Democratic Values in a Globalizing World:

A Multilevel Analysis of Geographic

Contexts.[1]

John O�Loughlin

Institute of Behavioral Science

Department of Geography

Campus

Boulder, Co.�

80309-0487

Email:

johno@colorado.edu

Abstract

Geographers contend that regional and national contexts

are important mediating and controlling influences on globalization

processes.� However, to reach this

conclusion, geographers have been forced to engage in rather convoluted

statistical manipulations to try to isolate the so-called "geographic

factor".� Recent developments in

multilevel statistical modeling offer a more precise and suitable methodology

for examination of contextual factors in political behavior if the data have

been collected in a hierarchical manner with respondents grouped into

lower-level and higher-level districts.�

The World Values Survey data� (collected in three waves from 1980 to

1997) for 65 countries are ideally suited to examination of the hypothesis that

democratic beliefs and practices are globalizing.� Using three key predictors (trust in fellow

citizens, political interest, and volunteerism) for the sample of 91,160

respondents, it is evident that regional (for the 550 regions) and country

settings (between 55 and 65 countries) are important predictors of political

behavior, on the order of about 10% and 20% respectively.� Respondent characteristics account for about

70% of the variance explained.� Ideology

is far more significant than many of the usual demographic characteristics in

explaining political behavior cross-nationally.�

Dramatic differences between established and new democracies clarify the

political globalization process and global regions (

Using data from 1946-1994 and a measure of democracy

based on political authority characteristics,�

democratization has proceeded in regular spatial and temporal diffusion

patterns and distinct regional trends can also be observed (O�Loughlin et al.,

1998).� Unlike the temporal diffusion

suggested by

����������� The reversal to authoritarianism

anticipated by

Location and Context in Global Political Change

�

Recognition of

the importance of location as a factor in political developments continues to

grow.� First, being part of the same

region or sharing a border with a state undergoing profound political change

increases the chances of political transformations in neighboring countries (Kopstein and O�Reilly, 2000; O�Loughlin, 2002).� Examples from sub-Saharan

A third trend parallels the methodological gap in political science

between the comparativists, who tend to study one

polity or examine a small set of countries, and the macro-structuralists,

who engage in cross-sectional analysis of the countries that constitute the

world system; their separate approaches do not really encourage a rapprochement

on the basis of the shared interest in regional affairs.� While political scientists increasingly

accept and use the geographic techniques of spatial analysis, there is still a

significant knowledge lag between the disciplines about concepts of space and

place.� Most geographers adhere strongly

to notions of �place� as complex areal units that are

shaped by human behavior, beliefs and values over a long period of time (

For the past two decades, geographers have manipulated aggregate data

to demonstrate the small, but statistical significant, effects of the context

in which political acts takes place.� In

almost all instances, empirical analysis examines voting statistics, though

spatial analyses of other kinds of political data such as international

conflict behavior follow the same general modeling procedures (O�Loughlin,

1986; Kirby and Ward, 1987; O�Loughlin and Anselin, 1991).� Important extensions in the spatial analysis

tool set in the 1980s and the integration of these methods with GIS (Geographic

Information Science) visualization techniques allowed geographers to show how

the usual regression equations of aggregate data were probably incorrect �

biased and inefficient estimators and significant clustering (dependence) in

the residuals � and that these kinds of aggregate data required the application

of the specialized tools of spatial analysis.�

MacAllister (1987) and King (1996, 1997)

argued that adding the right kind of predictor variables, fitting the right

kind of model (perhaps log-linear), avoiding the ecological fallacy, collecting

the right kind of information to answer a specific question, or analyzing at

the right scale (more localized analyses) will see the evaporation of the

�geographic factor�.� Geographers,

especially

In recent years, geographers have increasingly turned to survey data

for individuals to report the existence of small but significant contextual

effects in political behavior and attitudes.�

Pattie and

Like other social scientists, geographers are beginning to move from

a �dummy variable� to a multilevel modeling approach for individual level data. �If more than a few regions exist, use of the

dummy variables becomes cumbersome and worse yet, the

nuances of place are poorly captured.�

Alternatively, one could fit the same model for different scales

(individual, regional, national) if the requisite data were available but

cross-scale effects are hidden in this approach.� In multilevel modeling, on the other hand, a

single regression model handles the micro-scale (individuals), the meso-scale (regions or towns) and the macro-scale (states

or countries).�� Moreover, multilevel

models allow relationships to vary according to geographic context, thus

speaking to the heart of the division that separates geographers and political

scientists.� Widely used in public health

studies and educational research to determine the separate and interactive

effects of the characteristics of people and their contextual settings

(communities and schools), multilevel modeling is rapidly growing in use in all

the other social sciences. With both the availability of specialized computer

software and the growing recognition that many models are too general (fit for

aggregate data across the varied contexts within a study site) or too specific

(targeted to the characteristics of individuals with no attention to their

environments), multilevel modeling can be expected to gain more adherents

quickly.��

Jones and Duncan (1996) provide a list of contextual analyses that

can be accommodated within the multilevel framework.� Consider the topic of this chapter, the

explanation of the variation in democratic beliefs, measured by answers to the

question of whether the respondent thinks that democracy is the best political

system.� First, multilevel modeling can

detect and measure contextual differences by considering simultaneously

personal attributes (the micro-scale) and the macro-scale of the country where the respondents

live.� Second, place heterogeneity can be

measured so that we can see how different factors are related to democratic

beliefs across the countries.� Third,

perhaps the greatest potential of multilevel modeling is to take the

interaction of place and individual socio-demographic attributes into

account.� A respondent may answer quite

differently about democracy depending on the ideology or government style of

the country in which he/she is a citizen.�

Whether through intimidation, pressure or conversion, ethnic or� class determinants

of political attitudes can take on different dimensions in different

countries.� Fourth, multilevel modeling

does not assume that all voters of a particular class or other socio-economic

group behave in the same manner.�

Individual heterogeneity is also determined and measured.� Fifth, panel data of a longitudinal nature

