Please note, the orginal article can be found here.

Geographies of war and peace

A CU professor has spent years studying the aftermath of two war-torn regions: Bosnia and the North Caucasus. He finds geographically varying levels of environmental destruction, forgiveness and repatriation, along with disparate prospects for peace.

By Clint Talbott

The civil war that engulfed Bosnia-Herzegovina has ebbed, but the conflict in the North Caucasus area of Russia still simmers. The conflicts displace people, harm the environment and leave festering wounds.

These effects can be measured and mapped, which can help scholars better understand the consequences and perhaps even help prevent the outbreak of war.

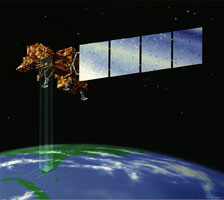

John O’Loughlin, a professor of distinction in geography at the University of Colorado

Political scientists and historians have long analyzed conflicts, but John O’Loughlin, a college professor of distinction in geography at the University of Colorado, views civil war through the lens of his discipline.

With that perspective, O’Loughlin, who is also a research associate at CU’s Institute for Behavioral Science, has revealed much about the aftermath of these violent conflicts: which agricultural land has been abandoned because it is littered with land mines, which communities are (and are not) likely to forgive their former adversaries, where refugees have (and have not) returned to their former homes.

In the 1990s, after the breakup of the former Soviet Union, Bosnia-Herzegovina and the North Caucasus both erupted into civil war.

Having studied these regions with methods ranging from satellite data to public-opinion surveys, O’Loughlin sees differences between the two war-torn areas.

“I’m optimistic in some ways that the conflict in Bosnia will not erupt again,” O’Loughlin says. “By contrast in the Caucasus, I don’t see any end to conflict at all.”

O’Loughlin is the principal investigator of an international team that won a $658,610 National Science Foundation grant in 2004 to study the dynamics of civil-war outcomes in Bosnia and the North Caucasus.

As O’Loughlin notes, the research deepens the empirical analysis of the underlying factors of possible future conflict in the Islamic republics of the North Caucasus of Russia and in Bosnia. “It also gauges the prospects for peaceful relations between nationalities in the two regions and provides answers to key questions about the nature of community conditions in former war zones,” O’Loughlin states.

In a December 2009 special issue of the Annals of the Association of American Geographers—titled “Geographies of Peace and Armed Conflict”—Editor Aubrey Kobayashi of Queen’s University notes that geographers have historically helped nations fight wars.

O’Loughlin is co-author of three papers in this special edition, which Kobayashi says provides “compelling evidence of the ways that geographers can contribute in times of emergency using the very technologies that have been instrumental in waging war for waging peace.”

Lingering tension in Bosnia

The Bosnian war of 1992 to 1995 was notorious for “ethnic cleansing.” Radovan Karadzic, a Bosnian Serb leader, faces charges of genocide, crimes against humanity and crimes perpetrated against civilians and places of worship.

Historically, O’Loughlin notes, Bosnia contained three peoples: Bosnian Muslims (or Bosniaks), Serbs and Croats. The ethnic groups have long borne grudges for atrocities committed during World War II.

“They couldn’t do anything about it during the oppressive Titoist years, but when they got their chance, they took advantage of it,” O’Loughlin notes. (The authoritarian Josip Broz Tito ruled Yugoslavia for three decades after World War II and is credited with holding the country together.)

After his death and the break-up of the Soviet Union, ethnic groups in the former Yugoslavia remembered grievances from six decades ago “as if they happened yesterday,” O’Loughlin says.

All sides committed violence in the 1990s, but the worst was perpetrated by Karadzic’s minions. In 1995, more than 7,000 Muslim boys and men were murdered at Srebrenica; this mass killing came to symbolize the ethnic-cleansing campaign.

The Bosnian war also included systematic campaigns of mass rapes of 20,000 to 50,000 women. All sides committed sexual violence, but most was committed by Serbians against Bosnian Muslims.

An estimated 100,000 Bosnians died during the three-year war, which ended with the Dayton Peace Accords of 1995. That pact guaranteed the right of refugees and “displaced persons” to freely return to their homes, and to be compensated for the loss of any property.

More than half of the pre-war population of 4.4 million was displaced, and more than a million people became refugees.

Of about 1 million people returning, O’Loughlin and fellow researcher Gearóid Ó Tuathail of Virginia Polytechnic and State University found that Serbs were least likely to reclaim their former homes. Only 33 percent of Serbs have claimed their formerly owned homes, as compared to 76 percent of Bosniaks and 87 percent of Croats.

A Bosniak village road sign that has been defaced by Serb nationalists derides them as 'Turks' and indicates lingering ethnic tension.

O’Loughlin sees this as a “clear indication that Bosnian Serbs tend to be more invested in the idea of separate ethno-territorial homelands. His team’s survey also found Serbs less open to a multi-ethnic state than Bosniaks or Bosnian Croats.

The typical returnee in Bosnia, O’Loughlin’s group found, was attached to her or his prewar village and home, was among the poorest in a poor country, suffered from discrimination and was either Bosniak or Bosnian Croat.

Even as they reclaim their former homes, O’Loughlin notes, some returnees are reminded of their second-class status. He cites the “mundane” example of this on a Bosniak village’s road signs; the signs were defaced by Serb nationalists to deride Bosniaks as “Turks,” whom Serbs have traditionally disliked.

