Introduction:

�Moscow � Post-Soviet Developments and Challenges�[1]

John O�Loughlin* and Vladimir Kolossov**

*University of Colorado, Boulder

** Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow

Russia

has always been a highly centralized state, with the capital playing an

exceptional economic, social, cultural and political role.� Paradoxically, the post-Soviet economic

transition not only did not reduce this primacy, but on the contrary,

considerably strengthen Moscow�s

hypertrophy.� During the 1990s, political

events in the capital (attempted coups d�etat in 1991 and 1993, the struggle between �reformers� and left-wingers) decided the destiny of

all Russia,

with most regions only observing with anxiety.�

Though its ratio of Russia�s

total population is just less than 6%, the city contains more than half of all

banking activity, more than one-fifth of retail trade, and one-third of

wholesale trade.� Moscow

has, to a large extent, monopolized the functions of a mediator between the

country and the world economy and has become by far the most important national

node of financial flows.� Even if the

August 1998 financial crisis contributed to a certain improvement of the

balance between the capital and the provinces, Moscow

remains the major �exporter� of Russia�s

primary exports (oil, gas, timber, gold, etc.)��

It is being transformed into a true global city (Gritsai 1996, 1997;

Taylor 2000).

The average per capita income in Moscow is much higher than in any

other of the 88 regions in Russia, and

more than twice as high as the second-highest, St. Petersburg.�� Moscow provides an example of post-Communist economic restructuring to the

whole country and now contains the most sizeable new middle class.� The streetscape of the capital has

considerably changed during the last decade.�

In its downtown, contemporary offices are mushrooming, and historical

buildings look fresh after recent renovation by private investors; at night, Moscow�s main avenues are brightly illuminated by shining shop windows and

advertising by global companies, provoking sharp envy from residents of many

other Russian cities, which remain dark and suffer from municipal debts and

power shortages.� Is Moscow really the dominant player in the Russian economy, determining the

orientation and the rates of national restructuring? How stable is the Moscow�s �miracle�?� What is the

reverse side of the coin, the inequities and polarization that has become

apparent in the past decade?� These

questions are increasingly at the center of discussions among politicians and academic

specialists.

The economic and social costs of Moscow�s rapid changes since 1991 are already clear.� Moscow has definitely became a demographic

�black hole�: mortality has exceeded fertility for a decade, the city�s

population is getting older and the decrease is compensated only by labor

migration from most of the former Soviet republics, from other Russian

regions, and even from some third world countries.� Most migrants live in Moscow illegally.� These processes

worsen the qualitative composition of population, create tensions in the labor

and housing markets, and can potentially lead to ethnic and religious conflicts (see

Vendina�s article in this issue).� Though

the social territorial differentiation in Moscow has not yet reached the scale of U.S. or even West European cities, the growing social polarization has

already seen the creation of �gated communities� and can condemn the great

majority of Muscovites to live in neglected and forgotten housing ghettos.� Moreover, this polarization process risks

perpetuating social contrasts in creating multi-standard systems of education

and health care � separately for the richer and the poorer strata of

society.�������

Moscow city authorities must solve other aggravations.� One of the most serious, requiring huge investments, is the housing problem, specifically the

reconstruction of the physically obsolete and dilapidated part of the housing

stock, four-story apartment blocs (Khrushchoby) built in the 1960s.� Moreover, the city lacks empty spaces for new

developments and, thus, it is necessary to demolish old residential and

industrial buildings or to shift industrial plants in order to intensify land

uses.� Another urgent problem is rapid

automobilization, related to the insufficient capacity of the roads� network

and of parking; constant traffic jams already render downtown Moscow inaccessible by car on workdays.�

(See the paper in this issue by Bityukova and Argenbright on the

pollution effects of the growth in car ownership).� Against this background, slow development of

public transportation caused by inadequate investment seems to be especially

pressing.� The city government does not

possess the financial means to build highways such as the Third Ring and, at the

same time, to invest in extending the Metro (subway) and other public

transportation.� The city authorities under the leadership of Yuri Luzhkov (mayor since 1992)

has pledged to continue to invest in prestigious projects to maintain Moscow�s image and competitiveness as the Russian capital and a new global

city.