(same respondents at different times) can be modeled in a multilevel fashion so

that each wave can be considered as a separate scale and the effects of

changing context over time also measured.�

Sixth, since it is probable based on previous research that voters have

multiple contextual influences (home, work, church, neighborhood),

multilevel modeling allows the measurement of these separate environments.� While all of these different modeling

strategies can be accomplished using familiar multiple regression procedures,

the adaptations to achieve them are cumbersome and require the use of multiple

dummy predictors and a large number of terms in the equation.�

����������� Democracy and Political Values in a

Globalized World

A truism highlights two contradictory trends that characterize contemporary citizens.� Across the globe, growing numbers of people express support for democracy as a value system while in the longest-established democracies, more citizens than ever are dissatisfied with democratic procedures and especially, with the performance of governmental regimes at all levels (Nye, Zellikov and King, 1997; Dalton, 1999; Pharr and Putnam, 2000).�� Even in the new democracies (established after 1989), citizens are increasingly critical of their governments� performances and while not taking to the streets to protest their dissatisfaction, they nevertheless are becoming �critical citizens� like their Western counterparts (Norris, 1999b).� The most vulnerable democracies (candidates for a reversal to authoritarianism after Huntington�s Third Wave) are those that are labeled �partly free� in the Freedom House lexicon, as they seem to be plagued with ethnic tensions, regional and religious polarizations, administrative corruption, controlled elections and weak mass media,� partly-functioning or brow-beaten legislatures, and un-consolidated party systems.� These �democracies� are in danger of not consolidating the gains of the 1980s and 1990s.

����������� In a major project to ascertain the state of democratic values world-wide, Norris and her colleagues derive three main conclusions from numerous studies of a wide range of democracies � a) political support is not one type and needs to be disaggregated into its different components, b) growing numbers of citizens are critical of government performance in rich countries and established democracies, and c) there is a growing tension everywhere between democratic ideals and reality.� The worry for promoters of democracy is that if support for democratic institutions is falling, then support for democratic values can also be jeopardized (Norris, 1999c, 26).� The terms �critical citizens� or �dissatisfied democrats� well describe the current state of play.� Explaining the variation in institutional confidence is not simple, with only a few variables (at the individual level) significantly related to it.� Conventional democratic participation (voting, volunteerism, etc), political attitudes, and national context explain some of the variation but there is only a weak correlation between institutional confidence and protest potential (Inglehart, 1999).

�The national context variable appears consistently as an important factor in setting the nature of democratic values leading Inglehart (1999, 266) to conclude that �we strongly suspect that a supportive political culture is necessary for democratic consolidation but the exact weight to be given to it is a matter of debate.�� Inglehart and his associates have tracked the rise of a change in social values that they call �post materialism� in many countries for over 30 years.� Though there is a correlation between materialist � post-materialist value ratios and economic fluctuations, the noteworthy trend is an inexorable rise in post-materialism in rich countries, a strengthening of materialist values in poor countries, and a generational change toward post-materialist values.� As the public favors more public voice in governmental decisions (part of a democratic culture�s expectations) due to rising levels of education, democratic institutions must adapt to these expectations or come under increased questioning by citizens.� The long-term prospect anticipates mass publics becoming increasingly supportive of democratic institutions as more countries become richer � though established democracies will have to be careful in how they respond to their citizenry (Abramson and Inglehart, 1995; Inglehart, 1997, 1999).

����������� Generalized conclusions about democratic values, institutional performance and post-materialist developments are drawn from cross-national surveys.� In order to make comparative statements, it is first important to establish equivalence in the concepts, terms, phenomena and definitions used in the different national contexts.� In designing the �political values� project, Inglehart (1997, 63) picked a general strategy that designed broadly relevant questions in order to examine to what extent their structure, connotations, demographic correlates, and constraints are cross-culturally similar.�� Factor analysis of the responses to the same survey questions across countries shows that key indicators line up in the same manner in different national settings (Klingenmann, 1999), allowing Inglehart to develop his 12-item post-materialist index.� However, there is no insistence on forcing similar interpretations onto different settings; interpreting results still requires an awareness of the differences in meaning across cultures.� For example, there is a noticeable difference in the meaning of post-materialism between Western and the former socialist countries and between industrial and low-income countries.� As van Deth (1997, 4) notes, �comparative research must start from the axiom that even similar phenomena are never identical.� The question is whether we can restrict the differences between the phenomena to intrinsic, non-relational properties irrelevant to the goals of our research.�

����������� The World Values survey has a twenty-year history, though its antecedents stretch back to the early years of the Eurobarometer surveys in the European Union states.� Three waves of surveys have now been completed (1981-84, 1990-93, and 1995-1997) and the temporal and spatial coverage is very impressive, covering 45% of the world�s population.� The survey relies on national teams but the nature of the voluntaristic group enterprise means that not all survey instruments are identical, not all sampling procedures are the same, and not all surveys are temporally coincident (Inglehart et al, 2000).� Despite these caveats, this enormous data set constitutes the best information for cross-national examination of political, social, cultural, religious, and ideological values and with its ancillary socio-demographic data, allows a check on assumptions about the spread of democratic values, the arrival of global norms to new settings, the regional concentration of cultural affiliations and traditions, the diffusion of post-materialism, the extent of critical citizenship and number of dissatisfied democrats, and the depth of democratic feelings in democracies, old and new, established and transitional.� It is the data set that I choose for the purposes of teasing out the extent to which national and regional contexts play a role in these global developments.� Global trends might be sweeping aside traditional regional and national value systems producing an �international political culture� or conversely, local attachments and historical memories and legacies continue to shape external values to produce a world of cultural mosaics and democratic diversity within political globalization.

The Multilevel Modeling Procedure

As is ordinary least squares regression, multilevel models operate on the principle that each response is a result of systematic components and fluctuations across the levels.� In the language of regression, each model thus has fixed and random parameters (Goldstein, 1995; Hox, 1995).� Critical to the application of multilevel models is a hierarchical data structure.� In this chapter, survey respondents are the first level, embedded in regions at the second level and these regions in turn are nested in countries at the third level; this is the structure of the World Values Survey data.� Minimum requirements of cases apply to each level and a rule of thumb suggests that there should be at least 15-20 cases per unit at the next highest level.� The selection of the World Values data for this study generated 91,196 cases at the first level, 550 regions at the second level and 65 countries at the third level (though the exact number of cases in each model depends on the mix of independent and dependent variables in the equation and their respective missing data values).�� The most common usage of multilevel models has been in educational settings (e.g., how much of a pupil�s test score can be attributed to the pupil�s abilities and how much to the school environment?), public health (e.g., how much of a person�s lifestyle choices such as cigarette smoking can be attributed to the person�s social status and how much to environmental influences in the form of peer pressure and community practices?) and voting behavior (e.g., what is the relative importance of a voter�s socio-demographic characteristics and his/her community setting in determining voting choice?).�

In regression, a key assumption is independence of the

observations.� Fitting an OLS model for individual data in the presence of

autocorrelation within the groups violates one of the assumptions of regression

� independence of the observations. �If the context in which the respondents live

exercises a significant effect on their attitudes, this assumption is

violated.� Ignoring clustering of

individuals will generally cause standard errors of regression coefficients to

be underestimated (elevating the significance of the predictors) when the

variation could be ascribed to chance but in fact, is based on the groups (Kreft and de Leeuw, 1998; Rasbash et al., 2000).�� Conflating the levels of analysis is also

common so that inferences derived from one level are often applied to another,

termed the ecological fallacy.�

Specifically ordering the data in a hierarchical mode allows attention

to the interactive effects between levels and promotes a clear understanding of

where (which level) and how effects are occurring.� In multilevel analysis, the groups (countries

in my case) at the second level are treated as a random sample of the

population of groups.

����������� Building a multilevel model is an

iterative process adding more explanatory variables onto the first model.� Typically, modeling begins by allocating

variance to each of the levels, a purely random effects model.� If we adopted the usual regression approach,

we would fit an explanatory model for each country (with dependent and

independent variables for each respondent), thus yielding 65 separate

equations.� In this procedure, we assume

that each country has different intercept coefficients, β0j and different slope coefficients, β1j.� The random errors εij for each country

are assumed to have a mean of zero and a variance of σj2.� In the multilevel model, however, we

assume that the variance is the same in all countries and specify this common

error variance as σ2.�

The slope and intercept coefficients are

assumed to vary across the countries.�

Stating the assumption in verbal terms, for respondents with the same

class status, a country with a high value of the intercept is predicted to

produce higher democratic values (say, on the question of �do you trust your

fellow citizens?�) than countries with a low value of the intercept.� Further, differences in the slope coefficient

for the independent predictors are interpreted to mean that not all countries

have the same relationship between the outcome (political value) and predictor

variables.� Some countries, perhaps long

term stable democracies, may have a strong effect while others, perhaps former

Communist states in

After

demonstrating these varying effects, the next step in the multilevel modeling

procedure is to introduce explanatory variables at the second level, countries

in this example.� The multilevel modeling

approach has the strong advantage that it allows us to see if political values

are significantly affected by country residence and citizenship � or the

converse, whether a person�s characteristics (education, age, gender, etc) are

all that we need to know in order to account for the variance in political

beliefs.� If countries matter, serious

consideration must then be given to local factors in accounting for the

institution and consolidation of democracy; if countries are unimportant, then

we can anticipate a global spread of democratic beliefs (and practices) as

income and educational gains diffuse across the globe and international norms

of democracy are adopted without respect to country setting.� In this chapter, a dummy variable that

distinguishes between stable democracies (over 20 years democratic) and other

countries provided the only useful distinction at this stage of the analysis.

����������� The

main aim of multilevel modeling is to separate and measure fixed and random

effects.� Starting from a simple bivariate regression equation, we can extend it to a

multilevel model.� In the bivariate regression equation, the subscript i refers to the

individual respondent:

����������� yi = β0χ 0

+ β1χ1i� +

εi���������������������������������������������������������������������������������� (1).

This simple model at the

individual-level is referred to as the micro-model and can be fitted for all

countries in the sample with yi denoting a

respondent�s score on a political trust variable, χ1i denoting age (a

typical independent predictor), εi the

individual-level residuals, and χ0 is the

constant.�� The two fixed parameters, β0

(intercept) and β1

(slope

showing the change in political trust with increasing age) are interpreted as

usual.� For multilevel modeling, the random

effects captured in the εi are highly

important and rather than simply allocating them to the �unexplained variance�

category, their values can be used in further modeling.� A more realistic model that does not simply

assume the error terms have a mean of zero and a constant variability can be

developed by allowing the political trust measure to vary from country to

country, at the higher-level (second level) of a macro-model.� Formally,

����������� β0j =� �� β0

+ μj����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� �������� (2)

In equation (2) for the second level, β0j , the average value of the social trust variable in country j, is a function of the country-wide average, β0,� as well as a varying difference μj between each country and the overall countries average.� We can combine equations (1) and (2), the micro- and macro-models to make a two-level mixed model:

����������� yij = β0χ0 + β1χ1ij + (μj + εij)������ ����������������������������������������������������������������������� (3)

with the subscript ij denoting respondent i in country j, and the terms inside the parentheses indicate the random part of

the model.� We make the standard

assumption that they follow a normal distribution so that it is sufficient to

estimate their variances, σ2μ

and σ2ε .�

In this model, the same age-political trust holds for each country (same

slope) but the intercept (β0

+ μj) varies according to country.� A further

extension of the multilevel model allows the slopes to vary between countries

so that the age-trust relationship can take on different forms according to the

national context.� Another two-level

model is needed for this relationship of the form:

����������� βij = β1 + Γj�������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� (4)

where the country

slope term is a global average plus the variation from country to country, Γj.� We can now combine equations

(1), (2) and (4) generates the full fixed and random effects model of the form:

����������� yij = β0χ0

+ β1χ1ij + (Γjχ1ij

+ μj + εij)������ ����������������������������������������������������������� (5)

in which the

slopes and intercepts are allowed to vary.�

In equation (5), six values have to be estimated - the two fixed

coefficients, three variances/covariances at level 2,

and one variance at level 1.� In this

paper, I estimate the values for this general class of model with fixed and

random coefficients with the random terms allowed to vary at any level.� If the variances are small, then political

trust is a function only of age with no contextual effects.� However, anticipating the results presented

below, the variances are of a significant size and the conclusion must be that

a combination of fixed parameters (reflecting the socio-demographic

characteristics of the individuals) and random effects (the contextual and individual

variances) is needed for an adequate explanation of the variation of political

values across the world.

