounts for only 6.4% of the total city area and

its population does not exceed 8%.� We

can expect further depopulation of the center, if the experience of central

city neighborhoods is typical (O�Loughlin, Kolossov and Vendina, 1997; Pavlovskaya and Hanson, 2001).�� A characteristic opinion is that of Moscow's

chief architect: "Administration in the city center must be represented by

organizations of the federal level, trade must only be available in the form of

leisure, as a big signboard for all to see rather than a� street with shops; all housing should be in

the attics" (Domnysheva, 1996). The new business

and political elite have expropriated the rehabilitated areas of center and

this course of development is leading to the establishment of a �super-city�

within Moscow.� This

�dual city� is remaking the center as totally different by its contents in the

form of higher-order functions, but it also is acquiring a new post-Soviet

look.�

The positive results of world-citification consist

in the provision of new services and utilities, the building of an attractive

image of the city in the world-economy, a growing variety of architectural

forms that are completely different from the mediocre Soviet stereotypes, and

the growing diversified services aimed at accommodating both individuals and

businesses.�� The main problem of the new

emerging strategy of urban development is to combine the tasks of attracting

investors and improving the investment climate with the social programs,