Like any major city, Moscow has a complex structure that needs to be considered at different

levels.� First, at the global and

macro-regional (Central-East European) scale, Moscow�s relations are dominantly economic as part of a world-city system

(Taylor and Hoyler, 2000).� Second, at

the national scale, Moscow is both the federal capital and a subject of the Russian Federation � here the emphasis is on its primacy and balancing of the

differentiation that is becoming more apparent in the country.� Third, at the regional scale, Moscow�s agglomeration

over-reaches the capital�s city limits and issues about industrial re-location,

regional transport, city-suburb relations, and the conversion of agricultural

and forest zones to urban uses dominate.�

Fourth, at the city scale, the optimal combination that allows the city

to assume its functions, to be competitive at the international scene while

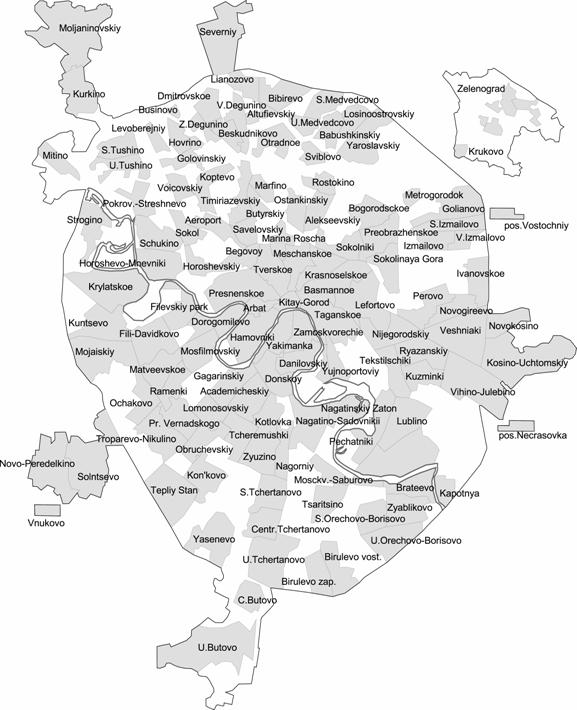

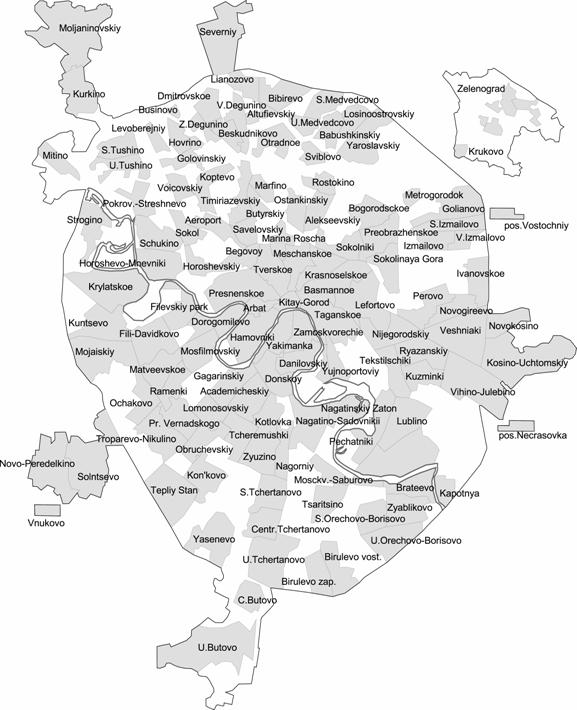

still meeting the needs of its population is still to be found.� Finally, at the local (neighborhood) scale, Moscow is a relatively vast and heterogenous territorial unit, including