����������� In building a multilevel

model, the usual procedure is to start with a variance components model to

determine if there is any variance in the second and higher levels, in addition

to the variance at the first level (the individual voters).� Should there be no evidence of higher-level

variance, a simple regression model is appropriate since there is no geographic

variance visible.� In the variance components

model, only random parameters are present.�

Depending on the nature of the information available and the quest for

either model building or model testing, fixed parameters are added in a

stepwise manner or all independent predictors are entered simultaneously.� The estimation procedure typically uses an

IGLS (Iterative Generalized Least Squares), a maximum likelihood estimation

procedure.�� In the case where the

intra-unit correlations are small, there is reasonably good agreement between

the multilevel estimates and the OLS ones (Goldstein, 1995, 25).� IGLS starts from initial OLS estimates for

the fixed coefficients and builds upon the residuals from the OLS model.� At each iteration,

the weights are adjusted and changed and the residuals re-used in the next

iteration.� All models were estimated

using the specialized multilevel modeling software, MlwiN

(Rasbash et al., 2000).

Data for

Examining Civic Democracy

The number of countries sampled in the World Values

survey varies from wave to wave and in order to have the most complete global

coverage possible while still maintaining temporal consistency, I opted to

combine information from the last two waves (1990-93 and 1995-1997) in this

study.� Only the most recent information

was taken for each country. For example, since the same questions were asked

for a

����������� Choosing

from among the myriad of questions asked in the cross-national survey, I probed

three different elements of democracy.��

Rather than focusing on formal democratic institutions and norms such as

elections, I opted to examine the �civil basis of democracy�;� what extent are people connected to

fellow citizens, are actively engaged in their communities through volunteerism

and are interested in politics?� I was

motivated by Robert Putnam�s (2000) recent work on the

����������� Trust in

fellow citizens does not correlate well with trust in democratic institutions (

����������� Because

yearly Eurobarometer data from the early 1970s and a recent surge in research

in the former Communist countries and in the

����������� The

first dependent variable measured social trust and was derived from another of

the World Values survey questions (http://wvs.isr.umich.edu/index.html).� �To

construct the binary dependent trust variable, I added the �you have to be very

careful� and the �don�t knows� together.�

The average score for all sample countries was 26.3% trust with a range

from 2.8% in

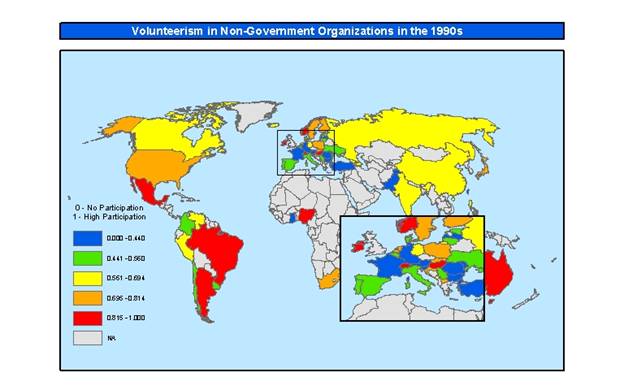

The second variable, volunteerism,

varies dramatically across societies as a result of traditional attitudes,

religious practices, cultural expectations, and recent experiences of

authoritarianism.� The American

democratic model from the early nineteenth-century has promoted civic

engagement in the form of grassroots activism and a strong non-state sector as

antidotes to overweening regime power.�

Since Putnam�s (1993) book on Italian civil society, investigation of

the nature, extent, depth and developments in civic engagement has been carried

out in many of the new democracies, especially in

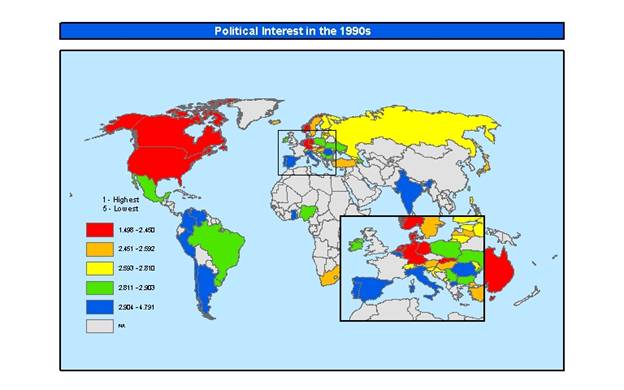

With the rise in �critical

citizenship� in rich countries, interest in formal politics is waning as

attention shifts to more local, grassroots civic activism.� In the former Communist countries, older

people have often experienced four types of regimes, including Nazism and

Communism, and democracy is now evaluated in comparison to these discredited

political alternatives (Mishler and Rose, 2001).� Alienation from the political system is

growing and electoral turnout rates are falling as many regimes are blamed for

declines in living standards. Mishler and Rose

therefore conclude that support for the new democracies is relative and

contingent.� If one only uses electoral

turnout rates as the indicator of political interest, it appears as if the

traditional democracies are unable to engage their citizens in politics and

that the newer democracies are repeating the experience of a long slow steady

decline in electoral participation.� Held

(1993) in Prospects for Democracy asks if democratization is essentially

a Western project or something of wider universal appeal.� As Western democratic societies lose interest

in politics, will other regions follow suit?�

Democracy relies on an active, informed citizenry for its successful

operation.� If political interest

continues to decline as it has in

The organizations for the

volunteerism index are church or religious organization; sport or recreation

organization; art, music or educational organization; labor union; political

party; environmental organization; professional association; charitable

organization; or any other voluntary organization.� To construct the binary dependent variable, I

counted any active membership as volunteerism (respondent answered yes to any

of the organizational membership questions).�

In summary, 61.8% of all respondents stated that they volunteered in

some organization, with a range across countries from a low of 25.1% in

�� �������� The final dependent variable examined

here is political interest.� It is

derived from the answers to the question:�

�Please say, for each of the following, how important is it in your

life� Options for responses were very important, rather important, not very

important, not at all important, and don�t know.� Among the list of interests was �politics�.� In order to form the dummy dependent