O’Loughlin likens this “minor gesture” to transforming neighbors into outsiders, foreigners in their own land. “Bosnia is not yet beyond ethnic cleansing,” he observes.

Deadly fields lie fallow

A sign indicating the presence of a mine field. Such mine fields have significantly reduced the amount of farmable land in Bosnia-Herzegovina.

About 1 million land mines are scattered around Bosnia-Herzegovina, which is the most mine-afflicted nation in Europe. About 1.3 million people live in 1,366 mine-laden communities. Only about 60 percent of the mined areas have been identified.

At the same time, the pace of mine eradication is glacial. Only about 4 percent of the mines laid in the 1990s have been removed. “At present rates of removal, it will take over a century to complete the process,” O’Loughlin writes.

That’s partly because land mines are cheaply deployed but expensively extracted. Planting a land mine can cost from $3 to $10, but removing one can cost 100 times more.

Using satellite data, O’Loughlin’s group aimed to determine to what extent remote-sensing imagery could identify land that had been abandoned because of land mines. Most Bosnians derive their livelihoods from agriculture, so fields of mines instead of crops have a real human impact.

O’Loughlin and Frank D.W. Witmer, a postdoctoral research associate in CU’s geography department, studied data from the Landsat 7 satellite showing the Bosnian landscape before, during and after the war.

Not surprisingly, localities near the front lines and in eastern Bosnia, the locale of intensive fighting, were particularly affected.

O’Loughlin and Witmer used the Landsat data, along with ground-based validation, to establish whether satellite images could help determine which agricultural land is abandoned after a civil war.

Satellites produce images that are used to identify abandoned farm land.

Some of the most fertile land in Bosnia is mined, O’Loughlin notes. As he and his team worked to validate satellite data, they sometimes found themselves on rarely driven, and possibly dangerous, back roads with “grass coming over the hood.”

“In some cases, in hindsight it was really stupid,” O’Loughlin says, noting times he thought, “Why are we driving on this road?”

Satellite images can indeed pinpoint abandoned farm land, they found. However, the technique is much more accurate when used to study areas that have deeper topsoil and more annual rainfall. It is less accurate in areas that are drier and less fecund, the researchers found.

The satellite-monitoring method can be effectively employed in areas with a strong “vegetation signal,” the authors conclude.

But, as O’Loughlin notes, nighttime satellite data can also yield other clues as to land-use changes. “Essentially, the lights go out when people leave a war zone.”

Nascent chaos in the Caucasus

While Bosnia grapples with the post-conflict landscape, the North Caucasus region of Russia is in the midst of continuing, though mostly low-level, conflict.

The North Caucasus consists of six republics: Chechnya, Ingushetia, Dagestan, Kabardino-Balkaria, Karachaevo-Cherkessia and North Ossetia. Along with Kristen M. Bakke of the University of London and Michael D. Ward of Duke University, O’Loughlin used public-opinion surveys (that they contracted to Russian pollsters) to produce the first study that “systematically examines intergroup forgiveness” in the region.

The Caspian Sea provides the backdrop for Derbent, a city of Dagestan. Dagestan is one of the six republics of North Caucasus.

Impediments to forgiveness are significant. By one estimate, there were at least 17 active insurgent groups in the North Caucasus in 2005, when the O’Loughlin team did its survey. These groups are fueled by an abundant supply of weapons, unemployment, radical Islamic groups and religious discrimination, O’Loughlin notes. Most of the violence is directed against Russian political and military targets.

In the past 15 years, conflicts in the North Caucasus have killed between 75,000 and 100,000 people. The most famous incident was the three-day terrorist siege of a school in Beslan, North Ossetia, in 2004. Chechen and Muslim Ingush militants kept more than 1,100 people, including more than 700 children, hostage.

The siege ended with a series of explosions in the school and a firefight between Russian forces and the militants. At least 334 hostages, and 186 children, died.

O’Loughlin says Beslan is “the most horrific place I’ve ever been.” He adds, “It’s pretty easy to get depressed about this. … It was incredible not only that the massacre happened but that the world watched it happen.”

Specifically, the researchers set out to determine if there is a “geography” to reconciliation. They found that there was. As the public-opinion surveys found, Ossetians are less likely to forgive than are other ethnic groups. Also, those living in communities subject to attacks by Russian military and paramilitary forces are less likely to forgive perpetrators, O’Loughlin notes.

“People who lived farther away from the hot spots are generally more leery and suspicious of building cross-community experiences,” O’Loughlin adds.

At the same time, those who feel their lives have been significantly changed by violence are less likely to forgive.

But the North Caucasus is not yet past violence. “Instead, multiple conflicts drag on in many localities, with occasional outbursts of dramatic violence, and their geographies shift from year to year,” O’Loughlin and his colleagues write. After a lull from 2005-2007, the past two years have seen a dramatic upsurge in violence.

O’Loughlin stresses the difficulty of gaining access to the North Caucasus. Research is hindered by cultural and institutional barriers (such as the people’s unfamiliarity with western opinion surveys). And the extensive field work requires difficult and lengthy travel.

Sometimes, O’Loughlin notes, officials will express suspicion about his motivations. His interest, he emphasizes, is purely academic.

“It’s not advocacy work in any way, shape or form,” he says. “We’re not trying to persuade people to behave in any certain way.”