124 municipal districts (rayoni) (see Figure 1), which will soon become

true local governments possessing not only their elected assemblies, but also

their own budgets.� Geographical

distributions of housing, jobs, services, green spaces, etc. across these rayoni are likely to become more

contentious and prominent.���������������

To cope with the myriad of problems across a variety of scales, the

city authorities need a long-term strategy.�

Obviously, the privileged 1990s situation of the capital can change

rapidly, as the turmoil that occurred after the financial crisis of August 1998

showed.� The Russian federal government

refuses to cover even a small part of Moscow�s expenses as the national capital. Some large companies (important

taxpayers) have already moved their registered headquarters out from the city,

and during the last two years city officials complain that the city budget is

becoming very tight.�� Discussions about Moscow�s economic future can be summarized as the choice between different

models of development that depend in turn on the model followed by Russia as a whole. If Russia remains a dominant

exporter of fuel and other raw materials and her manufacturing industry and

high-tech industries decline further, there will obviously be much less

opportunity for Moscow to realize its potential for innovation and to select a

new, more balanced model of development.�

Simplifying, one can say that future of Moscow can be based on one of three options � a) traditional manufacturing;

b) a service economy - mainly banking and trade, and c) science, information

processing and high tech industry.� In

other words, Moscow can develop as the capital of an open economy, thus continuing

current trends, or as the center of national modernization.� Before the collapse of the Soviet Union, more than

one million people in Moscow were engaged�

in pure and applied research (one-quarter of all Soviet

scholars). Though this unique human capital is now considerably weakened, the

Russian capital still ranks second among European cities by the number of

citations in academic journals and monographs, thanks mainly to the

sciences.� To ensure a sustainable

development, the city should promote these scientific innovation activities and

extend them into high-tech manufacturing (Pchelintsev, 1999).���

The authors of this special issue offer no solutions for the problems

that Moscow is now facing.� Rather, they

analyze recent data showing the post-Soviet evolution of economic functions and

social-territorial structures of the city from a perspective of its

transformation into a global city.�

Radical shifts in the economic structure of the capital changed (but did

not diminish) its impact on the urban environment.� The theme of the changing sources of Moscow�s environmental pollution (from stationary to automobiles) is

developed in the paper by Viktoria Bityukova and Robert Argenbright.� Olga Vendina devotes her article to social

geographical developments among Moscow�s ethnic minorities and the related issue of growing ghettoization.� Elena

Shomina, Vladimir Kolossov and Viktoria Shukhat analyze local community groups

(non-governmental organizations) in Moscow as responses to changing neighborhood, especially housing

conditions.� In the first paper in this

special issue, Vladimir Kolossov, Olga Vendina and John O�Loughlin examine the evidence for Moscow�s claim to world-city status and the geography of business

developments in the city since the end of the Soviet Union.�

Soviet and

Post-Soviet Research on Moscow.

Moscow

attracted the attention of Soviet geographers who began to study the unique

problems of the capital at the end of World War II.� Human geographers were especially interested

in studying the interaction between the capital and its region, and its impact

on surrounding territories of Central Russia.� They delimited Moscow�s

influence according to different criteria - the radius of daily and weekly

cycles of activity, the number of second residences, etc.; the distribution of

built-up areas, industry, services and recreational functions by sectors around

the city by comparison to their environmental impact.� The fundamental volume on these themes � Moscow�s Capital Region- the Territories,

Structures, and Environment - written by a large group from the Institute

of Geography of the Soviet (now Russian) Academy of Sciences, include

interesting chapters that serve as a benchmark

for the post-Soviet developments (Lappo, Goltz and Treivish 1988).�

Geographers gave much less attention to Moscow

itself.� The social-territorial structure

of the city was hardly examined � partly because of the lack of reliable

statistical data for micro-districts.�

The problems of Moscow�s

development were analyzed mainly by architects and urban planners, especially

those serving at the Institute of Moscow�s

General Plan, whose reports are unavailable.