variable, I combined �very important� and �rather important� as political

interested and �not very important�, �not at all important� and �don�t know� as

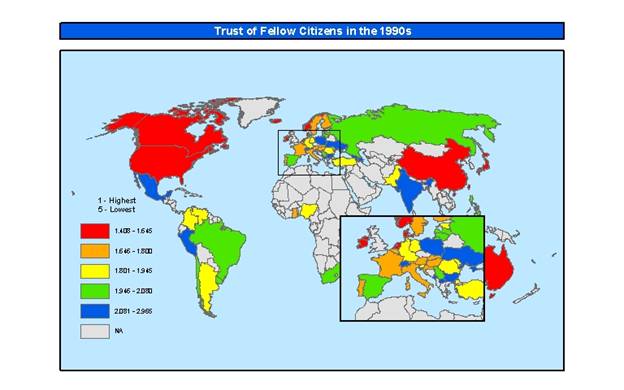

not interested in politics.� Figure 3

shows the average country value for this indicator, with values less than 2.5

indicating high interest.�� Highest

values are seen in

All of the surveys in the World Values project were carried out through face-to-face interviews, with a sampling universe consisting of all adult citizens, aged 18 and over, in the participating countries.� In the usual sampling design, a multi-stage random selection of sampling points within each country was developed with a number of points being drawn from all administrative regional units after stratification by region and degree of urbanization.� In each sampling point, a starting point address was drawn at random.� Further addresses were selected by random route procedures.� Some weighting was initiated to account for expected response rates by region, ethnic group and urbanization (see the World Values website http://wvs.isr.umich.edu/index.html for details).

�

The

Political Geography of World Democratic Values

The analyses of the three dependent variables (social trust, volunteerism and political interest) will be reported separately, though it should be remembered that democratic values are rarely so finitely defined and disconnected.� For most individuals and for most societies, scores on the separate democratic values are consistent and overlapping.� I considered� the option of constructing dimensions of democratic values using the individual variables and analyzing the resulting principal components scores.� While attractive in principle,� the interpretation of the multilevel modeling results of these aggregated and complex scores would be difficult.� The option of selecting individual scores carefully to reflect some of the range of democratic values was followed instead.�

The variance components model, the usual starting point for multilevel modeling, is presented in� Table 1.� The fixed parameter for �thin trust� (trust in people) refers to the intercept value (-1.124) and reflects the log-odds of trusting fellow citizens.� When transformed, the odds are .896 of an individual trusting his/her fellow citizens (�Most people can be trusted a lot�).�� All of the random effects for the social trust model are significant indicating that the three levels (individual, region and country) must be considered in the model.�� As might be expected, the variance at the level of the individual is most prominent but that for the country level (third level) is also very important while the regional factor is less so.� Proportionately, without factoring in any independent predictors, it can be stated that about 66% of the total variance is at the individual level, about 9% at the regional level, and about 25% at the country level.� The last component is particularly noteworthy and suggests that use of the World Values data and similar surveys in predictive models without special regard for the national contexts is likely to overstate the nature of the socio-demographic relationships in the equations.� Much of the explanation is incorporated in the grouping of the data into countries and this context needs to be explicitly tallied in any modeling.�� Clearly there are large and significant differences in social trust between the countries in the sample.� Attention to the regional and country residuals will be given after the multilevel modeling is completed.� Though mapping and graphing of the residuals from the variance components model can help in the selection of independent variables, enough is known about the correlates of social trust from the work of Putnam (2000) and Newton (1999; 2001) that we can proceed to the fitting of the models.

Unlike social trust, the variance components model for volunteerism shows no significant coefficient at the regional level (see Table 1) and thus, one can proceed to a model with only two levels, individual and country.� Surprisingly, the variance components suggest that the national level is more important than the individual for this factor � stated another way, the country where a person lives is more important in understanding the variation among individuals in volunteerism than the characteristics of the persons surveyed.� It is evident from the map (Figure 2) that strong national discrepancies in volunteerism exist due to cultural traditions, political regime character, religious affiliations and the strength of the non-governmental sector. The variance components model confirms this and produces the surprising finding that country-level factors are more significant than personal differences.� The intercept (.359) is also significant and when converted from the logit form, shows that the odds of respondents engaging in some volunteerism� as .494 (the binary outcome variable measures any active voluntary membership).�

Table 1:� Variance Components Model for the Trust in

People, Volunteerism and Political Interest

a) Trust

in People

|

|

Parameter |

Estimate |

Standard

Error |

|

Fixed

Parameter |

β1jk |

-1.124 |

.089 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Random

Effects Level |

|

|

|

|

3-

Country |

v1k |

.344 |

.077 |

|

2-

Region |

u1jk |

.141 |

.019 |

|

1-

Respondent |

e0ijk |

1.00 |

.000 |

b)

Volunteerism

|

|

Parameter |

Estimate |

Standard

Error |

|

Fixed

parameter |

β1jk |

0.359 |

.026 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Random

Effects Level |

|

|

|

|

3-

Country |

v1k |

.999 |

.091 |

|

2 �

Region |

u1jk |

.000 |

.000 |

|

1 �

Respondent |

e0ijk |

.793 |

.020 |

c)

Political Interest

|

|

Parameter |

Estimate |

Standard

Error |

|

Fixed

parameter |

β1jk |

-0.032 |

.087 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Random

Effects Level |

|

|

|

|

3-

Country |

v1k |

0.238 |

.020 |

|

2 �

Region |

u1jk |

0.137 |

.020 |

|

1 �

Respondent |

e0ijk |

0.934 |

.010 |

����������� The final variance components model for political interest shows, unsurprisingly, that the odds of political interest are small.� When the fixed component (-.032) is converted from its logit form, the proportion of respondents showing political interest is only .225.� Since the question was asked in combination with a range of other possibilities in the social and cultural sphere, this low value is not too surprising � and again the map (Figure 3) and summary statistics show a large range in political interest between states.� The variances of the random terms are all highly significant and suggest a three level model.� Proportionately, 71% of the variance is attributed to the individual level, 10% to the regional level, and the remainder (19%) to the country level.� For most democratic and social values, one might expect these sorts of ratios. About two-thirds to three-quarters of the variance is attributed to individuals and the remainder split between the regional and national levels, with the bulk of this remainder associated with the national contexts.