Some general works containing detailed information on urban life are

available according to the respective periods. In particular, Yulian G. Saushkin, a patriarch of Soviet human geography and former

chair of the Department of Human Geography of the USSR at Moscow State

University, produced three books on Moscow (the last one appearing soon after

his death with his former graduate student, Vera Glushkova) (Saushkin 1950,

1964, Saushkin and Glushkova 1983).� In

the late 1970s�early 1980s, new geographical approaches to the study of the

local urban environment, the conditions of life and the functional organization

of the municipal economy were developed, in particular, in a laboratory of the

Institute of Geography founded by Yuri Medvedkov (now at Ohio State

University).� Contemporary quantitative

methods (especially factorial ecology) were applied in the estimation of the

quality of the urban environment (Barbash and Gutnov 1980; Barbash 1982)

Examining patterns of distribution of residential areas and jobs, the number of

requests to move into a specific area, its proximity to major transportation

lines, the convenience of transport connections, the presence of city-wide

services, the variety of employment opportunities, and the ecological situation

was used as measures of attractiveness (Barbash 1984, Vasiliev and Privalova

1984).� In the 1990s, a similar approach

was used by Sidorov (1992).

In the post-Soviet period, the

transition to the market economy challenged

geographers and other social scientists with new theoretical and policy

problems: economic restructuring, the development of the privatized housing market,

social polarization, unemployment, and old and new social pathologies all came

to the forefront of research.� Despite

publication of a number of innovative works, it is hardly possible to conclude

that Russian human geographers met these challenges.� However, the works of Vera Glushkova should

be mentioned.� She published a monograph

devoted to the dynamics and the composition of Moscow�s population, the

functions of the city and main branches of its economy, land-use and social

problems (in particular, its religious geography)� (Glushkova 1997, 1999).� Glushkova also was one of the initiators and

main authors of large, well- documented, illustrated volumes on history,

geography and urbanism in Moscow

(see, for instance, Kuzmin 2000, etc.). The second edition of the Encyclopaedia

�Moscow� is especially worth of

notice (Moskva, 1997).� Relevant

geographical information on the development of Moscow

is also contained in key historical publications (Vinogradov 1997, Gorinov 1996,

1997).�

����������� A series

of works on urbanism and architecture richly illustrated by detailed maps

of� the environment, roads,

transportation, planning structure and functional zoning of the city appeared

as a result of public discussions, the first steps in the discussion and

adoption of the new General Plan of Moscow to 2020 (Arkhitectura... 1999,

Moskva... 2000, Moskva..., 2001).� Comprehenisve studies on the history of architecture and

urbanism in the capital also appeared during the first post-Soviet decade

(Kudriavtsev, 1994).�� Geographers participated� during

the 1990s in several important works on the environment in Moscow.� In particular, Viktoria Bityukova wrote a

thesis, where she studied both the �real� spatial distribution of polluters and

their distribution by administrative-territorial units (Moskva... 1995;

Bityukova 1996; Kuzmin 2000).� Some

environmental maps can be found on the official web-site of the government of Moscow

(www.mos.ru).

Geographical studies of Moscow

were given further impetus by the improvement of official statistics, as well

as by the 1995 decision of the capital�s government to introduce a new

instructional discipline in the city�s and region�s high schools� � �knowledge of Moscow� (�moskvovedenie�).� This educational policy spurred the

appearance of a series of textbooks (for example, Alekseev et al., 1996, 1997).� Furthermore, the city government of Moscow

initiated the publication of two monthly journals that contain the results of

social studies of the city (Simptom and Puls).� The Committee on Telecommunications and Mass

Media of the Government of Moscow yearly publishes about a dozen small books on

current social problems, but unfortunately, only

a very limited number of copies are printed and are not available in most

libraries.��

Outside of Russia, in his key work, Timothy Colton (1995) analyzed the dynamics of the

city�s boundaries, and its demographic, industrial and even political patterns

in Moscow in the 20th century. Many academic journals, including Post-Soviet

Geography and Economy, regularly publish papers on the human geography of

the Russian capital.� GeoJournal

prepared a special issue on Moscow and St.

Petersburg (Gdaniec, 1997; Kolossov, 1997; Vendina, 1997).� In the field of social geography, Mozolin

(1994) explained the intra-urban distribution of housing prices in terms of

accessibility to the CBD and urban morphology.�

Bater (1994) and Daniell and Struyk (1994) analyzed the development of

the housing market in Moscow and, in particular, the results of privatization of

housing, the implementation of municipal housing programs under new conditions,

and the construction of new one-family cottages by �new Russians�. Kirsanova

(1996) widely used the results of the polls about evaluations and preferences

of different parts of Moscow by Muscovites and analyzed their relations with the gender, age,

education, and the place of socialization of respondents and with the types of

housing.� Vendina (1994, 1995, 1996,

1997), and Vendina and Kolossov (1996) related the transformations of functions

and employment in different districts of Moscow in the post-socialist years

with the pattern of housing prices on the secondary market, while

Gritsai (1997) compared the first results of market

transformations in Moscow, especially the development of business services,

with the situation in some largest world metropolises.

Post-Soviet developments in Moscow of demographic and social indicators (natural population change,

ethnic composition and the level of education, especially during the 1979-1989

intercensal period in the old administrative districts abolished in 1992), were

examined by Rowland (1992). Differences between the inner and the outer zones

of the city and the concentration of the educated people in the center and the

south-west were also considered in the analysis of the�� outcomes of the first democratic elections

in the capital (Berezkin et al., 1990

and Colton, 1995).� Bater, Degtyarev and

Amelin (1995) and Kolossov (1996, 1997) showed that the voting behavior of

Muscovites differs greatly from most other regions of the country and has

stable territorial patterns, while the differences in electoral preferences

between the west and south-west parts of the city with the remainder were

defined and explained by O�Loughlin, Kolossov and Vendina, 1997. �More recently, Pavlovskaya and Hanson (2001)

reported on the effects on family life of changes in the retail structure and

privatization of services in a rayon in central Moscow and Argenbright (2000) paints an evocative picture of the changing

nature of Moscow�s public spaces, from controlled Soviet to the contemporary

free-for-all.

Conclusion

A visitor to Soviet Moscow would hardly recognize its

successor.� The center of Moscow

increasingly looks like a Central European city, like Warsaw

or Budapest, with expensive stores,

gallerias, supermarkets, commercial offices,

and a full array of retail services.�

Meanwhile, the streetscapes of Moscow�s

outer zones are hardly changed from Soviet times.� As a small segment of the population of �new

Russians� prosper in these times of frantic change, the majority of Moscovites

struggle to make ends meet.� In a sample

of 3,500 Moscovites in April 2000, we found that only 22.8% agreed with the statement that �things are not

so bad, and it is possible to live�, while the majority (55.3%) said that �life

is difficult but it�s possible to endure�.�

Another 13.3% said that �our condition makes it impossible to endure

further.�� And, it is worth

re-emphasizing that Moscow is much

wealthier than the rest of the country and should not be considered as a

typical Russian city or even a harbinger of things to come for other large

cities of the former Soviet Union.

����������� The

frenetic pace of commercial life in central Moscow

and the associated rush to gentrification and re-development, quick money,

criminal activity, banking and financial scandals, and great uncertainties has

produced an �city on the make� (Spector,

1997).�

What is most startling is the contrast of these world-city functions and

consequences to the daily lives of most of the population.� The �dual city hypothesis� of Mollenkopf and

Castells (1991), developed for New York City,

seems increasingly apropos for Moscow.� Of course, dramatic polarization is a

persistent feature of many major Third World capitals

but its appearance in Moscow is

undoubtedly the quickest.� Whether the

growing gaps in Moscow� - between rich

and poor, between the segments of the population who are tied to the

incorporation into the global economy and those whose livelihood is connected

to state services or to small-scale local enterprise, and between the older

generation whose world is still colored by their Soviet-era experiences and the

post-Soviet generation � will magnify as they have for the past decade or will

be eased is an important research question, not only for Moscovites and

Russians, but for all societies undergoing rapid social and economic change in

these globalized times.� The papers in

this special issue contribute to this research and offer a picture of the city

after 10 years of post-Soviet change against which future developments can be

compared.