����������� In modeling the variance of the respective dependent variables (social trust, volunteerism and political interest), I opted to use the predictors that had been found to be related significantly to these sorts of political outcomes, as reported in the book edited by Norris (1999b).� Given the presence of collinearity, I dropped the predictor with the weakest correlations; in general, I was looking for a model that met the theoretical specifications of the democracy literature, was parsimonious (an especially crucial factor in multilevel modeling with many random terms), met the requirements of the multilevel method and reported only significant coefficients.� The results of the final models are presented in Table 2; these models include dummy terms (established and new/non-democracies) for social trust and volunteerism that were included in the model as a result of the patterning in the residuals.� The penultimate models did not have these dummy variables.�

����������� In the

first model for social trust, left-right self-placement on an ideological scale

has a negative coefficient � those self-identified as leftists are less

trusting (Table 2).� Social trust is also

strongly and positively related to life satisfaction, a clear replication of

the

����������� The

results for social trust reported in Table 2 are not surprising given the

extensive previous work on the subject in the

Table 2: Final Multilevel Models for Trust

in People, Volunteerism and Political Interest

a)� Trust in People

|

Variable |

Estimate |

Standard

Error |

|

Fixed Terms |

|

|

|

Intercept |

-.565 |

.135 |

|

Left-right

Self Placement |

-0.014 |

.007 |

|

Life

Satisfaction |

.040 |

.006 |

|

Subjective

Social Class |

-0.104 |

.016 |

|

Societal

Change |

-.118 |

.029 |

|

Church

Attendance |

-.036 |

.008 |

|

Est.-New

Democracy |

-.674 |

.183 |

|

|

|

|

|

Random Terms |

|

|

|

3-

Country |

.325 |

.074 |

|

2-

Region |

.147 |

.020 |

|

1-

Respondent |

1.000 |

.000 |

b)

Volunteerism

|

Fixed Terms |

Estimate |

Standard

Error |

|

Intercept |

.415 |

.128 |

|

Life

Satisfaction |

.010 |

.006 |

|

Employment

Status |

.015 |

.006 |

|

Est.-New

Democracy |

-.537 |

.271 |

|

|

|

|

|

Random Terms |

|

|

|

3-

Country |

.914 |

.177 |

|

1-

Respondent |

1.00 |

.00 |

c)

Political Interest

|

Fixed Terms |

Estimate |

Standard

Error |

|

Intercept |

..244 |

.155 |

|

Material/Post

Materialist |

.236 |

.026 |

|

Subjective

Social Class |

-.179 |

.018 |

|

Gender |

-.436 |

.030 |

|

Democracy

Indecisive |

.137 |

.019 |

|

Marital

Status |

-.019 |

.007 |

|

Age |

.013 |

.001 |

|

Societal

Change Direction |

-.162 |

.028 |

|

|

|

|

|

Random Terms |

|

|

|

3-

Country |

.245 |

.056 |

|

2-Region |

.126 |

.019 |

|

1-

Respondent |

1.000 |

.000 |

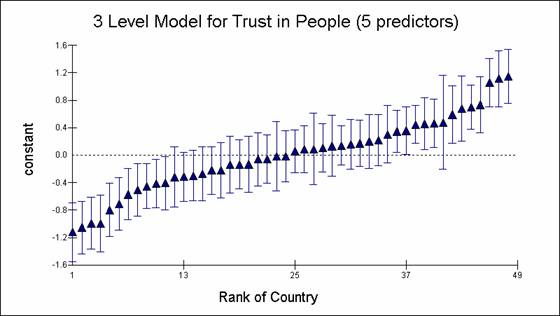

In the final model for social

trust, the intercept value (-.565), converted to an odds ratio, yields an

average level of trust by the stereotypical individual of .633.� More importantly, there is a large and

significant variation across countries.�

Examining the �caterpillar plot� of the residuals from the penultimate

model (same as the final model but missing the democracy dummy variable) shows

the clear trend.� In Figure 4, the

confidence interval bands that do not intersect the mean value (horizontal line

at 0.0) show countries where social trust is significantly over � or

under-predicted.� Eleven countries show

significant average under-prediction (more trust than would be expected on the

basis of the predictors) whilst another eleven show significant over-prediction

(less trust than would be expected).� In

rank-order, the under-predicted values are for

As noted earlier, the final multilevel model for

volunteerism did not require the inclusion of a second-level coefficient for

region and therefore, a two level model (individual and country) is presented

in Table 2.� The intercept value (.415)

translates into a volunteering odd-ratio of .534 for individuals (active in any

organization).�� With the introduction of

the fixed terms in the model, the contribution of the random terms to the

variance is about equal (.914 and 1.0).�

But as noted above, there are dramatic country to country differences in

this ratio of volunteerism.� Volunteerism

at the individual level was significantly related only to two predictors; those

who have a greater life satisfaction volunteer more, as do those with a higher

employment status.� These relationships

are not surprising since it is expected that volunteerism would be higher for

those with the time and the means to take part in such activism.� Putnam (2000) has noted this phenomenon in

the

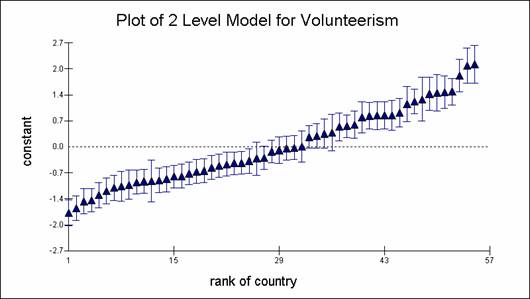

Twenty-five residuals on the over-predicted end of the

rank-order and twenty-two on the under-predicted end of the graph do not have

confidence limits that overlap 0.0. (Figure 5).�� The wider range of values and the increase

in the number of significant residuals is unsurprising given the nature of the

model - The most over-predicted country is Slovenia, followed in order by

Moldova, Bulgaria, Turkey, Austria, West Germany, France, Taiwan, Georgia,

Latvia, Estonia, Bosnia, Chile, Lithuania, Colombia, Ukraine, Uruguay and

Serbia.� At the other end of the

rank-order (volunteerism higher than expected on the basis of the two

predictors) is Argentina, followed by Norway, Mexico, Australia, Brazil,

Hungary, Northern Ireland, Nigeria, Poland, United States, Netherlands,

Macedonia, Ireland, Puerto Rico, Finland, Croatia, South Africa, and

Sweden.�� The residual pattern for the 57

countries in the analysis, while generally conforming to expectations, offers a

few surprises.�

����������� The final multilevel model was also

the most complex with seven independent predictors included in the equation

(Table 2).� Many of the relationships are

relatively weak, though significant.� The

log-odds ratio of political interest, .415, derived from the transformation of

the intercept value (.244) is small; this may be attributed to the nature of

the question which posed political interest against a range of other interests

of the individuals surveyed.� Higher

political interest was expressed by individuals with a more post-materialist

orientation (using the 12 point scale of Inglehart,

2000), by individuals with a (subjective) higher social class, by men, by those

who disagree with the statement that democracy is indecisive, by married

individuals, by older voters, and by those who believe that a change in the

societal direction is needed (Table 2).�

There are no surprises in this list. Once again, interest in the

functioning of a democracy is expressed by those with the time, inclination (as

a result of social status) and resources to pay attention to politics.� As is clear from surveys in former Communist