References

Alekseev, Alexander I., ed. (1996) Moskvovedenie

(Moscow Studies). Moscow.: Ekopros.

Alekseev, Alexander I., Vera G. Glushkova and Galina Y. Lisenkova, eds. Geografia

Moskvy i Moskovskoi oblasti (Geography

of Moscow

and of the Moscow Region). Moscow: Moskovskie Uchebniki, 1997.

Argenbright, Robert �Remaking

Moscow: New Places, New Selves." Geographical

Review 89(1): 1-22, January, 1999.

�����������

Arkhitektura,

stroitelstvo, disain (Architecture,

Construction Works and Design).� Special Issue on the General Plan of Moscow

to 2020, 4 (14), 1999.

Barbash, Natalia B. �Spatial Relations Among

Places with Complementary Functions Within the City of Moscow.� Soviet

Geography: Review and Translation, 23, 2: 77-94, February, 1982.

Barbash, Natalia B. �Privlekatelnost

Razlichnykh Chastei Gorodskoi Sredy Dlia Gorozhan (Na Osnove Dannykh Obmena Zhiliem)� (The Attractivity of Different Parts of the Urban Environment

for Residents (on the Basis of Data on Residential Exchange)� Izvestia Akademii Nauk SSSR: Seriya Ggeograficheskaya 5: 81-91, 1984.

Barbash, Natalia B. and Aleksei E. Gutnov �Urban Planning Aspects of the Spatial Organization

of Moscow: An Application

of Factorial Ecology.� Soviet Geography: Review and Translation, 21,

9: 557-574, November, 1980.

Bater,

James H. �Housing Developments in Moscow

in the 1990s�. �Post-Soviet

Geography, 35, 6:

309-328, June, 1994.

Bater,

James H., Andrei A. Degtyarev, and Vladimir N. Amelin. ��Politics in Moscow: Local Issues,

Areas and Governance.�� Political Geography, 14, 8:

665-687, November, 1995.

Berezkin, Andrei V.,

Vladimir A. Kolossov, Marianna Pavlovskaya, Nicolai Petrov and Leonid Smirniagin. �The Geography of the 1989 Elections of People's

Deputies of the USSR (Preliminary Results).� Soviet Geography, 30, 8:

607-634, October 1989.�������

Bityukova, Viktoria R. Sotsialno-ekologicheskie

problemy razvitia gorodskikh territorii (na primere

Moskvy) (Social-Environmental Problems of Urban

Territories� Development: the Case of Moscow) Doctoral thesis. �Moscow: Department of

Geography, Moscow State University, 1996.

Colton, Timothy S.� Moscow: Governing the

Socialist Metropolis. Cambridge, MA:� Harvard University Press, 1995.

Daniell, Jennifer and

Ray Struyk, Housing

Privatization in Moscow: Who Privatizes and Why.� Cambridge, MA: Blackwell

Publishers, 1994.

Federov, Dmitri �Telecommunication Computer Networks in Moscow.� Geojournal , 42,4: 433-448, August 1997.

Gdaniec, C. �Reconstruction

in Moscow�s Historic

Centre: Conservation, Planning and Finance Strategies- the Example of the Ostozhenka District.� Geojournal, 42, 4: 365-376,

August 1997.

Glushkova, Vera G. Moskva. Istoria i Geografia (Moscow: History and

Geography). Moscow: Mir

Publishers, 1997.

Glushkova, Vera G. Sotsialnyi Portret Moskvy na

Poroge XXI Veka (A Social

Portrait of Moscow at the Eve of the XXI Century). Moscow: Mysl Publishers, 1999.��

Gorinov, Mikhail M.,

ed. Istoria Moskvy

(History

of Moscow), vol.

1-4.� Moscow: AOL, 1996,

1997.

Gritsai, Olga �Postindustrialnye Sdvigi v Moskve: Kontseptsia Mirovykh Gorodov i Perestroika Ekonomicheskoi Struktury �

(The Post-Industrial Shifts in Moscow: the Concept of

the World City and Economic

Restructuring). Izvestia RAN, Seria Geograficheskaya 5: 90-97, 1996.

Gritsai, Olga �Business

Services and Restructuring of Urban Space in Moscow.� Geojournal, 42, 4:349-363, August 1997.

Gritsai, Olga �Moscow under Globalization and Transition: Paths of Economic Restructuring.� Urban Geography, 18, 2:

155-165, 1997.

Kirsanova 1996

Kolossov, Vladimir �Political Polarization at the National

and the Intra-Urban Levels:� The Role of Moscow in Russian

Politics and Socio-Political Cleavages within the City,� GeoJournal,

42, 4: 385-401, August, 1997.

Kolossov, Vladimir et Olga Vendina � Moscou, Retour a la Voie Mondiale. � Geographie

et Culture, Metropolisation et Politique. Ed. Paul Claval and Andr�-Louis

Sanguin. Paris: L�Harmattan,

1997: 137-153

Kolossov, Vladimir, Olga Vendina, Nadezhda Borodulina, Elena Seredina, and Dmitri Fedorov �Kontseptsia Informationnogo Goroda i Sozdanie

Novoi Delovoi sredy v Moskve (The Concept of

the Informational City and Formation

of a New Business Environment in Moscow).� Izvestia RAN, Seria Geograficheskaya, 5: 141-156, 1998.

Kudriavtsev, Mikhail P.,

ed. Moskva � Tretii

Rim: Istoriko-Gradostroitelnoye Issledovanie. (Moscow � the Third Rome. A Historical-Urban Study). Moscow: SOL, 1994.

Kuzmin, Alexander V.,

ed. Gradostroitelstvo Moskvy. 90-e Gody

XX Veka (Urbanism in Moscow. The 1990s). Moscow: Moskovskie Uchebniki i Kartolitografia, 2000.

Lappo, Georgi M., Golz, Grigori A., and Treivish, Andrei I., eds. Mosckovskii Stolichnyi

Region: Territorialnaya Struktura

i Okuzhayushchaya Sreda (Moscow Capital Region:

the Territorial Structure and Environment). Moscow: Institute of Geography of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, 1988.

Mollenkopf,

John and Manuel Castells. Dual City: Urban Restructuring in New York. New York: Russell Sage

Foundation, 1991.

Moskva i mockvichi: v kakoi okruzhayushchei srede my zhivem? (Moscow and Moscovites: In What Environment Do We Live?) Moscow: Institute of

the Moscow General Plan, 1995.

Moskva (Encyclopaedia of Moscow). Moscow: Rossiiskaya Entsiklopedia, 1997.

Moskva: Vzgliad v Tretie Tysyacheletie (Novyi Generalnyi Plan Razvitia i Ego Realizatsia) (Moscow: A View into

the Third Millenium: the New General Plan of

Development and Its Realization). Arkhitektura i stroitelstvo

Moskvy (Architecture and Construction Works in Moscow),

special issue, 5-6, 2001.�

Moskva

2000 (Moskovskii spravochnik). (Moscow 2000: A

Moscow Reference

Book). Moscow: Golden Be,

2000.

Mozolin, Mikhail. �The Geography

of Housing Values in the Transformation to a Market Economy: A Case Study of Moscow.�� Urban Geography, 15, 2: 107-127, March 1994.

O�Loughlin, John, Vladimir

Kolossov and Olga Vendina �The Electoral

Geographies of a Polarizing City: Moscow, 1993-1995� Post-Soviet

Geography and Economics, 38, 10: 567-600, December 1997.

Pavlovskaya,

Marianna and Susan Hanson. �Privatization

of the Urban Fabric: Gender and Local Geographies of Transition in Downtown Moscow.� Urban Geography, 22, 1: 4-28,

January 2001.