countries, political interest is strongly related to personal resources.� In

a time of stress, those caught by the changing nature of economic life are

unable to take part.�

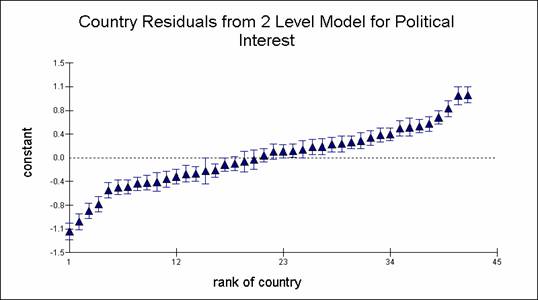

����������� Unlike the other two models, the

display of the residuals did not help to clarify the regional or country aggregations

of over- and under-prediction (Figure 6).�

In contrast to the previous two displays, the confidence intervals are

narrow; fourteen countries have significant positive values (under-prediction)

and seventeen have significant negative values (over-prediction).� The rank order (highest

over-prediction) runs from

����������� This multilevel

analysis has indicated a range of geographic effects.� In all three models, the national context is

an important presence in determining the outcome of democratic opinions on

social trust, volunteerism and political interest.� In two of the three models (for social trust

and political interest), the regional level had a significant presence and

required the estimation of three level models.�

Part of the explanation of the varying presence of region as a factor

could be due to the inconsistent definition of region in the World Values

survey.� Region size is highly variable

from country to country (ranging from the nine large Census regions in the

����������� The compositional correlates of political attitudes were consistent with previous studies and offered no surprises.� What is most impressive from the multilevel model fitting is the residual pattern for countries� that seems to have taken on a macro-regional form on a global basis and also one that corresponds to the disparity between old and new democracies.�� While the pattern in the residuals can be explained by the addition of a dummy variable separating states into these two types, it is entirely possible that further addition of explanatory variables at the country level will assist in accounting for any remaining variance.� Since the main purpose of this paper was to establish the nature of the geographic effects in the distribution of democratic values, this further analysis is left for a later paper.

Conclusions

Geographers have insisted for over three decades that the patterning or spatial autocorrelation visible in the distribution of political phenomena cannot be explained away by the distribution of socio-demographic variables or the clustering of individuals of similar socio-demographic character.� Controlling for these compositional effects offers one insight into the �geography� that remains but a better alternative is to directly model the spatial element.� Multilevel modeling offers a compromise between the usual alternatives, blending individual and aggregate data and allowing a consideration of the multi-scalar effects rather than separate consideration of geographic effects at different scales.� Since most social scientific data are hierarchically organized in a nested fashion, the multilevel approach is tailor-made for modeling this type of information.

����������� In the case of democratic values, the scant evidence from social science surveys over the past 3 decades is that a diffusion of belief in democratic principles has spread at the same time as the growth in the ratio of �dissatisfied democrats� has been noted (Norris, 1999c).� Public opinion surveys show strong attachment to principles of free expression, civil liberties and political choices in the new democracies, even though many of them have neither little historical memory of such traditions nor much experience of freedom.� Efforts of non-governmental agencies based in Western countries to promote grassroots democracy in the form of non-governmental organizations and advocacy groups for women�s rights, the environment, minority and human rights, and protection of constitutional gains have been evident in the new democracies.� Though their contact with the citizens of the new democracies is relatively small, their efforts are not going unnoticed by the regimes.� By training cadres of educators, it is hoped to spread the notions of Western-style democracies and imbue the newly-democratized societies with the values that have helped to sustain the Western democracies.� Continuous pressure from powerful states and the threat to withhold foreign aid to repressive regimes act as powerful incentives for governments and elites at least to feign democratic credentials.� While the ratios expressing beliefs in democratic values are still relatively small compared to their Western counterparts, they are nevertheless growing and further diffusion might bridge the gap that is currently evident between the West and the rest.� The so-called �democratic deficit� applies not only to the gap between citizens and their governments but also to the disparity between the old and new democracies.��

����������� While there seems to be a growing acceptance of the value of democratic governance and the principles that underlie it across the globe, this study has highlighted the country-specific character of democracy.� The evidence in the multilevel regression equations is strong and consistent that the attitudes of individuals are conditioned by their location � in regions and countries of specific character.� Clear and unambiguous geographic effects in the equations and residuals supports the position of geographers that place matters in the sense that it shapes the local debates and political character and this historical memory remains embedded in the political expressions.� This is not to claim that place effects are unchanging and inviolate; rather, geographers hold that places both shape the attitudes and behavior of their residents and in turn, are shaped by the collective expression of this popular will in a reciprocal manner.� Countries or nation-states as they are frequently mislabeled are the most powerful territorial expression and their power to shape identity and political behavior remains unparalleled, despite claims of the demise of the state in a globalized world.�� A full account of citizen preferences, practices and values requires not only knowledge of the compositional characteristics of the individual but also one further characteristic � where she or he lives.

�

References

Cited

Abramson,

P. and R. Inglehart (1995) Value Change in Global

Perspective. �

Agnew, J. A. (1996) �Mapping politics: How context

counts in geography.� Political

Geography 15, 129-146.

Agnew, J.A. (2001) Reinventing Geopolitics: Geographies of Modern Statehood.

Anselin, L. (1988) Spatial Econometrics.

Anselin, L. (1998) Spacestat Version 1.90: User�s Guide.

Anderson, L. (ed) (1999) Transitions

to Democracy.�

Bermeo, N.

(1999) Myths of moderation: Confrontation and conflict during democratic

transitions Transitions to Democracy.�

Boeninger, E.

(1997)

Bollen, K.

(1993) Liberal democracy: Validity and method factors in cross-national

measures. American Sociological Review 54, 612-21.