Pchelintsev, Oleg S. �Moskva i Strategicheskoe

Izmerenie Rossiiskikh

Reform� (Moscow and the

Strategic Dimension of Russian Reforms)� Moskva na Fone Rossii i

Mira: Problemy i Protivorechia Otnoshenii Stolitsy v Kontekste Rynochnoi Transformatsii

(Moscow Against the Background of Russia and the World: Problems and

Contradictions of the Capital�s Relations on the Context of Reforms). Leonid Vardomsky and Vladimir Mironov, eds. �Moscow:

Institute for International Economic and Political Studies and Institute of

Geography of the Russian Academy of Science, �1999, pp. 13-31.

Rowland, Richard �Selected Urban Population Characteristics of Moscow.�� Post-Soviet Geography, 33, 2: 569-590, March 1992.

Saushkin, Yulian G. Moskva (Moscow). Moscow: Geografgiz, 1950.

Saushkin, Yulian G. Moskva. Geograficheskaya Kharakteristika (Moscow: A Geographical

Characteristic). Moscow: Geografgiz, 1964.

Saushkin, Yulian G., and Vera G. Glushkova� Moskva Sredi Gorodov Mira (Moscow among the

Cities of the World). �Moscow: Mysl Publishers, 1983.

Sidorov, Dmitri �Variations in Perceived Level of Prestige of

Residential Areas in the Former USSR.� Urban

Geography, 13,4: 355-373, July-August, 1992.

Stadelbauer, J�rg.� �Moskau. Post-sozialistische Megastadt im Transformationsprozess.�

�Geographische Rundschau, 48,

2: 113-120, February 1996.

Spector, Michael. �Moscow on the make.� New York Times Magazine, June 1, 1997.

Taylor, Peter J. �World Cities and Territorial States under

Conditions of Contemporary Globalization.� Political Geography, 19, 1: 5-32, January 2000.

Taylor, Peter J. and Mark Hoyler. �The Spatial Order of

European Cities under Conditions of Contemporary Globalization.� Tidjschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 91, 2: 176-189, May 2000

Vasiliev,

Georgi L., and Olga L. Privalova

�A

Social-Geographical Evaluation of Differences within a City.� Soviet

Geography: Review and Translations, 25, 7: �488-496, September 1984.

Vendina, Olga � Moscou:�

En� Recherche� d'Equilibre�

Entre� la Planification et

Laisser-Faire � Planification et Strat�gies de D�veloppement dans les

Capitales Europ�ennes. Christian Vandermotten, ed. Bruxelles: Universite

Libre de Bruxelles, 1994, pp. 273-285.

Vendina, Olga � Moscou: les R�les de la Ville et sa Gen�se�, G�ographie

et Cultures,� 14: 85-103,

1995.

Vendina, Olga �Sotsialnaya Stratifikatsia v Moskve: Tsena Ekonomicheskikh Reform�

(The Social Stratification in Moscow: the Cost of

Economic Reform). Izvestia RAN, �Seria

Geograficheskaya, 5: 98-113, 1996.

Vendina, Olga �Transformation Processes in Moscow and Intra-Urban

Stratification of Population.� Geojournal �42,4:341-347,

August 1997.

Vendina, Olga and Vladimir Kolossov. �Sotsialnaya Polarisatsia i Politicheskoe Povedenie Moskvichei� (The Social

Polarization and the Political Behavior of Moscovites).

Sociological Journal, 3, 4: 164-176, 1996.

Vinogradov, Vladimir, ed. Moskva - 850 let. Istoria Moskvy �(Moscow - 850 years. History of Moscow). Moscow: Moskovskie uchebniki (2 vols), 1996-1997.

*Yablokov, Aleksei

V., ed. O Sostoyanii Okruzhayushchei

Sredy g. Moskvy v 1992 g. Gosudarstvennyi Doklad (About

the State of Environment in Moscow in 1992 - The State Report). Moscow: Government of Moscow, 1993.

Figure

1 Location of Rayoni in Moscow