Bratton, M. and N. van der Walle

(1997) Democratic Experiments in

Diamond, L. and J. Linz (1989) Introduction. in L. Diamond, J. Linz and S.M. Lipset (eds) Democracy in Developing Countries.�

Vol. 4:

Goldstein,

H. (1995) Multilevel Statistical Models. 2nd Edition.�

Held, D. (1993) �Democracy:

From city-states to cosmospolitan order. In D. Held (ed) Prospects for Democracy: North, South, East, West.

Hox,

J.J.� (1995) Applied Multilevel Analysis.�

Huber, E., D. Rueschemeyer and J. Stephens (1999) The

paradoxes of contemporary democracy: Formal, participatory and social

dimensions. In L. Anderson (ed) Transitions to

Democracy.�

Inglehart, R. (1997) Modernization

and Post-Modernization.�

Inglehart, R. (1999) Modernization erodes respect for authority

but increases support for democracy. In P. Norris (ed)

Critical Citizens: Global Support for Democratic Government.�

Inglehart, R.

and M. Carballo (1997) Does Latin America exist? (and is there a Confucian culture?): A global analysis of

cross-cultural differences. PS: Political Science and Politics 30,

34-46.

Inglehart, R. (2000) World

Value Surveys and European Values Surveys, 1981-1984, 1990-1993, and 1995-1997.

[Computer file].ICPSR version.

Jones, K. and C. Duncan� (1991) Specifying and Estimating

Multilevel Models for Geographical Research. Geographical Analysis 16, 148-160.

Jones, K. and C. Duncan� (1996) People and places: the Mmultilevel Model as a general famework

for the quantitative analysis of geographical data. In P. Longley and M.Batty (ed) Spatial Analysis in a GIS Environment.�

Joseph,

R. (1997) Democratization in

King,

G. (1996) Why context should not count. Political Geography 15, 159-164.

King,

G. (1997) A Solution to the

Ecological Inference Problem : Reconstructing

Individual Behavior from Aggregate Data.

Kirby,

A. and M.D. Ward (1987) The spatial analysis of peace

and war. Comparative Political Studies

20, 293-313.

Klingenmann, H.-D. (1999) Mapping political support

in the 1990s: Global trends. In P. Norris (ed) Critical

Citizens: Global Support for Democratic Government.�

Kreft,

Lipset, S.M. (1959) Some social

requisites of democracy, economic development and political legitimacy. American

Political Science Review 53, 69-105.

Lipset, S.M. (1994) The social

requisites of democracy revisited. American Sociological Review 59,

1-22.

Lipset, S.M., K.R. Seong and J.C.Torres (1993) A

comparative analysis of the social requisites of democracy. Studies in International

Comparative Development 16: 155-75.

MacAllister,

Mishler, W. and R. Rose (2001) What are

the origins of political trust? Testing institutional and

cultural theories in post-Communist societies. Comparative Political Studies 34, 30-62.

�

Nye,

J.S., P.D. Zellikov and D.C. King (eds) (1997) Why People Don�t

Trust Government.

Norris,

P. (1999a) Conclusions: The growth of critical citizens and its consequences.

In Norris, P. (ed) (1999) Critical Citizens:

Support for Democratic Government.

Norris,

P. (ed) (1999b) Critical Citizens: Support for

Democratic Government.

Norris,

P. (1999c) Introduction: The growth of critical citizens? In Norris, P. (ed) (1999) Critical Citizens: Support for Democratic

Government.

O�Loughlin,

J. (1986) Spatial models of international conflict: Extending theories of war

behavior. Annals, Association of American

Geographers 76, 63-80.

O�Loughlin,

J. (2000) Geography as space and geography as place: The divide between

political science and political geography continues.� Geopolitics

5 (3), 126-137.

O�Loughlin,

J. (2001) Geography and democracy: The spatial diffusion of political and civil

rights. In G.-J. Dijkink and

H. Knippenberg (eds)

The Territorial Factor: Political

Geography in a Globalising World.�

O�Loughlin, J.

(2002) Spatial and quantitative models in political geography.�

In J. Agnew, G. � Tuathail and K. Mitchell (eds) A Reader

in Political Geography.

O�Loughlin,

J. and L. Anselin (1991) Bringing geography back to the study of international

relations: Spatial dependence and regional context in

O�Loughlin,

J. and J.E. Bell (2000) The political geography of

civic engagement in

O�Loughlin,

J. , M.D. Ward et

al. (1998) The diffusion of democracy 1946-1994. Annals of the

Association of American Geographers 88, 545-574.

Pattie,

C. and R.J. Johnston (2000) �People who talk together vote together�: An

exploration of contextual effects in

Putnam,

R. (1993) Making Democracy Work: Civic

Traditions in Modern

Putnam, R. (2000) Bowling

Alone:� The Collapse and Revival of

American Community.

Rasbash, J.

(2000) A User�s Guide to MlwiN.

Rueschemeyer, D., E.H. Stephens and J.D. Stephens (1992) Capitalist Development and Democracy.

Rustow, D.A. (1970) Transitions to

democracy: Toward a dynamic model. Comparative Politics 2, 337-63.

Shin,

M. (2001) The politicization of place in

Tarrow, S. (1996) Making social

science work across space and time: A critical reflection on Robert Putnam�s Making

Democracy Work. American Political Science Review

90, 389-97.

Figure 1: Global Distribution of Trust of Fellow Citizens in the

1990s.� Data are from the World

Values survey questions.� The value for

each country is computed on a 5-point scale from responses to the question �Generally speaking, would you say that most

people can be trusted or that you can't be too careful in dealing with people?�

Figure 2: Volunteerism in Non-Governmental Organizations in the

1990s.� The World Values question

posed for involvement in non-governmental organizations was: �Now I am going to

read off a list of voluntary organizations; for each one, could you tell me

whether you are an active member, an inactive member or not a member of that

type of organization?�.�

Figure 3: Political Interest in

the 1990s.� The index is derived from the World Value

survey answers to the question:� �Please

say, for each of the following, how important is it in your life� Options for

responses were very important, rather important, not very important, not at all

important, and don�t know.� Among the

list of interests was �politics�.

Figure 4: Residuals from the

Final Model for Social Trust (three level� model with� 5 predictors).

Figure 5:� Residuals from the

Two-Level Model of Volunteerism

Figure 6: Residuals from the 2 level model of political interest

[1] �This research was supported by a grant from

the National Science Foundation and was conducted in the context of the

�Globalization and Democracy� graduate training program in the